Precision Fire Protection News

Construction Fire Hazards

Construction Fire Hazards

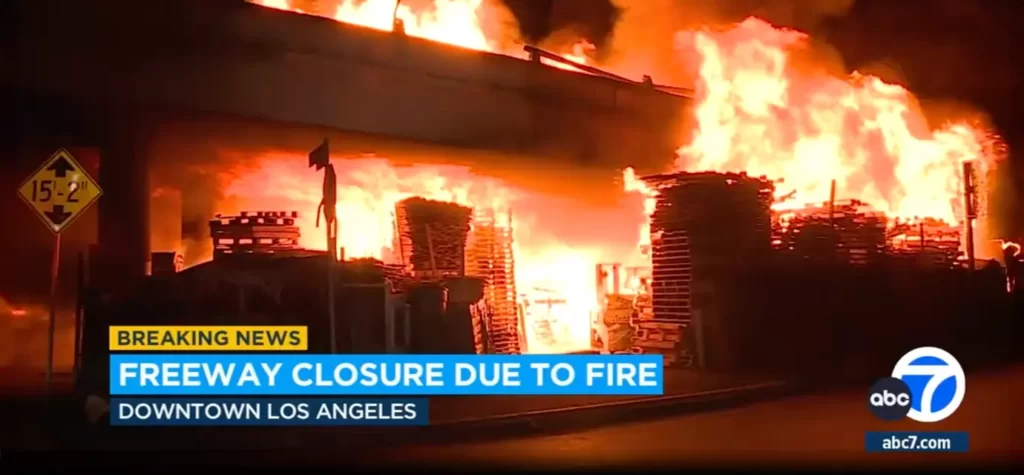

Large and costly fires involving buildings under construction underscores the need for more widespread use of NFPA 241 to address a range of related hazards

BY ANGELO VERZONI

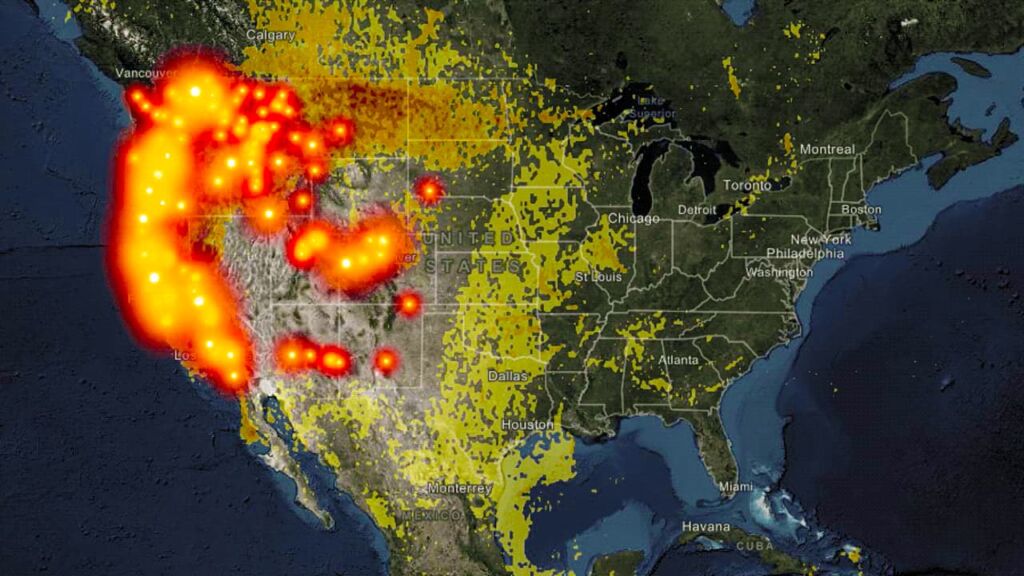

On the evening of August 25, after churning ashore over Southeast Texas, Hurricane Harvey let loose with torrents of rain over the state’s flood-prone coastal plains, the start of a five-day deluge that dumped more than four feet of rain in some areas. Rivers, creeks, and little-noticed irrigation ditches swelled and leapt their banks, spilling into communities from Beaumont to Corpus Christi. Interstate Highway 45, which slices through downtown Houston, was transformed into a slow-moving river. Residents in suburban subdivisions watched helplessly as the water steadily rose, until all that remained were archipelagos of shingled rooftops. It’s estimated that at least 130,000 residences were damaged or destroyed by the flooding, likely leaving thousands without permanent homes for months if not years.

|

As the rain fell in greater Houston, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) ordered its contractors across the country to begin building at least 4,000 new manufactured housing units, the first of which are now being delivered to the region to serve as temporary housing for families in need. Thousands of additional FEMA homes are also expected to be sent to Puerto Rico, where Hurricane Maria wiped out critical infrastructure and left thousands of people homeless.

