Precision Fire Protection News

$110 Million Dollar Loss After Occupancy Change

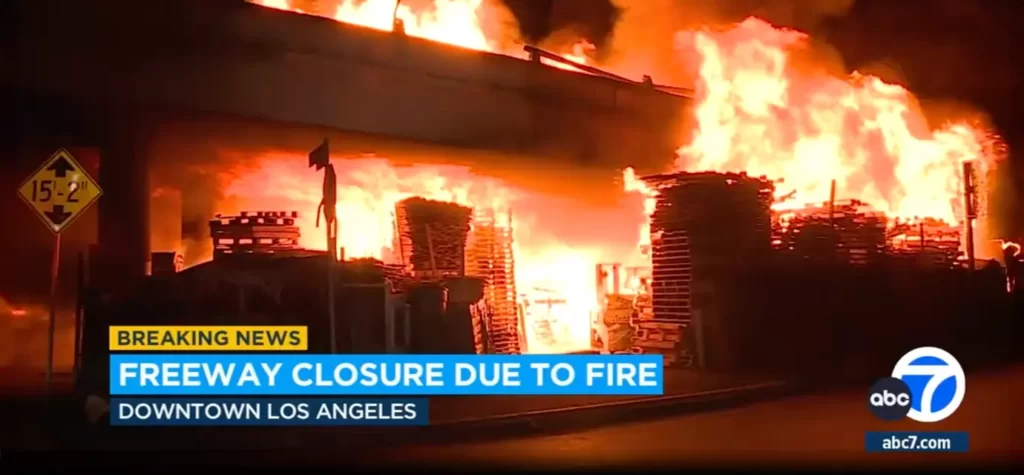

General Electric was planning a sprinkler upgrade for a large storage facility in Kentucky that over the years had undergone a slow but significant change of occupancy. But the company had made little progress on the plan when a devastating fire occurred in 2015. The result: A $110 million loss.

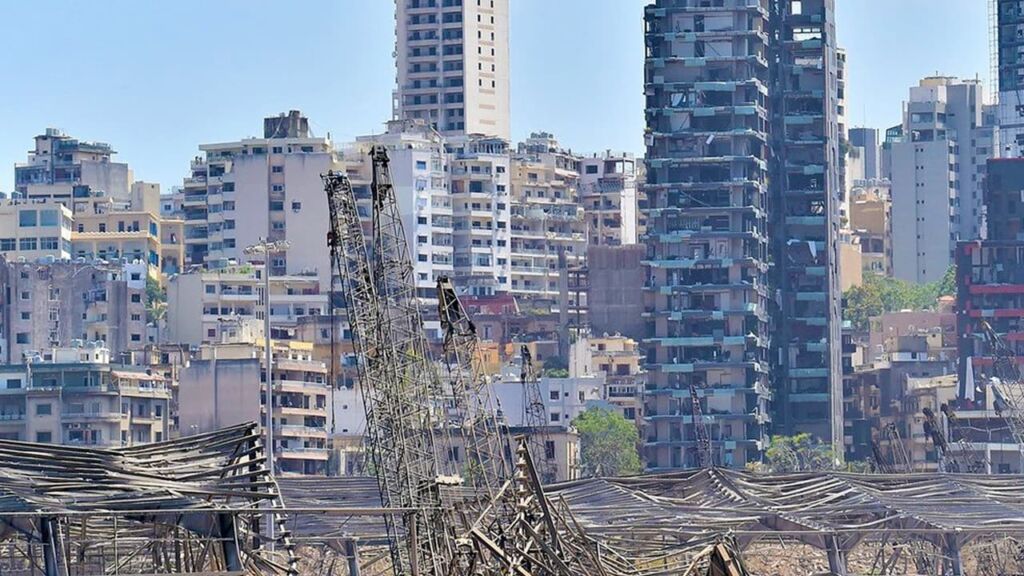

Just hours after a fire was reported in a General Electric storage warehouse in Louisville, Kentucky, on the morning of April 3, 2015, it was clear to fire officials that the building would be a total loss. Plumes of black smoke poured from nearly every square foot of the building’s footprint, so thick that people within a two-mile radius of the facility were asked to shelter in place. “It was definitely the biggest fire I’d ever seen in one building,” said Chris Gosnell, chief of the Okolona Fire Protection District, one of 17 departments that serve the Louisville area.

