Precision Fire Protection News

Can Solving Data Solve Fire?

Comparing fire data collection from country to country or even between neighboring jurisdictions can produce an array of conflicting variables and definitions. An ambitious new European Union project aims to improve the quality of fire data by finding common ground among member nations, an effort that could become a model for countries around the world.

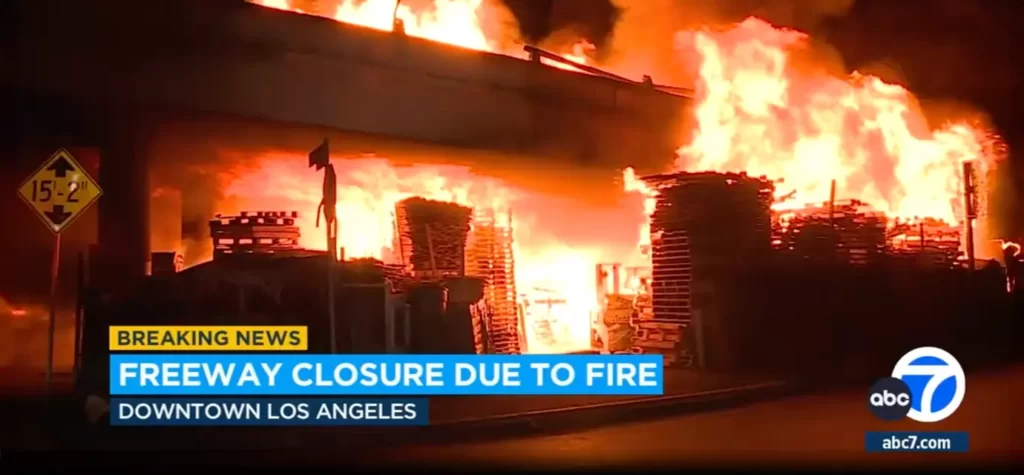

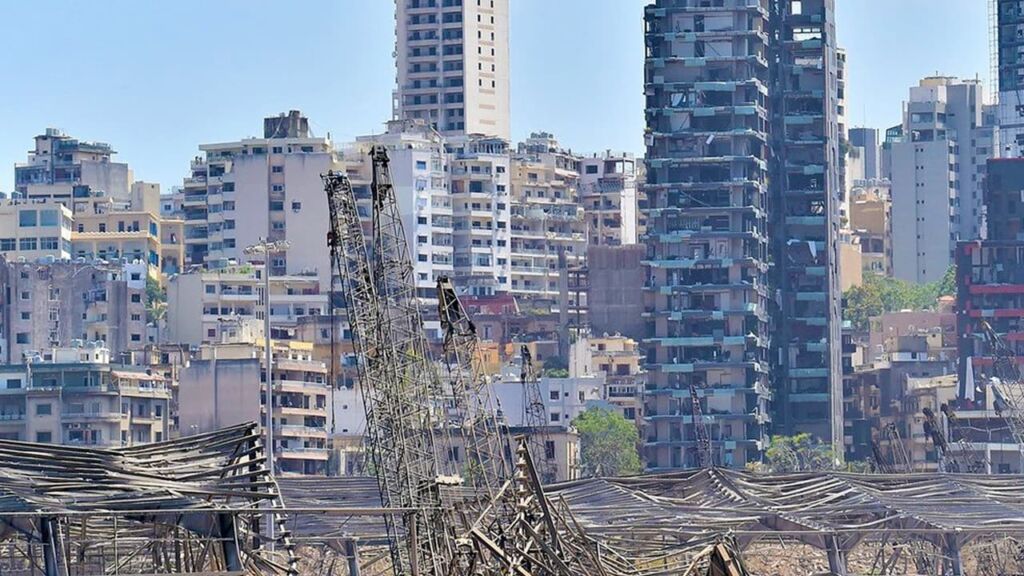

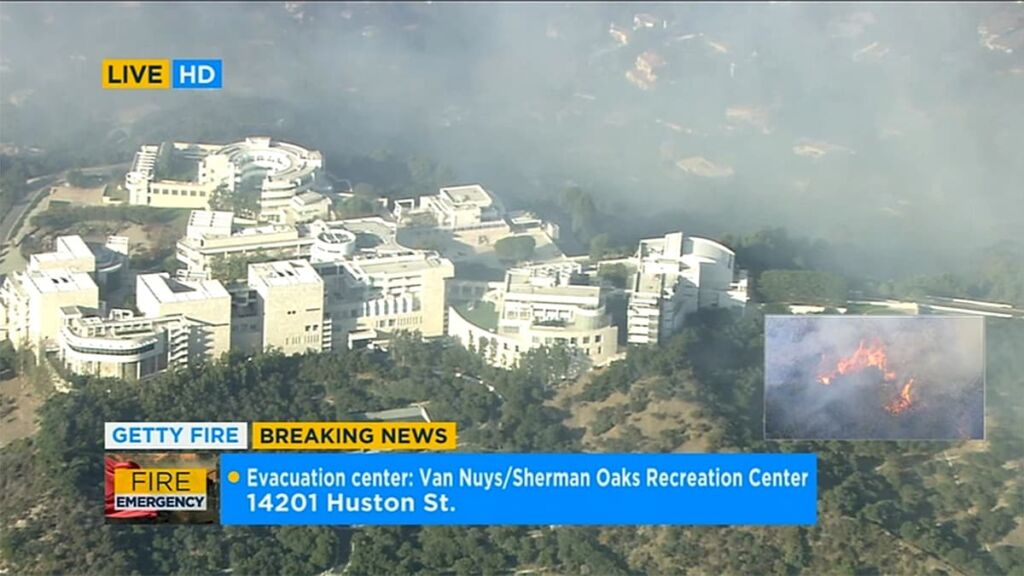

Five years ago, in the months after 72 people were killed in a fire in the Grenfell Tower in West London, citizens and media throughout Europe began raising questions about the effectiveness of fire regulations across the continent. Why was a 24-story apartment building in one of the richest countries in the world not equipped with fire sprinklers? How was Grenfell’s highly combustible façade, which caused a column of flames to quickly ascend and surround the structure, allowed to be installed?

Inquiries were launched. Governments raced to learn how many Grenfell-like buildings existed in their countries. And the European Union Parliament met in Brussels to ask its own broader questions about regulations, strategies, and risks among its 27 member states.

Very quickly, however, officials came up against a hard truth: objectively measuring anything fire-related in Europe was nearly impossible. Despite member nations sharing open borders and political and monetary systems, many vestiges of their pre-EU national bureaucracies remained firmly intact, including wide-ranging differences in how each nation handled the collection and management of national and regional fire data.