These new FEMA homes, while not exactly the lap of luxury, are a far cry from the much-ridiculed campers the agency provided to victims of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. While the Katrina campers resemble something you might see hitched to the back of a pickup truck on its way to a campground, the units shipped to Texas are traditional manufactured homes designed for permanent occupancy and fully compliant with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) codes. The homes, which cost an average of about $62,500 to build and $23,000 to install according to a 2016 report, come in one-, two-, or three-bedroom designs to accommodate varying family need. They also include a safety feature few might expect in emergency housing: home fire sprinklers that comply with NFPA 13D, Installation of Sprinkler Systems in One- and Two-Family Dwellings and Manufactured Homes.

“This goes above and beyond the requirements, but it’s what we felt should be done to protect people when they’re most vulnerable—after a disaster, when they’ve lost everything and are in a new home on a temporary basis,” former FEMA director Craig Fugate said in a 2016 video when he introduced the new emergency homes.

The first FEMA homes in Southeast Texas were delivered and installed onsite beginning the second week of October, but it will likely be many more months before all those who qualify have homes. The disaster in Texas marks the second large-scale deployment of these new-generation FEMA sprinklered homes, following the shipment of several thousand units to Louisiana in August 2016. As with Harvey, last year’s Louisiana floods were unprecedented, the result of 31 inches of rain in 72 hours—more than had fallen on Los Angeles over the previous four years. In areas near Baton Rouge, the water nearly reached second-story windowsills, and by the time it receded, as many as 75,000 structures had flooded.

Today, most of the waterlogged debris around Baton Rouge has been hauled away, but signs of the calamity are still apparent a year later, with perhaps the most visible being the more than 4,600 gray FEMA homes still occupying yards and empty lots. In addition to being the primary residences for families who lost everything, the homes are likely the largest collection of sprinklered single-family residences in the region. That will also be the case in Southeast Texas as the FEMA homes continue to arrive.

Most occupants will probably barely notice the presence of the sprinklers, but fire officials don’t mind—they’re just thankful to have one less thing to worry about. “Most fire deaths occur in single-family homes, and the data clearly shows that fire suppression systems like sprinklers save lives,” said Chris Connealy, the Texas fire marshal and a member of the Texas Fire Sprinkler Coalition. “We always appreciate when fire prevention and safety equipment are taken into consideration.”

Complex problem, tight timeframe

How these government-funded temporary emergency dwellings came to have home fire sprinklers was no small feat of engineering—or of political maneuvering. Like many aspects of today’s emergency management planning, the FEMA sprinklers can be traced to Hurricane Katrina.

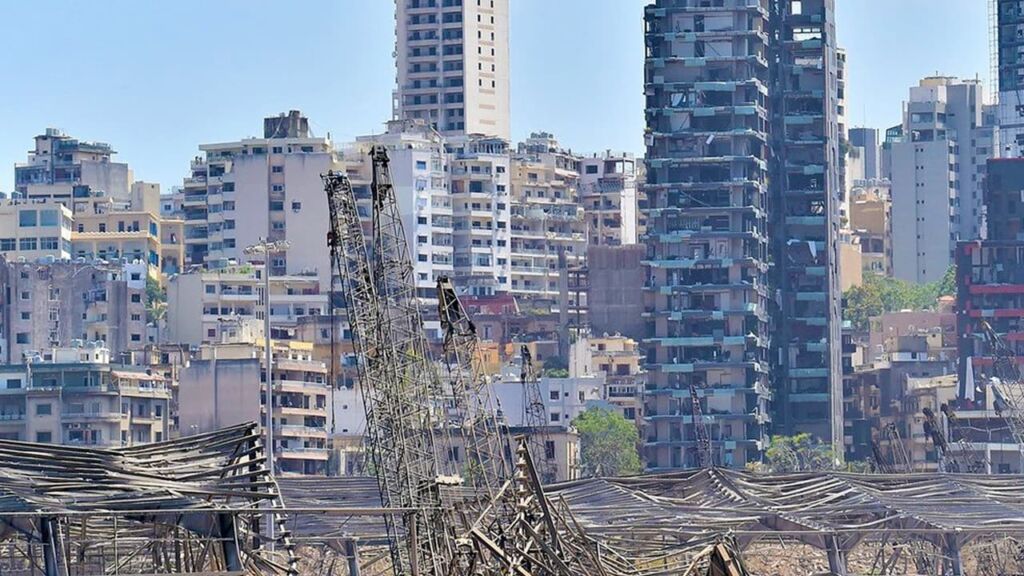

By some estimates Katrina displaced more than a million residents in the gulf region, and while some returned in days, as many as 600,000 people were still homeless a month later. At least 114,000 households turned to FEMA for emergency housing, which hustled to deliver more than 100,000 small campers to the region in what officials believed at the time was a short-term fix to an acute problem.

It didn’t turn out that way. Though well-intentioned, the effort was fraught with missteps, lawsuits, and enduring embarrassments.