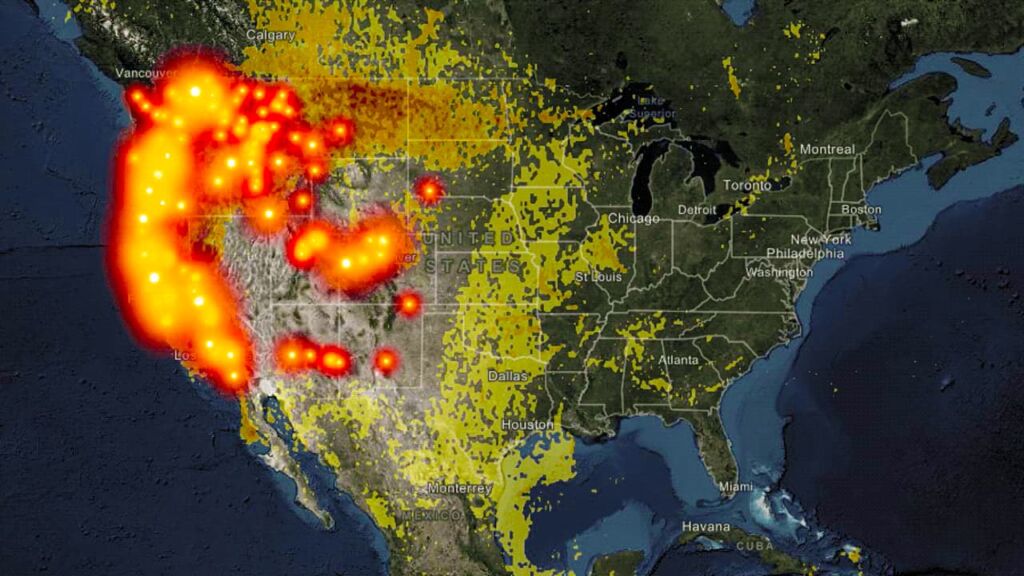

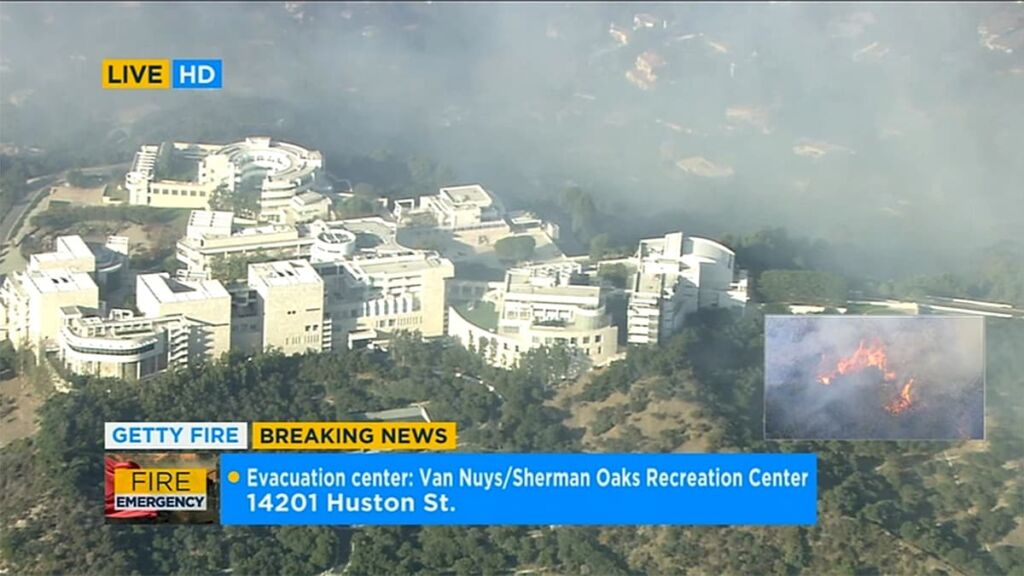

Over 100 firefighters from 18 departments responded to the blaze, which caused an estimated $110 million in damage—the country’s largest storage occupancy loss in 2015 and the year’s third-costliest fire overall, behind two California wildfires that accounted for nearly $2 billion in losses. No injuries were reported in the GE fire. Its cause was never determined, although it was narrowed down to either an electrical failure or a lightning strike—a storm had dumped more than eight inches of rain on the area in the days preceding the fire.

