Precision Fire Protection News

Proposed LNG Transportation by Rail

A proposal to allow bulk shipments of liquefied natural gas on US railroads has sparked criticism, stoked fears about public safety, and raised concerns among first responders. How should the safety community prepare for what’s next?

Last October, a few dozen HAZMAT chiefs, fire commissioners, emergency managers, and other safety technical experts gathered in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to discuss the ramifications of allowing large quantities of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to travel the nation’s railroads. What resources would be needed, for instance, if a train car carrying tons of LNG—a methane mixture cooled to –260 degrees F—were to tear open and release its cargo in a major city? What if it happened in a rural area with few, if any, emergency responders trained to handle such an event?

The meeting, called simply “Proposed LNG Transportation by Rail Town Hall,” was put on by the Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the National Fire Academy. For attendees, the discussion wasn’t a baseless hypothetical. For the first time, trains up to 100 rail cars long, each carrying more than 70 tons of LNG, may soon be rolling through many of America’s largest cities. That scenario was made possible last April, when President Donald Trump signed an executive order instructing the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) to write rules allowing the transport of LNG by rail.

A few days after the Lancaster meeting, PHMSA, a branch of the USDOT, unveiled a proposal to do just that. The three-month public comment period ended in January, and the final rule outlining how rail carriers should proceed could be out later this year.

The level of risk involved with hauling LNG by rail can vary widely depending on whom you ask. While applauded by energy companies and rail carriers, the PHMSA proposal set off alarms among other interests, including environmentalists, politicians, media outlets, and, notably, several public safety organizations. Those writing letters “strongly opposed” to the idea included the International Association of Firefighters (IAFF), the National Association of State Fire Marshals, and the National Transportation Safety Board, an independent federal agency.

Opponents have accused PHMSA of downplaying the potential risks of LNG and making unsubstantiated assumptions about the safety performance of the railcars that would carry the liquefied gas. The IAFF, pointing out that LNG will quickly evaporate into an immense and potentially flammable vapor cloud when exposed to ambient air, wrote that “it is nearly certain any accident involving a train consisting of multiple rail cars loaded with LNG will place vast numbers of the public at risk while fully depleting all local emergency response forces. Further, incident responses occurring without a robust cadre of highly trained responders, absent across most of America, will undoubtedly experience deadly and disastrous outcomes.”

Public backlash ramped up in January when attorneys general from 15 states and Washington, DC, submitted a letter lambasting the PHMSA for its “failure to take the public safety” seriously. “One mistake by a train carrying LNG gas could cause massive explosions and fires,” Oregon state Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum told a local news outlet. The condemnation carried over to national media, where news articles with headlines like “Trump Plan to Ship Natural Gas by Rail Stokes Fear of ‘Bomb Trains’” began to appear.

While federal agencies sort out the details of LNG via rail, first responders and emergency planners have been put in what’s become a familiar position: having to adjust to another new challenge in an ever-evolving energy landscape.

“I don’t know if hauling LNG by rail is smart or not, but what I do know is if it’s something that we’re going to be forced to deal with, there has to be some type of policy or regulation in place to make sure it’s done in a safe manner,” said Derrick Sawyer, the fire director of Trenton, New Jersey, and the former fire commissioner in Philadelphia, both hotbeds of industrial rail activity. “You have to make sure that everybody who’s going to be impacted has a seat at the table so that we have a broad overview of what the safety impact is and how we can mitigate and reduce the risk.”

Growth and threat

Lately, the rapid adoption of newer technologies like energy storage systems and electric vehicles have received the lion’s share of attention in responder circles. What’s often overlooked are the new response challenges generated by the resurgence of US oil and gas production over the last decade.