From Portugal to Estonia, little to no consistency exists around what data is collected after a fire, whose job it is to collect it, how it is analyzed, and where or if it is reported. “Generally, there is not even consensus between countries in the EU about how to define what a fire incident is,” said Martina Manes, a fire data researcher and professor at the University of Liverpool in England. Under the circumstances, measuring the fire problem across Europe was at best challenging, and effective cooperation around fire policy seemed like a pipe dream.

But the EU also knew it had a problem it couldn’t afford to ignore. Although harmonizing the data collection efforts of 27 nations with 27 unique ways of measuring their fire problems would amount to an unprecedented task, the EU’s unique political arrangement seemed to make it an ideal test case.

In late 2019, the European Commission, part of the EU’s executive branch, issued a proposal for a project it called EU FireStat. It asked a consortium of nine universities and organizations from around the globe, including NFPA, to undertake a massive fact-finding mission to learn what types of fire data each EU country collects and how, and then devise a common system of minimum requirements that could be shared by all.

A report on the ambitious project reveals fascinating insights about the challenges and often maddening complexities of fire data collection. It holds promise, experts believe, not only for the future of fire safety in the EU, but possibly as a blueprint for fire data collection around the world.

“What we have proposed here, any country can take it and implement it. That’s what makes it so cool,” said Birgitte Messerschmidt, the director of research at NFPA and a key contributor to the EU FireStat project.

In June, people gathered at the Grenfell Tower in London on the fifth anniversary of the fire that killed 72 people. Immediately following the fire, nations rushed to determine the extent of their own risk from buildings constructed with combustible exterior cladding, but the lack of similar data made country-to-country comparisons difficult.