Soon after the campers arrived, many occupants began to report headaches and illnesses, maladies later linked to unacceptably high levels of formaldehyde inside certain campers. (In 2012, the companies that manufactured and installed the Katrina campers agreed to pay victims $42.6 million to settle a class-action lawsuit.) Another persistent problem was fire. Several people were killed and many more injured in numerous explosions linked to the camper’s propane tanks, which contractors did not always inspect or install to code.

According to a 2015 letter from FEMA to HUD, FEMA deployed more than 142,000 temporary housing units from 2005 to 2009. “Unfortunately, 186 fires occurred in these deployed units, resulting in 14 deaths and 18 injuries,” the letter states. “FEMA statistics show that the injury and death rates [in those units] have been more than double that of the United States’ manufactured housing in general, and up to double that of other residential experiences.” Due to these and other problems, FEMA suspended use of the travel campers after Katrina and worked to revamp its emergency housing stock. After years of pro-sprinkler lobbying by one of its divisions, the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA), especially by its then-administrator, Ernest Mitchel, FEMA decided in 2015 to go a step further by equipping its stock of new emergency housing with fire sprinklers.

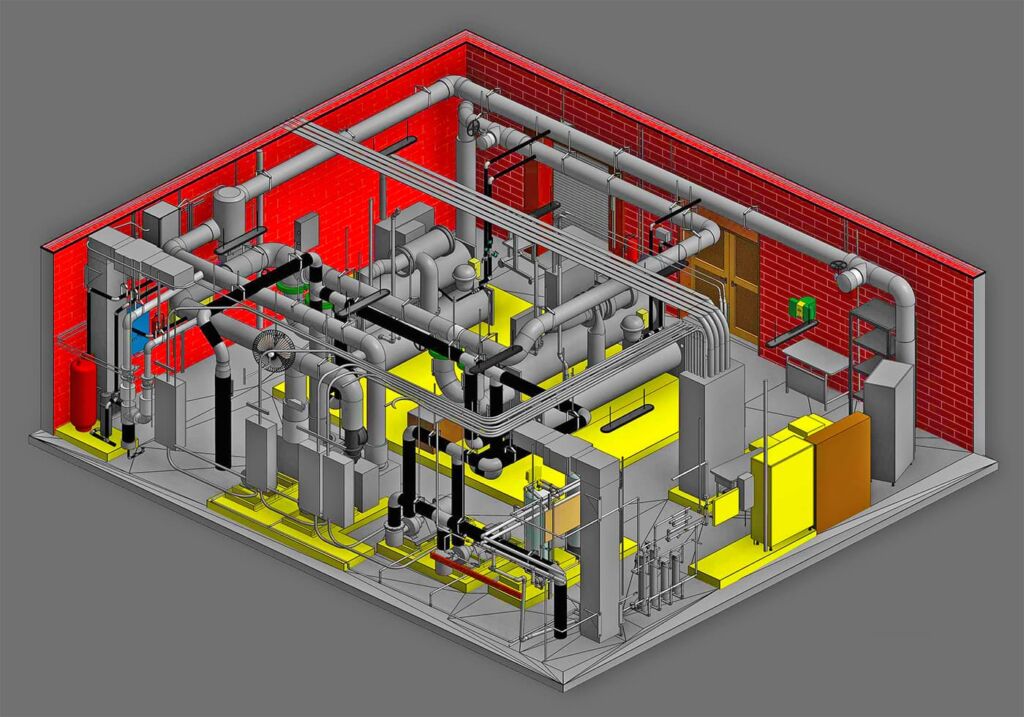

Once the decision was made, USFA officials got to work—and they had a monumental engineering challenge in front of them. “For me, an old grizzled engineer who has had an opportunity to do some really cool things in my career, it was the most challenging project I have ever worked on,” said Lawrence McKenna, Jr., a fire protection engineer at the USFA who was part of the FEMA sprinkler team. “The complexity of it just boggled my mind. I came from the fire protection industry, so I thought, ‘sprinklers in a manufactured home? Boy, that’s a no brainer—that should take me about three hours to install.’ Well, putting sprinklers in one unit is easy. Putting them in 20,000 on a couple weeks’ notice, not knowing where the homes are going to end up, not knowing what the water supply situation is going to be—that’s an entirely different matter.”

The timing of the project was tight, further complicating things. Due to the particulars of an upcoming acquisition contract with FEMA’s manufactured home vendors, the sprinkler system designs had to be delivered in just a handful of months or the whole project would be significantly delayed.