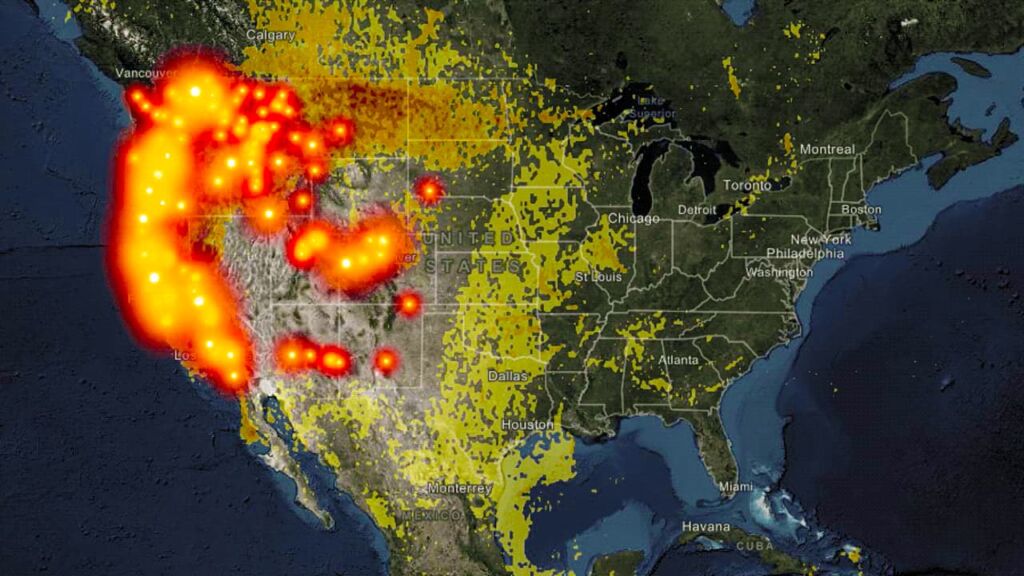

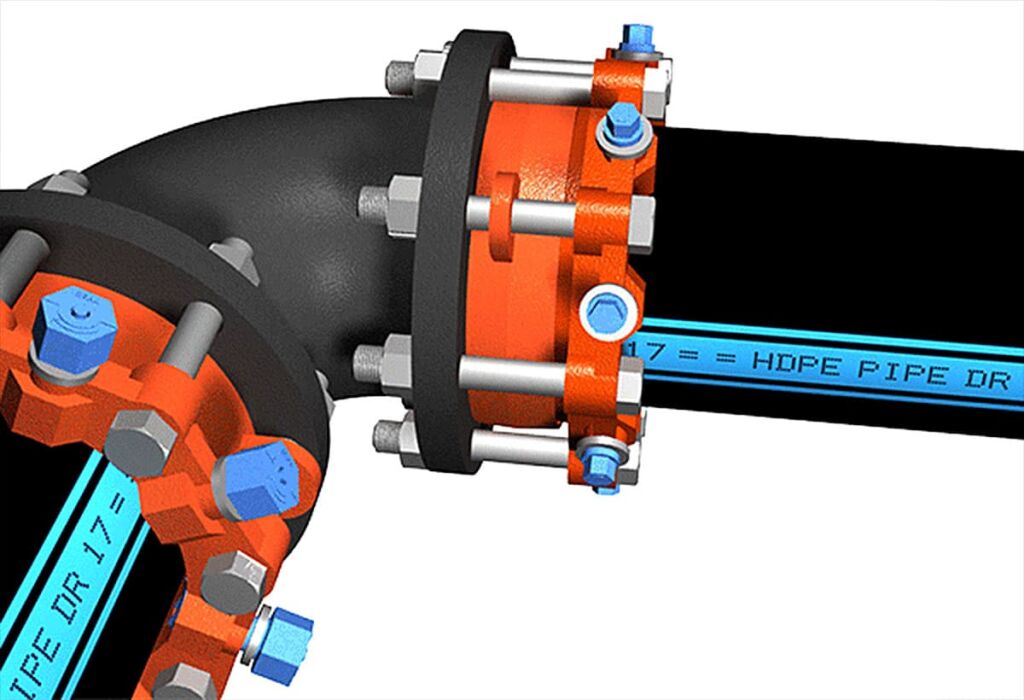

Just a few years ago, many energy experts believed the days of the US as a major fossil fuel producer were over. But new techniques for extracting oil and gas from the ground, including hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, have resulted in a dramatic turnaround. From 2005 to 2018, natural gas production in the US grew nearly 70 percent, to more than 30 trillion cubic feet, and the US went from a net-importer of LNG to one of the world’s largest exporters. The sudden glut of gas has caused domestic prices to drop and demand to skyrocket, resulting in the construction of billions of dollars of new infrastructure to process, store, and transport LNG. There are now seven LNG export terminals in operation in the US, and another 29 either proposed or under construction. As late as 2015, there were none.