Less guesswork, more science

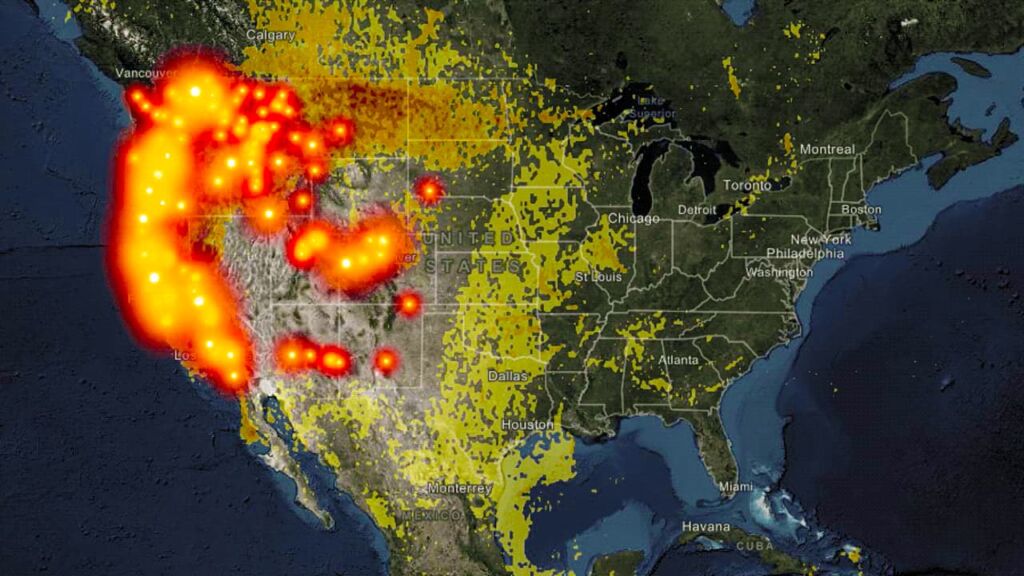

While it’s tempting to regard Europe’s Tower-of-Babel data problem as the exception, the fact is it’s closer to the rule across much of the globe, researchers say. Some countries, like those in Scandinavia, collect vast quantities of data, while many developing nations collect literally nothing at all, a predicament that can leave regulators with significant blind spots. Even when nations or regions do collect the same types of data, definitions of what constitutes a fire injury or death, or even how tall a building is, can vary so drastically that comparisons across borders are meaningless. How can you determine if Serbia or Switzerland has more fire injuries when one counts every scratch, and the other only hospital admissions?

RELATED CONTENT: Quality fire data has already generated an array of important safety steps

These data limitations, which in the past may have been mere inconveniences, are today viewed with great urgency by researchers and officials charged with developing national standards and policies around fire. As the world becomes more connected, more urban, and more globalized, there is perhaps a greater benefit than ever to sharing fire experiences and lessons between countries—and a greater cost for not doing so.

“Local building traditions are fading over time, and the built environment is becoming more similar everywhere,” Messerschmidt said. “The combustible facade fire problem, like what we saw at Grenfell, is a great example. Suddenly, these types of external façade systems are being used all over the world—it’s not just one country having a problem, it’s everywhere. It makes us eager to see data from all over.”

In developing nations, where urban populations are expected to grow by 2.5 billion people over the next 30 years, according to the United Nations, and where funds always seem to be in short supply, targeted solutions driven by data may be even more critical. But these are also the places where fire information tends to be most lacking.

“Getting reliable fire data is a worldwide problem, but especially in developing nations because it is time consuming, it’s expensive, and requires a lot of discipline and cooperation,” said Richard Walls, the head of the Fire Engineering Research Unit at Stellenbosch University in Cape Town, South Africa.

Without accurate information, efforts to make progress on the fire problem are more guesswork than science. There is a greater chance of targeting solutions that don’t work, and of wasting time, money, and resources that could have been devoted to better causes, researchers say. Perhaps worse, insufficient data can lead public officials to vastly underestimate the fire problem, causing either governmental inaction or decisions to divert scarce funds away from fire departments and risk reduction efforts. “The first question is always, ‘Do we understand what’s happening?’” said Walls, who studies the fire problem in Cape Town’s large informal settlements, or shanty towns. “If we cannot even quantify the problem, it’s very hard to try to develop solutions that address it, or to make the case when there are so many other competing priorities.”