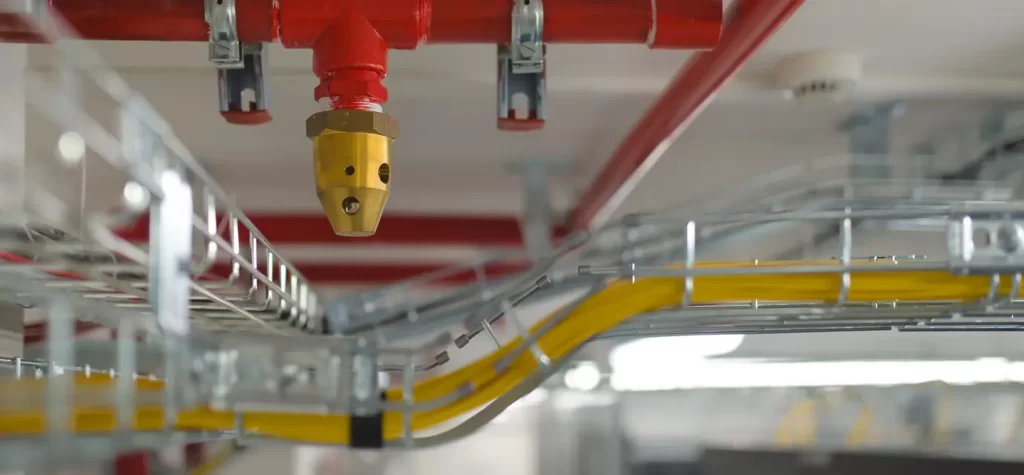

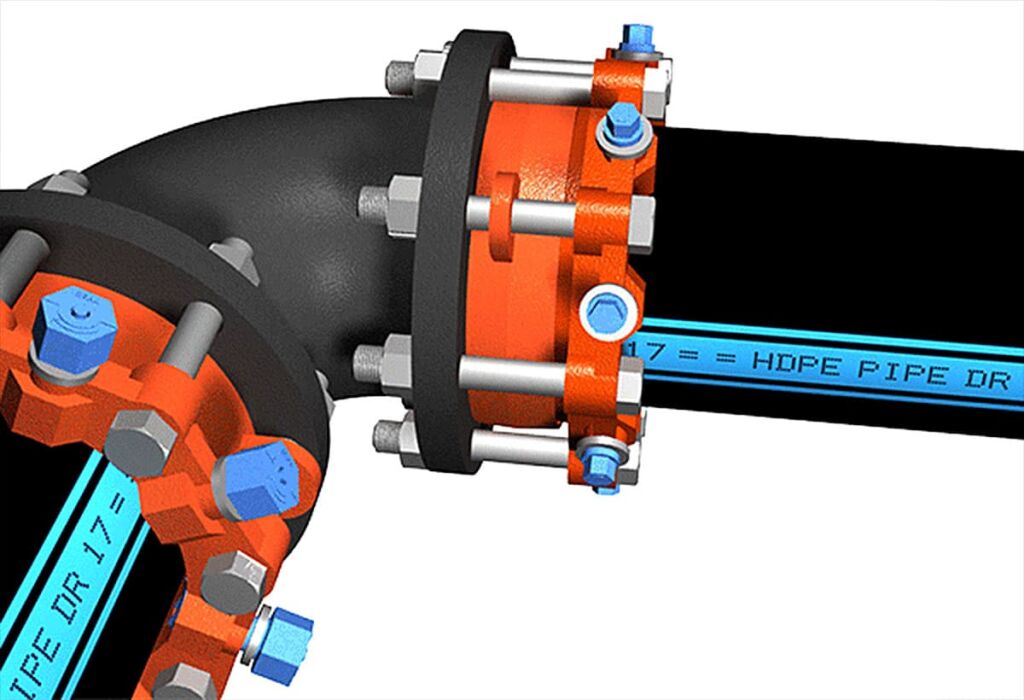

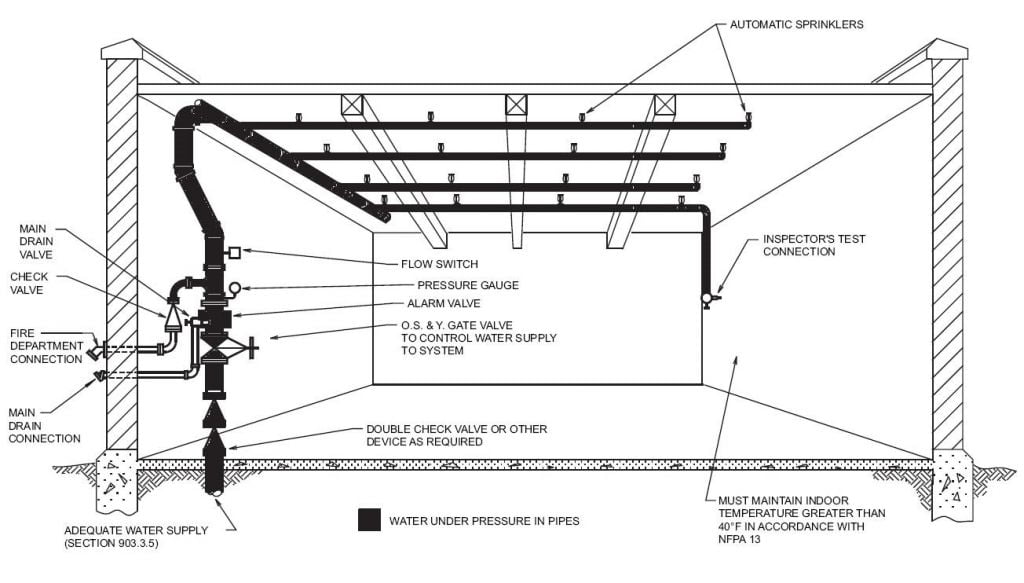

The FEMA sprinkler team began with three baseline needs: the sprinkler system design had to comply with NFPA 13D; the design had to be scalable so that during a disaster like Katrina, FEMA’s manufacturers could crank up production to 50 homes per day and not run out of components; and the system had to work no matter what location it was delivered to or what extreme conditions it encountered upon arrival.

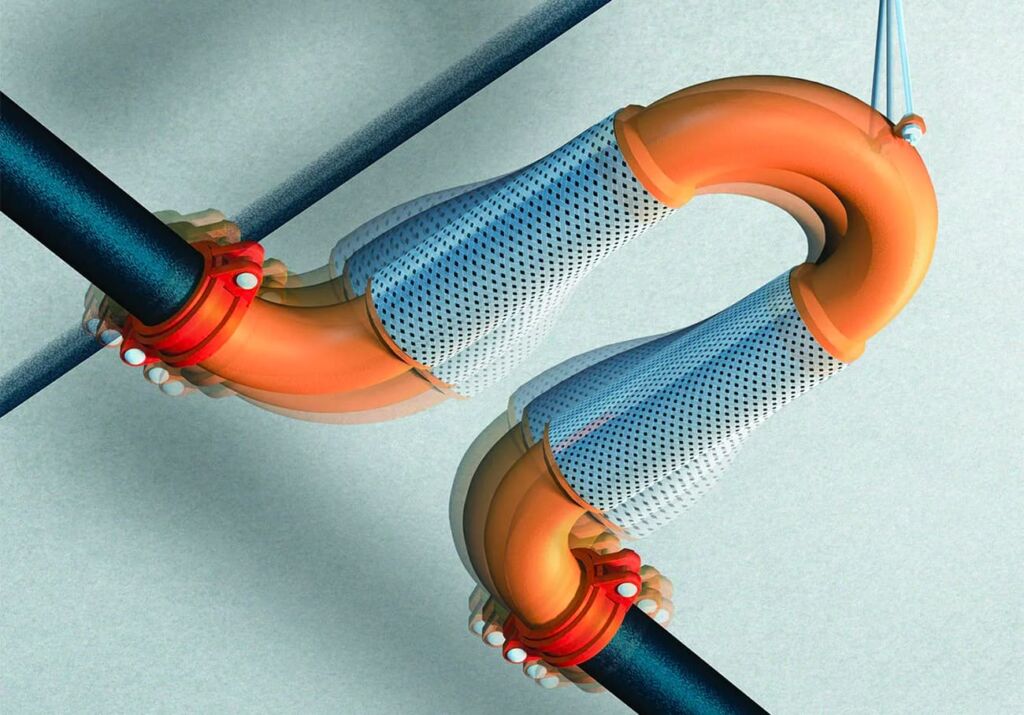

Plug & Play From top, sprinkler system components packed into the water storage tank for transport; sprinklers installed inside a housing unit; and a water storage tank connected to a unit. Photographs: FEMA

The last part was the toughest. Since no one can predict when or where the next disaster might take place, the one-size-fits-all sprinkler system had to be capable of impressive feats of resilience and agility. It needed to function at minus-35-degrees F during the dead of winter in Maine and in the scorching 100-degree-F Arizona summer. It needed to work without guarantee of a reliable water supply onsite, meaning it needed to include its own tank, and it had to be simple enough so that contractors with no experience with residential sprinklers could hook them up onsite. The sprinkler system would also have to potentially survive years of sitting inactive on a FEMA manufactured home storage lot in Alabama or Maryland until it was needed in a disaster. After all of that, it would need to endure perhaps a thousand miles or more of bumps and jostling en route to the disaster site.