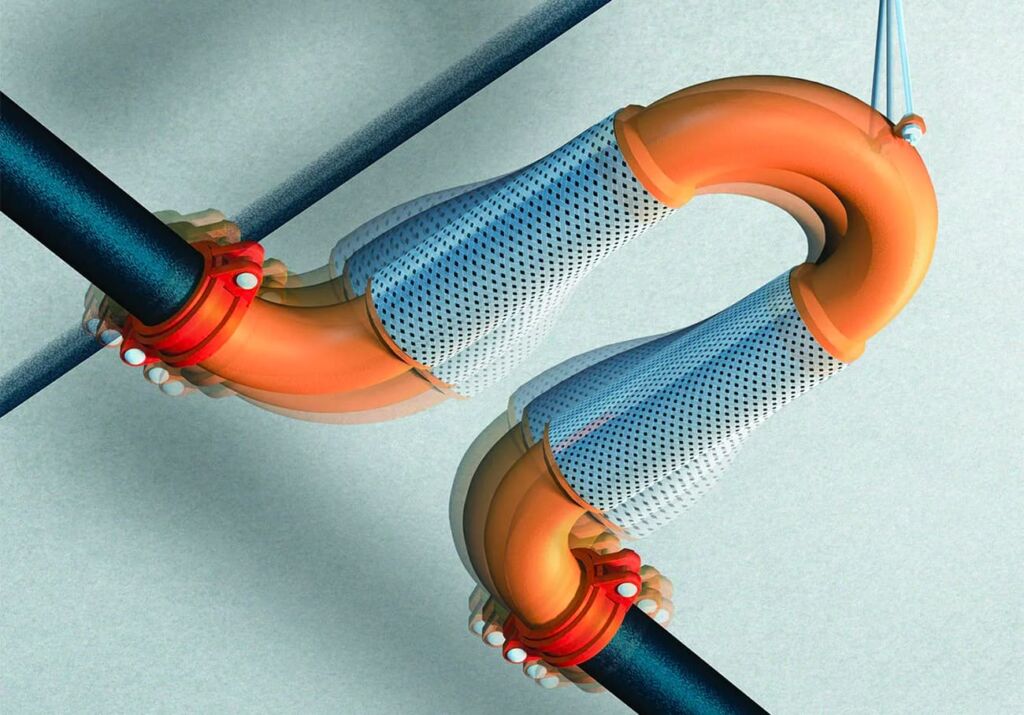

All of that gas needs to move from the shale fields of Texas, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere to storage and export facilities across the country. When not in pipelines, natural gas is almost always transported in its liquid form because of its superior storage capacity. The gas is chilled to –260 degrees F, which vastly condenses its volume—something akin to shrinking a beach ball to a ping-pong ball. The resulting LNG is typically shipped in vacuum-sealed, double walled cryogenic containers, which can maintain supercooled temperatures for about three weeks. Once it reaches its destination, the LNG is converted back to gas for a variety of purposes, including electricity generation, home heating, and fuel for vehicles, ships, and trains.

Trucks have been the primary LNG transport method over land, but they can only handle so much of the supply. With many pipeline construction projects around the country stalled for various reasons, energy companies see large-scale rail transport as a potential solution to supply bottlenecks. That, however, has created other concerns.

“In the event of a catastrophic accident involving a tank truck, the worst scenario is the release of 20 or 30 tons of product impacting the environment,” said Jorge Carrasco, who has responded to hundreds of train derailments as chief operating officer at Ambipar Response, the largest private HAZMAT response company in the world. “The worst scenario in a catastrophic train accident has the potential to release hundreds and even thousands of tons of product.”