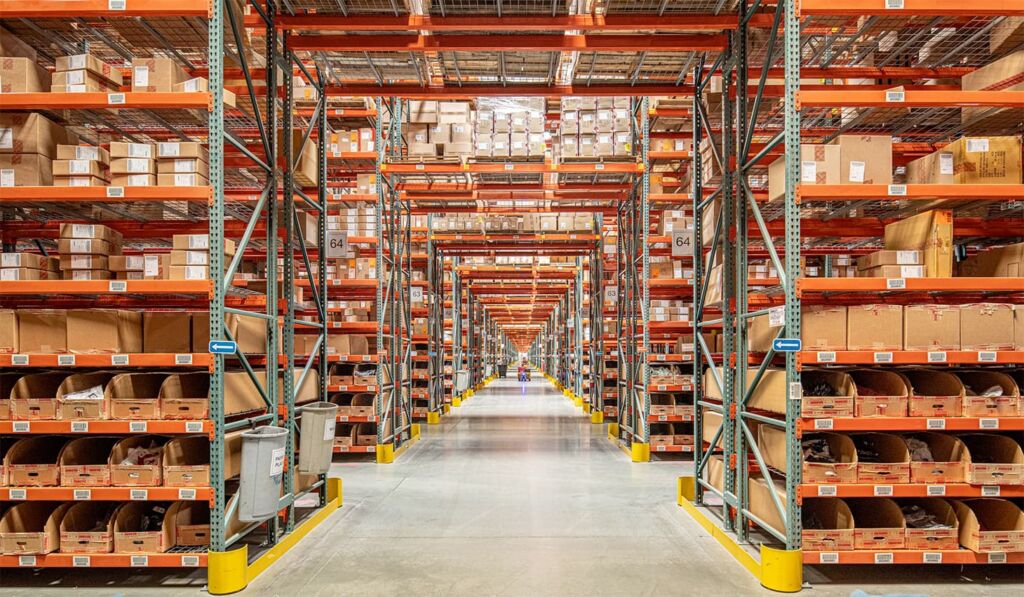

The 700,000-square-foot building was part of the General Electric Appliance Park, a roughly 900-acre complex that has been home to GE’s appliance division since the 1950s. The building that burned was known as Appliance Park 6, or AP-6. The building was originally used to manufacture air conditioners, but over time manufacturing operations inside the space shrunk until more than 85 percent of it was used for storing appliance parts, everything from metal nuts and bolts to plastic hoses and rubber belts. The parts were stored in cardboard boxes or plastic cartons that were either stacked on top of one another in blocks reaching 12 feet high, or tucked away on wooden pallets in 24-foot-tall single- and double-row racks. On average, AP-6’s ceilings reached 30 feet, with the portion of the building devoted to storage covering an area equivalent to nearly 11 football fields.

The 900-acre General Electric Appliance Park in Louisville, Kentucky, outlined in blue. The building known as AP-6, one of a number of large storage and production facilities on the property, is outlined in red. Photograph: Google Earth