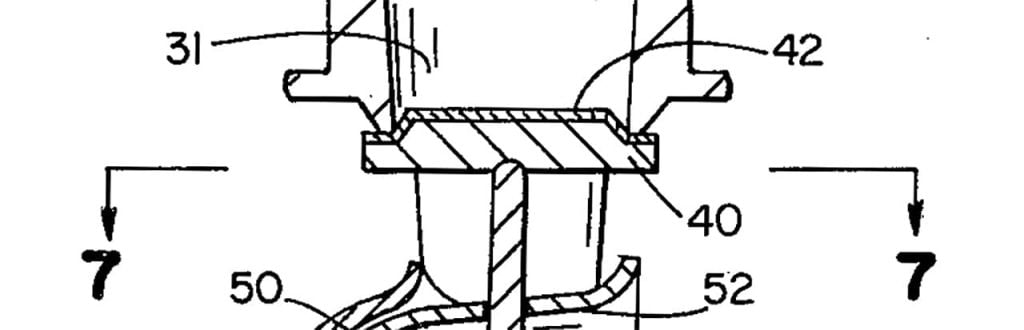

The FEMA team made a list of these variables and set to work engineering solutions to the problems. Some of the solutions were evident from the outset, but the details took a lot of massaging. For one, the team figured that the sprinkler pipes needed to sit within the home’s heated envelope to remove the temperature variables. They first looked at locating pipes above the drywall ceiling under insulation, but that approach was ruled out over concerns that wind gusts while being trailered to a deployment site might blow into the home’s air vents and disrupt the insulation protection. If that happened, the pipes could freeze in cold climates and fail unexpectedly when needed in a fire. Ultimately, the FEMA sprinkler team made the unconventional decision to place the pipes inside the home’s heated living space, along the seam where wall and ceiling meet. To prevent tampering and damage from future occupants, the pipes were concealed under a hard plastic sheath. “I can’t tell you how many ways we looked at hanging the pipe, where to hang pipe, what kind of pipe to use,” McKenna said, adding that the final plan is “maybe not as pretty as we’d like.”

A second hurdle was the unknown onsite water supply. Under the circumstances, FEMA sprinkler team members knew that they needed to use a water tank, one large enough to handle NFPA 13D’s requirements for water flow, which in residences under 2,000 square feet calls for seven minutes of water with two sprinklers activated. The team settled on a 250-gallon tank. However, there was one significant problem: there was nowhere in the home to put the tank. In most residential situations with similar requirements, a tank can be located in the basement or in a closet, neither of which exist in the FEMA homes. Fitting the tank and pump inside the home would have required a significant redesign to the home’s footprint, a change that would have triggered a new contract with manufacturers and a new bidding process. Delays could have stretched for years.

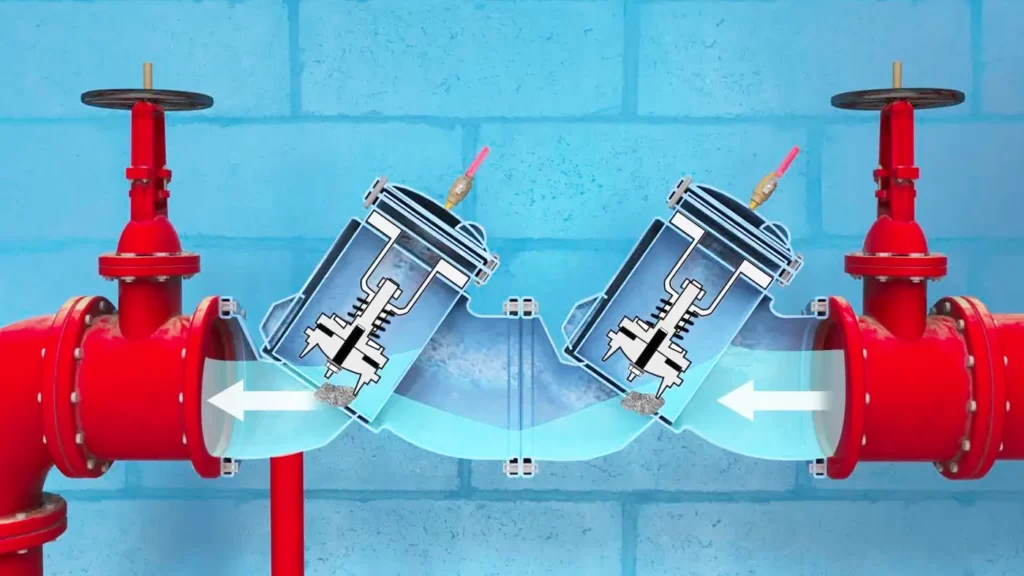

The FEMA sprinkler team concluded that the tank and pump system had to be a separate component outside the home. The team drafted about 20 pages of specifications for the external tank and pump system and asked vendors to design and build something scalable that could work. Three vendors came back with viable options; all are designed uniquely for the project and in use at sprinklered FEMA homes today. While all slightly different, each has the same basic design. The external tank and pump are housed in a heated and insulated box to ensure that the water and components will be functional in case of a fire, whether on the coldest winter night or warmest summer day. A high-strength insulated industrial rubber hose, housed in hard plastic pipe to prevent rodents from gnawing on it, connects the tank and pump to the home via quick-connect couplings. Flow alarms trigger a horn and strobe assembly if the sprinkler system is activated. The tank and pump system also has a maintenance alarm that will go off when the temperature inside the box or hose drops below 40 degrees F.