The likely impact of a large LNG release in a rail accident isn’t clear. In its opposition letter, the IAFF drew a parallel with a 1998 explosion in Iowa involving a stationary 18,000-gallon liquid propane tank. In the incident, firefighters arrived on scene to find the tank on fire. When it eventually exploded, two firefighters were killed and seven others were injured. The US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board determined that firefighting force size and the lack of quality firefighter training were contributing factors. “This incident occurring in rural Iowa serves to demonstrate a likely outcome of any LNG tank car fire incident with an insufficient number of firefighters, common throughout most of North America, and inadequate firefighter training,” the IAFF wrote.

A key distinction, however, is that liquid propane is not LNG. In a recently published environmental impact assessment, PHMSA claimed that, even if an LNG rail incident resulted in a full release, LNG’s properties make it “unlikely that the derailment would result in an explosion.”

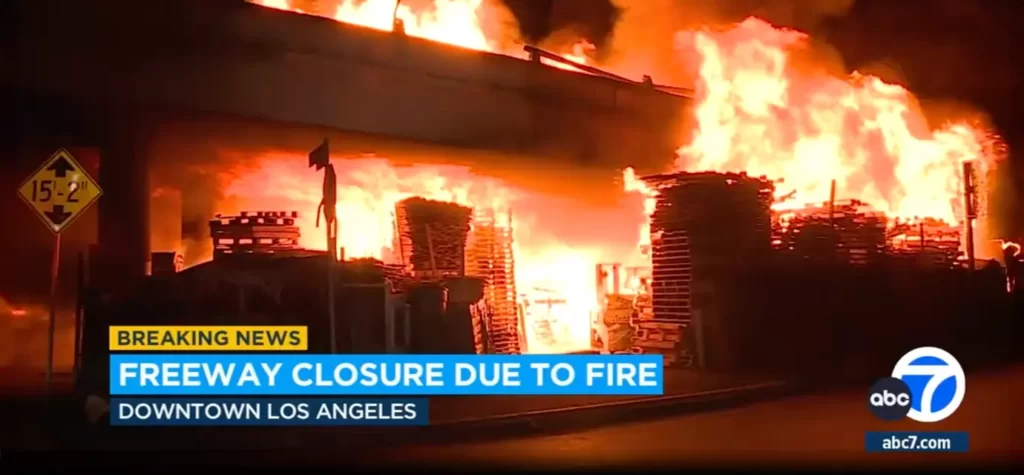

That assessment is echoed by Guy Colonna, the director for Industrial and Chemical Engineering at NFPA. In the 1980s, as a researcher with the US Coast Guard, Colonna participated in work that informed many of the LNG vapor cloud computer models still used today. “The fact is, it is really hard to blow up LNG. As part of our research, we tried to detonate it many times under many different scenarios and never could under typical conditions,” he said of the research. “You have to have the right concentration, the right amount of evaporation, and a delayed and perfectly timed ignition.” A more likely scenario is an LNG pool fire, he said, which results in large, very hot columns of fire.

Aside from fire, evaporated LNG can act as an asphyxiant in high enough concentrations and can cause severe burns due to its extreme cold. First responders would require special protection to get near it.