Even in countries with relatively robust data gathering efforts, inconsistencies in how data is collected and reported can make the true fire picture elusive. For example, in Johannesburg, South Africa, a city of 5.5 million people, there were fewer than 1,400 fire incidents in 2020, according to official numbers published by the South African government. Cape Town, which has a million fewer residents, had 22,000 recorded fire incidents, according to the government—15 times more than the larger Johannesburg, a difference Walls described as “very unlikely.”

More likely is that Cape Town does a much more thorough job at counting fire incidents than Johannesburg. But Messerschmidt warns that “if the people using the data—whether it’s policymakers, code developers, or even academic analysts—are not aware of some of the challenges during the data collection and reporting phases, it’s easy to draw some very skewed conclusions, and even wrong conclusions.”

The rosy fire picture in Johannesburg, for instance, might lead some policymakers to conclude that budgets for fire departments and fire prevention programs should be slashed to make room for more pressing needs. In Cape Town, officials might decide to devote large sums of money toward trying to emulate Johannesburg’s supposed successes—all based on data that may be telling a lie.

Such a situation puts leaders in a precarious position. “Simply assessing what is working and what is not becomes a huge challenge if you can’t accurately compare experiences between countries or regions,” Messerschmidt said. “If you have strict requirements in one country, how does its fire picture compare to another country with fewer requirements? Can we see a connection? You can’t make those determinations if the data you have is apples to oranges.”

Data deconstruction

Hoping to avoid this fate, the group of researchers tasked with carrying out the FireStat project set to work finding out which EU countries were apples and which were oranges. The job of organizing and managing the work of the nine-organization consortium was awarded to a fire-consulting company called Efectis, and specifically to project manager Mohamad El Houssami. He and the group divided the work into manageable chunks, with the first major task being to survey fire officials in all 27 EU member states to determine what types of data each country was collecting, along with the methodologies used for collecting it.

“For each of the fire data variables countries collected, we also wanted to know whether they had definitions,” explained El Houssami. “For instance, when do you consider it a fire injury? Is it a scratch or something else? Different countries see it differently. The difficulty was finding written definitions—most countries don’t have any, so that is a problem.”

When the consortium members did ask local officials how their system defines a ‘fire death’ or a ‘fire injury,’ some looked confused and said that definitions were unnecessary because the answer is so obvious. “The problem is, in several instances we asked two people from the same agency how they would personally define it, and they had different ideas of what the definition was,” El Houssami said.

At first blush, defining a fire death doesn’t seem to require much thought; either a person died in a fire, or they didn’t. In fact, there are many shades of gray, and depending on how broadly a country defines a death caused by fire, the more deaths will be counted in its national numbers.

“One country might only count a fire death if the victim is found dead in the building. Another might also count it if they died in the ambulance. Some countries also count it if they die from complications a year after the fire. Some count people who die in car fires,” said Messerschmidt, who led NFPA’s involvement with the EU FireStat project. “A weird discussion we had during the project was whether we should count somebody who sets fire to themselves as a fire death or as a suicide. This is why having specific definitions is so important. If everyone is doing their own thing, suddenly you have all kinds of different numbers that aren’t comparable.”

Exploring all of the nuances took project participants down many different rabbit holes. If a building has three stories underground and seven above, does it have 10 stories, or seven? If a person looks injured at a fire scene but refuses care, is that a fire injury? Even deciding what a “fire incident” is can get tricky—is it any incident no matter how we learn of it, or only those where the fire department is called and responds?

Definitions were only the start, however. The FireStat team also wanted to know how data is collected, compiled, and reported, and how countries account for missing data in their models. In the United States, for instance, which only collects data on an estimated 70 percent of known fires, researchers at NFPA fill in the remaining details with estimates based on statistical extrapolation. Countries that mistakenly assume that they are collecting all fires and don’t take that step will end up with a total that is far fewer than the actual number. When comparing apples to apples, it all matters.

“Multiply these challenges by 27 countries and about 20 different languages and you get a sense of the enormity of our task,” El Houssami said.