“The entire tank and pump assembly is designed to be plug and play, because these need to be made operable in the field by plumbers, electricians, and carpenters,” McKenna told a room full of engineers during a presentation on the sprinkler system at the NFPA Conference & Expo in June 2016. “We can’t send a sprinkler fitter into the field for every one of these. The water tank is filled with a water hose during the install and testing, then the system hose is connected and you walk away from it—simple.”

‘Make this thing happen’

Other issues required less dramatic, but equally crucial, solutions. To deal with the pounding the units can be subjected to during transport over thousands of miles of highway, the engineers chose more rugged components than those used in a typical installation. For instance, pipe hangers were ruggedized by requiring anti-chafing features for the CPVC pipe, and they were also spaced much closer together than in traditional installations. In addition, the sprinkler riser, which extends below the floor of the unit, is made of schedule 40 galvanized steel, and is protected against damage from roadway hazards, insects, and other vermin. To address the stresses of sitting in the heat and cold for years before deployment, the team carefully chose specific kinds of sprinkler parts, such as glass bulb sprinklers instead of eutectic metal elements. Research has shown that repeated exposure to high heat can cause chemical changes in eutectic metal alloy that can decrease its melting temperature, McKenna said. “We didn’t want our inspectors to go into the storage lot one day for the monthly inspection and find all the sprinklers popped,” he said. Other parts that could be affected by exposure to heat or cold over time, such as the soldered sprinkler cover plates, are stored in the manufactured home’s refrigerator, where temperatures are more stable, and installed just before the unit is shipped to the deployment site.

While the design was being finalized, FEMA team members in charge of acquisition contacted suppliers to ensure that required parts would be available on a large scale when the next Katrina hit. “We had to get into every single component on these systems to figure out things like how many screws we needed, how many feet of pipe, how many elbows,” McKenna said. “If we have a scenario where we need 50 homes built per day, can the various industries supply that? Can we get 5,000 feet of pipe every week? Turns out we can.”

Another logistical hurdle was squaring the FEMA sprinkler design with the various unique home sprinkler ordinances adopted across the country. While most jurisdictions use NFPA 13D as the basis, many communities amend the code before adoption. As a result, neighboring communities can have slightly different rules. Knowing it would be impossible to comply with every jurisdiction, FEMA staff made a spreadsheet of requirements for every sprinkler ordinance in the nation, and called authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) to run certain requirements and exceptions past them. Every AHJ that FEMA contacted eventually signed off on the sprinkler design. (None of the sprinklered FEMA units in Louisiana or elsewhere have yet experienced a fire that has triggered a sprinkler, according to McKenna.)