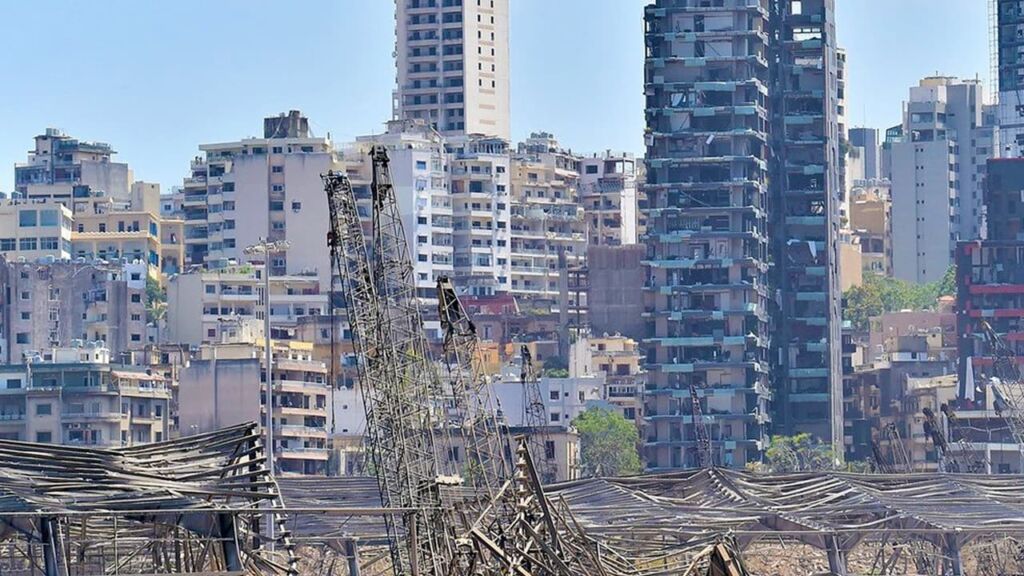

LNG’s chemical and flammability properties are well understood, and over the years it has a relatively good safety record—with a few notable exceptions. The most destructive incident on record occurred in Cleveland in 1949, when an LNG tank ruptured and spilled its contents into the city’s streets and sewer system. The resulting explosion and fire killed 129 people. More recently, an explosion occurred at an LNG plant in Algeria in 2004, causing 27 deaths. A natural gas pipe explosion in Belgium that same year caused 23 fatalities. A pipeline explosion in Nigeria in 2005 resulted in a fire that engulfed an estimated 27 square kilometers.

There have been spills and minor damage associated with tanker ships hauling LNG, but seemingly no major fires or explosions as a result of transporting LNG over land or sea. This includes a reportedly safe record of hauling LNG by train in Japan and Canada—where it has been allowed for years—and on two short rail lines in Alaska and Florida, which received a conditional permit to do so from PHMSA as part of a pilot program in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

However, all bets are off whenever you put wheels on a container, be it a truck or a train, said Gregory Noll, a current member and former chair of NFPA 472, Standard for Competence of Responders to Hazardous Materials/Weapons of Mass Destruction Incidents, and the moderator of the Lancaster discussion. “There is always a threat,” he said. “There is no risk-free answer here.”

Preparation is all

Even with the worst case in mind, all of the safety experts interviewed for this story are confident that the risks of hauling LNG by rail can be properly mitigated if smart decisions are made at the outset. Carrasco cited fertilizers, liquefied propane, chlorine, crude oil, and other chemicals that he described as “exponentially more dangerous and more complicated” than LNG to haul by rail. “If we take the proper precautions and implement the right engineering control procedures, I do not see any major impediment to running a very safe LNG transportation operation,” he said.

“LNG can be dangerous, but of all the bad-day scenarios, one involving LNG is not at the top of my list,” Noll said. “If you look at a lot of the dissent around this proposal, it’s primarily related to making sure LNG is safe to move, making sure that we have the right container for it, and that the container is safe. They also want to make sure our communities are prepared for this risk.”

Regardless of the details in the final LNG rule, Noll and others say, there is a lot of work that communities and public agencies can and should be doing now to prepare for rail accidents, regardless of the materials involved. Responders at the Lancaster responder meeting in October emphasized the importance of planning and cooperation between railroads, safety agencies, and other community groups near rail routes.

Among the entities singled out as being critical are local emergency planning committees (LEPCs), which were created as part of the Community Planning and Community Right to Know Act. The act, passed by Congress in 1986 after a string of chemical industrial accidents, established more than 3,000 designated local emergency planning districts around the country and required industries within those districts to report on the storage, use, and releases of hazardous substances. The LEPCs—comprised of representatives from industry, elected officials, hospitals, facilities, community groups, and others—are charged with using that mandated industrial reporting to develop comprehensive emergency response plans to protect their communities from risks.