Instead of apples and oranges, the consortium found something more like a cornucopia that was overflowing with fruits of every shape and size. At one end, countries like Sweden, Finland, and Estonia have robust collection efforts and already collaborate on shared data efforts through an online platform. Other countries, such as Italy, focus instead on collecting a small set of data variables, but do it very well. France, meanwhile, does a good job of collecting fire data, but has very few definitions, so its overall accuracy is suspect.

“Then there are other countries that don’t have any national data collection, or where it’s a completely different situation from one region of the country to another,” El Houssami said. This includes Germany, where each region of the country utilizes a different data collection strategy, and Spain, which has no public system and instead relies almost exclusively on private insurance to collect data. Portugal and some Eastern EU countries have virtually no fire data collection at all, El Houssami said.

As all this was happening, other members in the research consortium examined data collection practices in eight countries outside of the EU—the US, Canada, Norway, Switzerland, Russia, Australia, New Zealand, the UK—to see what lessons might emerge. NFPA worked primarily on preparing information on the US data collection system, known as the National Fire Incident Reporting System, or NFIRS.

Armed with this trove of information, the FireStat group set out to create a data collection system that could serve as a baseline for all of the EU—and, perhaps one day, for countries around the world. In its final report, the group identifies 14 variables “necessary to be collected as a priority in all EU member states in a harmonized way” and includes precise definitions for each. It also offers detailed guidance to officials on each step of the fire data journey, from the data collection process at the departmental level all the way to describing how countries should report their national data to the EU.

While acknowledging its ambitious scope, the report makes clear that achieving its aims will be a long process, and that few countries will be able to meet all of its recommendations right out of the gate. According to FireStat’s research, only seven of the fire data variables it identified as priorities are already collected by more than half of the EU countries. The other seven are currently collected by only a handful of nations and will likely take longer to implement across the continent. Likewise, countries with limited fire data collection efforts will likely need additional money and training, as well as a longer time horizon, before they come up to speed, the report said. Even countries with robust data experience will need time to align their efforts with the report’s new definitions and processes.

“This report is just a beginning,” said El Houssami, who admits that, in many ways, the real work hasn’t even begun. The biggest hurdle will likely be convincing the EU Parliament and the governments of 27 nations to invest the time and money required to realize the vision.

Next steps

Members of the FireStat group will soon meet with EU leadership to present their recommendations and request funding for a pilot project to test how well the FireStat proposal works in the real world. “All of this is very theoretical—even though we tried to make it practical, you always forget something,” El Houssami said. “We need to try and get a couple of counties, regions, or even fire brigades to implement this proposal as a pilot project for a year or two so that we can get data, analyze it, and compare it, which will help us improve the definitions and methodologies of what we’re proposing.”

At this stage, each country’s participation in the project is voluntary, but the hope is that public safety organizations and advocacy groups throughout Europe will see the benefit and put pressure on local governments to join. The early signs are promising. In a survey sent to regulators in each EU member state, all 19 nations that responded said they were in favor of providing harmonized fire statistics for collection at a European level. Before the report was even published, fire authorities in at least a few EU member states discussed changing their data definitions to match those in the report, said Manes, the researcher from Liverpool.

Enthusiasm for the work has been high since the project’s launch. “One of the biggest surprises as we were doing this project was the level of collaboration and the unconditional support that we received from national and local authorities, fire brigades, and the numerous bodies in the EU member states,” Manes said. “There is a high level of interest in improving fire statistics to better understand fire risks and fire protection across the EU.”

Safety experts hope that data harmonization efforts like the EU project can eventually be applied to developing nations, which are home to some of the fastest-growing urban populations in the world, such as Dhaka, Bangladesh (pictured). That population boom will include millions of people at high risk of fire at home and at work—risks that lend an unprecedented urgency to the need for improved fire data collection worldwide.

In the longer term, members of the FireStat consortium believe the model they’ve created could serve as the basis for an international standard on data collection. The last recommendation in the report states that “definitions and methodologies proposed in the project undergo a standardisation process via an official standardisation body which would provide a recognised basis and facilitate its dissemination to all EU member states or even internationally.”