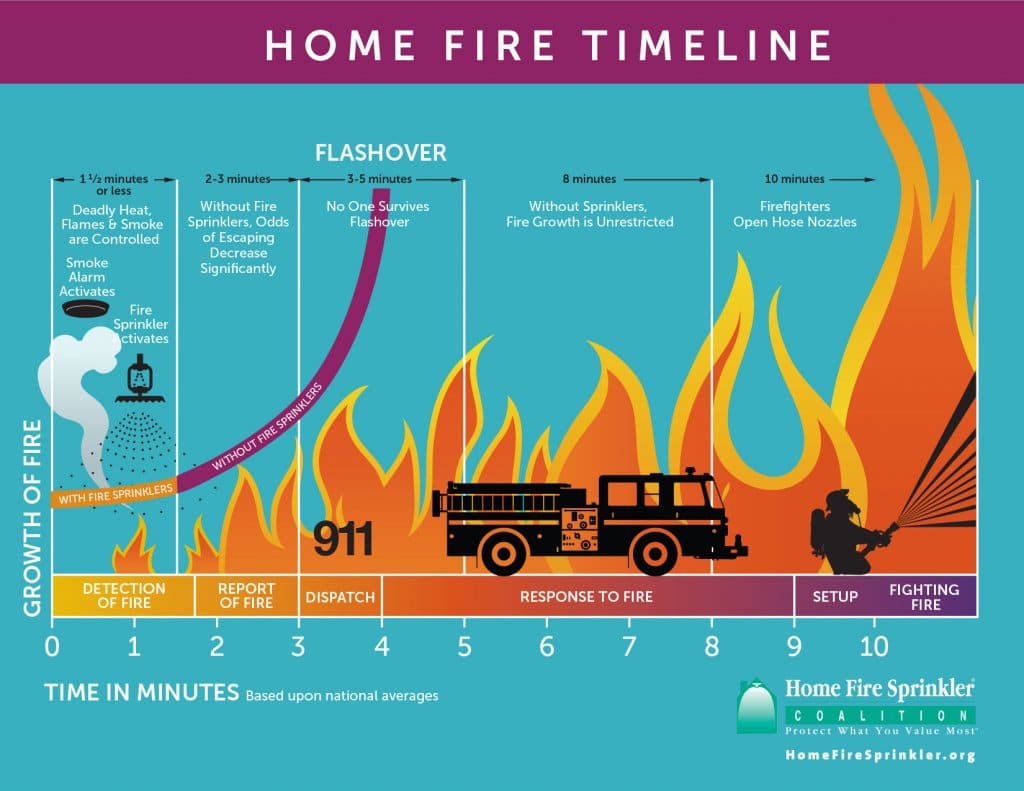

Simultaneously, an opposite but equally pressing practicality was addressed. In jurisdictions without sprinkler ordinances—which are the majority—FEMA knew its units could be the first home fire sprinklers that many building officials, firefighters, and residents had seen. So FEMA crafted educational materials on home sprinklers for local fire departments and municipal officials. The agency also collaborated with the Home Fire Sprinkler Coalition to produce a document for occupants called “Living With Sprinklers” that includes information on sprinkler myths, dos and don’ts, and the unit’s special water tank and pump.

Members of FEMA’s sprinkler team worked nights and weekends to get it done on time, and in September 2015, just nine months after the team had been assigned the task, FEMA took delivery of the first sprinklered unit. “We wanted to make this thing happen while the iron was hot,” McKenna said.

Meeting the emergency need

Almost exactly two years later, Harvey descended on greater Houston, resulting in what is likely the costliest natural disaster in the United States since Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005.

In no time, McKenna said, FEMA had “a gazillion gears all turning at once.” FEMA ordered its manufacturers to build 4,500 more sprinklered housing units in addition to the 1,000 or so it already had in inventory. Days later, FEMA teams headed to the Houston area to look for large empty parking lots or open fields that could serve as adequate staging yards for the units when they arrived. All the while, devastated Texan families began applying for FEMA aid en masse.

As of mid-October, the agency had approved about $1 billion in individual and household assistance for Harvey victims. So far, more than 740,000 households have registered for FEMA aid in nearly 40 Texas counties. Much of the money will go toward housing repairs, and providing temporary housing in the form of hotel rooms or apartments for people who lost their homes and have no other housing alternatives. FEMA is already is paying for tens of thousands of displaced Harvey victims to stay in hotels and motels in 33 states, according to the Associated Press. Administrator Brock Long has reiterated that the manufactured housing option will be a last resort, and that he will work with officials in Texas and Florida to come up with ways to get people back into their homes more quickly without relying on FEMA housing.

“We don’t have enough FEMA units for all the homes that were destroyed,” he said in mid-September at a briefing in Washington. “If you combine Harvey and Irma, this is an extraordinary event that is going to require innovative solutions when it comes to housing.” For thousands of homeless people with uninhabitable homes and limited resources, however, the FEMA homes may be their only viable option.

Getting a family into a FEMA home is not always a short or simple process. Assembling and processing the paperwork to demonstrate need takes time; manufacturers need time to ramp up production of the units, and it takes time for the units to be shipped. When a family is approved and the unit arrives at the staging area, it takes additional time to pull the necessary permits, and more still to find somewhere to locate the unit that is safe, legal, and has access to reliable, working utilities. Even if those obstacles can be overcome, finding capable contractors with time to do the work can be a significant challenge in the wake of a major disaster, further delaying the process. The first families in Southeast Texas to receive FEMA homes began moving in in early October, about five weeks after the hurricane struck. Many more remain on a waiting list.

“Last year’s Louisiana flooding was really the first test of this whole concept, the first time we actually told manufacturers to crank up into their full potential,” McKenna said. “There were issues, but we worked through them gradually.” In a normal year, FEMA deploys about 800 of its emergency housing units to disaster events, he said. The 2016 Louisiana flooding demanded almost 5,000 units in a matter of months.

From a sprinkler standpoint, the biggest difficulty proved to be securing parts for the external pump and tank assembly, which led to production delays. Today, about a third of the 3,000 sprinklered FEMA units shipped to Louisiana are still without the tank and pump systems, rendering the sprinkler systems inoperable, McKenna said. The storm also struck before FEMA had any program or training materials in place for the contractors tasked with installing the innovative systems, which increased the difficulty of finding contractors who could do the job, despite the intention to make the system a simple plug-and-play design.

Those lessons should help as the agency takes on the even bigger task of responding to Harvey and Maria. Manufacturers working with FEMA have made assurances that there will be no supply issues, that parts will be in place, and that units will be delivered on time. A training program has been developed for installers, and McKenna and others have been in the Houston area training the FEMA staff that will be overseeing the sprinkler installation contractors. The team has also made minor engineering tweaks to how the tank and pump connects to the sprinkler system, which should make installation even easier. At least that’s the hope.

“Things are always changing, and that forces you to adapt and react,” McKenna said. “With everything you do there are always ways to make things better, always places where you can find improvements. That’s exactly what we did.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.