In many parts of the country, however, LEPCs exist only in theory. Rick Edinger, a career firefighter and the current chair of the NFPA 472 technical committee, said many LEPCs have essentially died. “Those of us in the HAZMAT industry are very concerned about that, because LEPCs are where you sit down together with industry partners, government officials, and emergency responders and talk through the problems and develop relationships,” he said. “You need to meet and plan those things prior to an event so that when the event happens and the thing is out of control, you’re not meeting somebody for the first time.”

Rail operators are not required to give local authorities specific details on the quantities or timing of hazardous materials passing through their jurisdictions, but they do provide agencies with a list of the 25 most hazardous materials that routinely come through, and an emergency number for responders to call. Through LEPCs and working with industry, emergency response agencies can conduct what’s called a commodity flow study, which can identify the types and amounts of hazardous materials routinely transported through and within their jurisdictions. In reality, though, individual fire departments—even major ones—“very rarely know what’s specifically coming through the city at any given time unless something bad happens,” said Sawyer, the former Philadelphia fire commissioner.

Photos from William Vantuono/Railway Age

Whether through LEPCs or some other mechanism, it is critical for response agencies to foster relationships with railroad representatives, tour train yard facilities, and conduct exercises to make sure each of the parties involved—fire, police, railroads, regional emergency planning boards, and hospitals—are clear about the plan if an incident occurs, Sawyer said. “You go through each phase of the incident so that everybody understands what each others’ roles are, what resources we have and what we need, and how we will communicate the emergency to our citizens to make sure everyone is safe.”

The HAZMAT and fire department experts who were interviewed for this story said that, in their experience, the railroads have been willing partners, offering time, training resources, and planning assistance. The biggest rail lines, designated as Class I railroads, also have their own HAZMAT officers placed strategically across the country’s 140,000-mile freight rail network, and have highly specialized private HAZMAT companies at the ready in case of a large spill, fire, or other major incident. These teams have the equipment and training to perform complex maneuvers like patching rail car leaks, safely burning off excess gas, drilling additional pressure release valves, or even intentionally blowing up tank cars.

However, depending on the accident location, these advanced crews can sometimes take a couple of days to arrive. Carrasco, who helped develop these advanced tactics, said that a prepared fire department can make his job a lot easier by conducting a proper site evaluation of an incident and evacuating and protecting the surrounding area. “In my experience, if you are working with a fire department with railway emergency training, things are going to be very smooth,” he said. “If the first responders on site have no idea what to do, it’s going to be very complicated.”

Responders at the Lancaster meeting also had concerns about what additional training might be needed for local responders to prepare them to handle an LNG release. Edinger and Noll believe that the lessons learned in the mid-2010s from educating responders in the wake of several Bakken crude train accidents could inform LNG safety training (see “Learning from Crude”).

Training responders on the properties of the hazardous materials they encounter is critical to mounting a successful risk-based response, which is one of the mantras in the NFPA hazmat documents, including NFPA 472, Edinger said. “Knowing the characteristics of the commodity is important because that helps you develop your incident action plan and figure out what you can and can’t do,” he said. “There’s a big difference between crude oil and LNG, but the basic premise of the response is the same: You look at the situation, figure out what your best option is, implement that option, and then evaluate whether it’s working or not. Decisions are based on incident facts, science, and circumstances. That’s risk-based response in a nutshell.”

For the vast majority of fire departments facing a major LNG derailment, the best option will likely be to isolate the area and stay far away. “It’s just such a massive incident, and it’s on such a large scale that your job is to get there, assess it, and make sure you don’t get anybody else in harm’s way,” Edinger said. “And start calling for help.”