If that were to happen, countries with little to no experience gathering fire data would suddenly have a model that they could follow to help them begin gathering information on their fire problem. In places where data has historically been scarce, having reliable data, even if it’s generated by a few basic metrics, could have a profound impact, researchers say.

“If you’re a fire safety practitioner in these countries, you probably already know this is an issue, but you also have to prove it to the people with the budget,” Walls said. “There are so many competing challenges, whether it’s health care, water supplies, or housing, that the only way to actually get resources is if you can show the size of the problem and that it’s worth investing in.”

In the case of fire data, rising tides really do lift all ships, researchers say. As the world becomes more globalized and the challenges are increasingly shared across borders—from a warming climate to widespread use of battery technologies to building-materials issues like combustible exterior cladding—the more useful global fire data can be to influence policy on a wider scale.

For instance, had some moderate level of international fire data collection been in practice around the world prior to Grenfell, researchers might already have important answers that have eluded us to the cladding problem. Five years later, we still don’t know how many cladding-related structure fires there have been around the world, the circumstances under which they occurred, the characteristics of the buildings, or how many people have been killed and injured. We don’t know exactly what materials the most common combustible facades are made from, or which materials might result in more severe fires. We don’t even know how many high-rise buildings with combustible façades are out there, where they are, or when they were built.

While the EU FireStat project won’t likely change the calculus on cladding, if it is adopted and implemented to its full potential around the world we could be in a much better position to answer the critical fire-safety questions of the future.

“Those who fail to learn from the mistakes of the past are doomed to repeat them,” Messerschmidt said, paraphrasing the philosopher George Santayana. “Data is how we learn from the past. If we do not record these things, if we can’t measure or quantify them, how can we then say if what we are doing is good or bad?”

SOURCE: NFPA

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

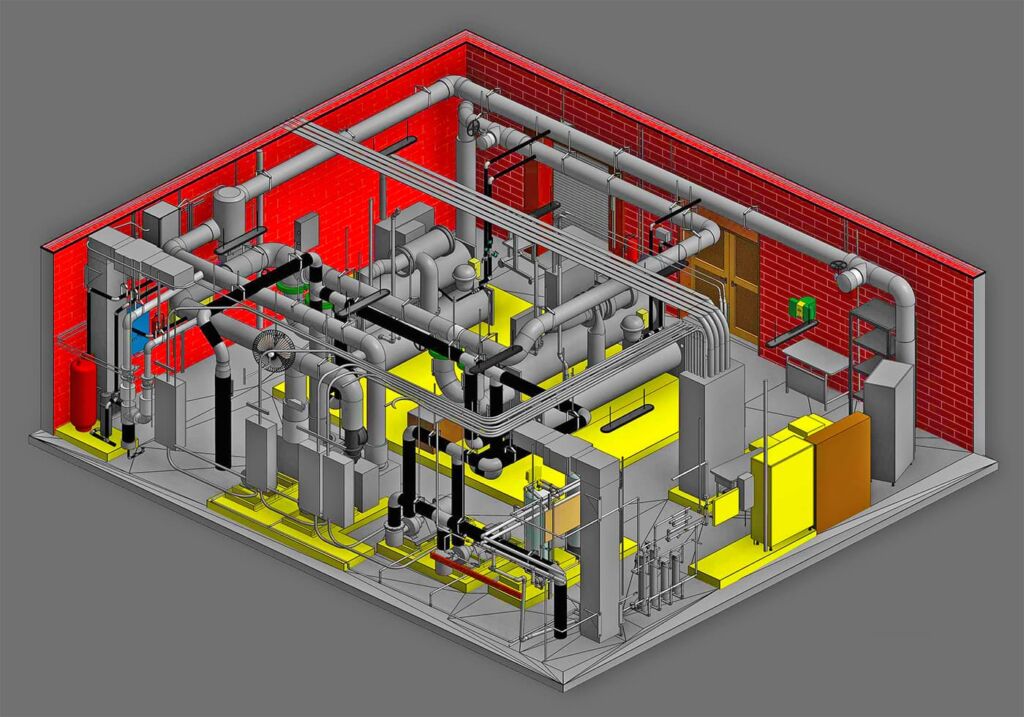

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.