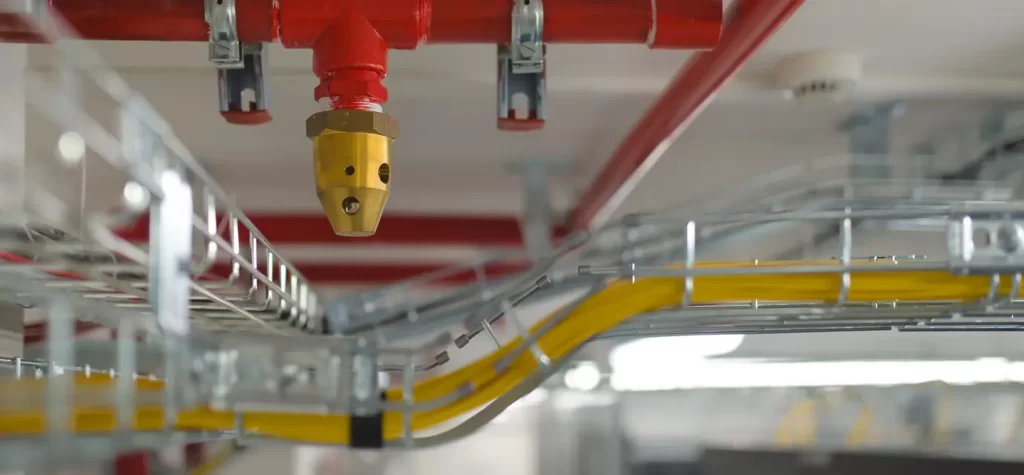

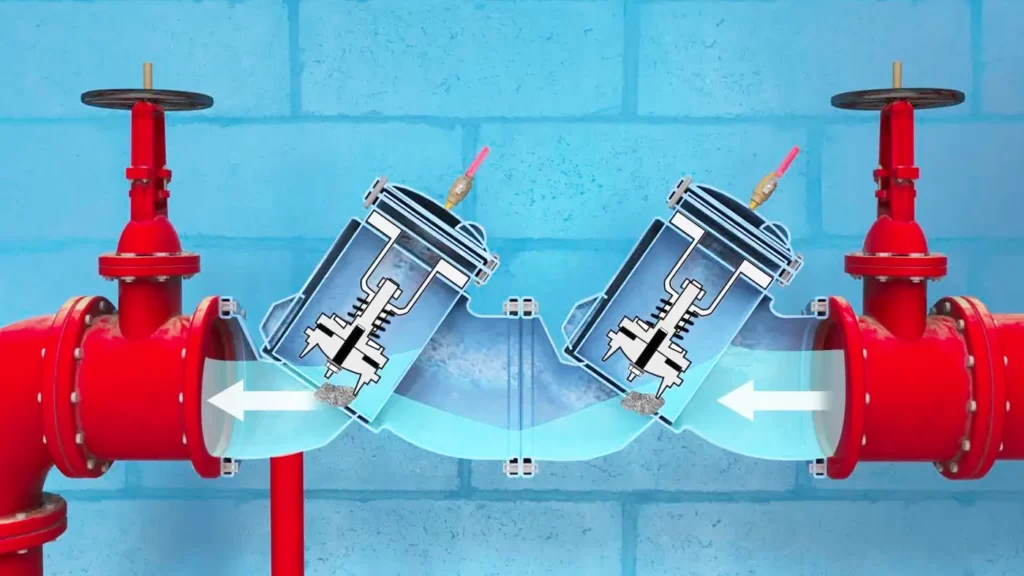

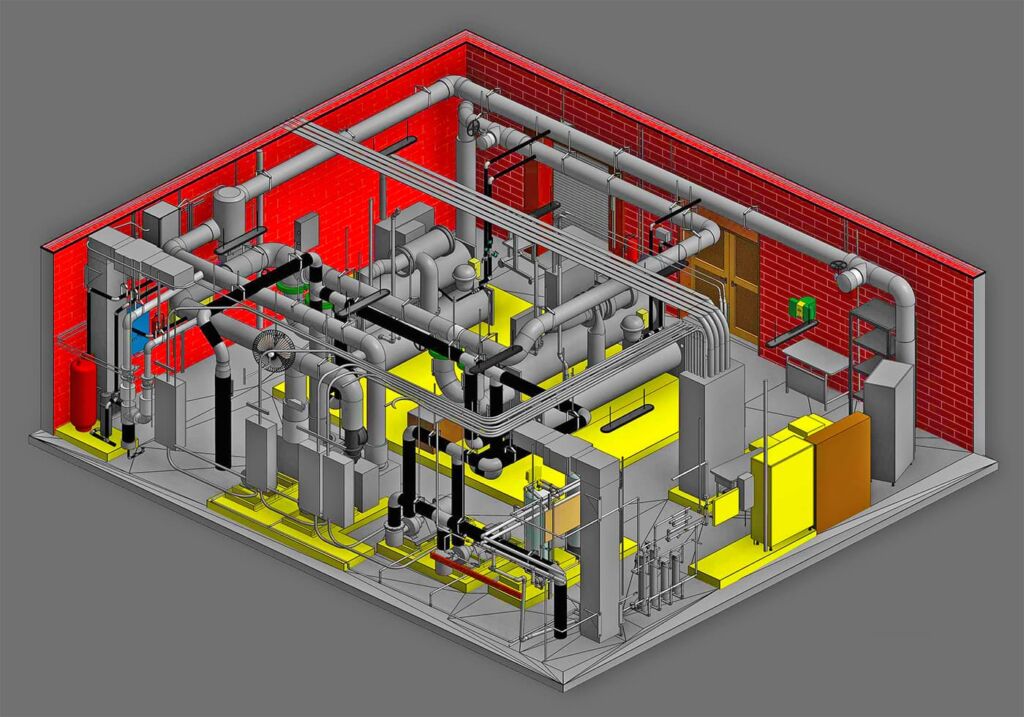

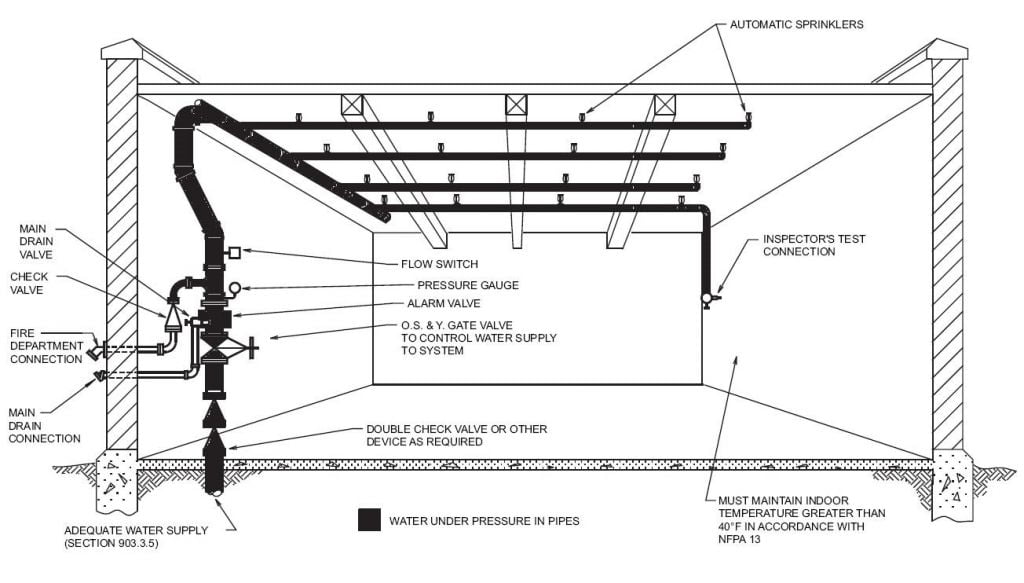

While Appliance Park had a once-robust water-based fire protection system, with hydrants and sprinklers fed by an on-site water supply and fire pumps, the system was overwhelmed by the rapidly spreading fire. Most of the fire pumps proved inoperable on the day of the fire and the ceiling sprinklers inside AP-6 weren’t engineered to control fires involving highly combustible materials like plastics.

The GE fire illustrates what can go wrong when building owners fail to make changes to water-based fire protection systems after the use of an occupancy changes, said Robert Duval, NFPA’s senior fire investigator who visited the complex following the fire. When an occupancy change occurs, a corresponding change in fire protection systems can be required to meet the new hazard. Too often, though, that change never happens, Duval said, partly because it can be difficult to identify that a change of use has even occurred in industrial spaces. In spite of provisions found in NFPA 1, Fire Code, that require change of occupancy to comply with the rules for that new occupancy, building owners and operators may be unaware of the implications of not abiding by that simple rule.

Duval described the gradual change-of-use process often seen in industrial spaces as “a slow creep,” compared to the abrupt and obvious change of, for example, a grocery store closing and reopening as a restaurant. In industrial spaces, the change of use or change of occupancy can occur over a period of years or decades.