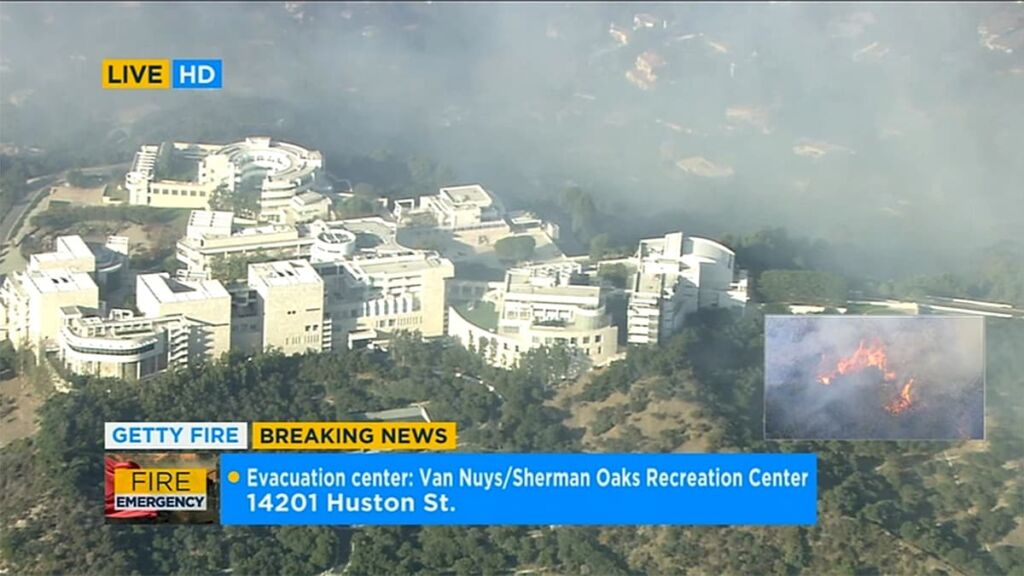

Top photograph: Mountain View (CA) Fire Department

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

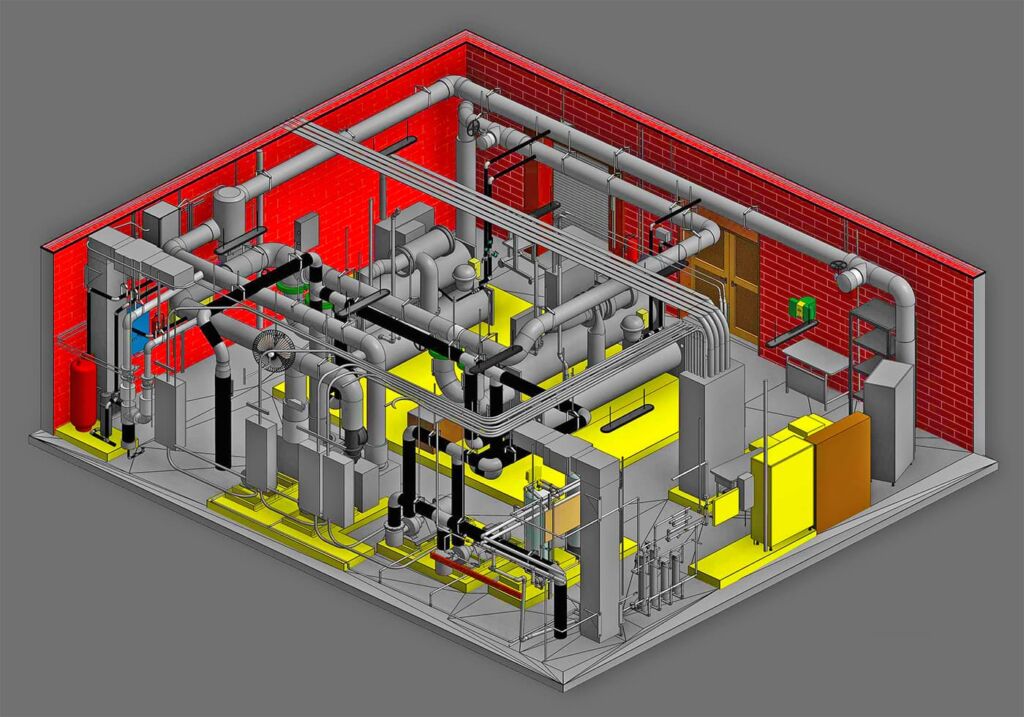

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.