Compounding the creeping change-of-occupancy issue was the sprinkler system itself. When a sprinkler system is in place, as there was inside AP-6, Duval said, an illusion of safety can exist—at least for those unfamiliar with the complexities of systems and the occupancies, products, and commodities they are designed to protect. “People will look up and say, ‘There are sprinklers here, so it’s fine,’” Duval said. “But they don’t understand the engineering behind it and the physics behind it. The sprinklers have to be designed for the occupancy, and in the case of a storage occupancy they have to be specifically designed for the items being stored and the configurations that are being used.”

AN OVERWHELMED SYSTEM

In some respects, the GE fire was a perfect storm of variables. The heavy rainfall occurring at the same time as the fire placed additional stress on local fire departments—Okolona alone responded to 65 water rescues in the weeklong period of severe weather that started two days before the fire. Additionally, staffing at Appliance Park was thin because it was Good Friday. But Duval said he is confident these factors would not have taken on the importance they did in determining the outcome of the fire if GE had been compliant with NFPA 13, Installation of Sprinkler Systems, and NFPA 25, Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems. “There could’ve been nobody in the building and it could’ve been raining for months, and I think the outcome still would have been better,” he said.

An ordinary-hazard sprinkler system designed in the 1950s, like the one inside AP-6, can still be effective if it’s battling the type of fire it was designed for, explained David Hague, principal fire protection engineer at NFPA. “Any sprinkler system is highly effective if it’s designed and installed and maintained properly, but that also means when the use of a building changes, you need to reevaluate to make sure it’s still an adequate system for the hazard it’s trying to protect,” he said. In the case of the GE fire, it wasn’t the age of the sprinkler system that contributed to the spread of the fire; rather, as Hague put it, the system “had no chance of keeping up with a challenging fire” because of how it was engineered. The sprinkler system was designed to control fires involving noncombustible metal parts used in the manufacturing of air conditioners, not the high concentration of plastic and rubber that was actually stored there.

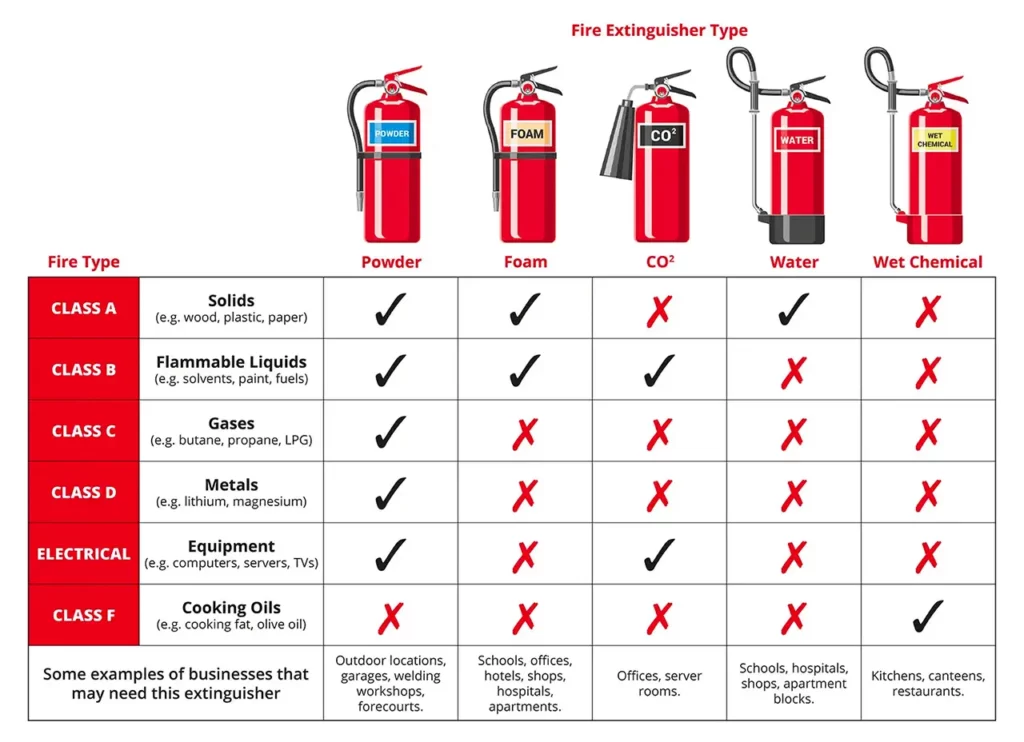

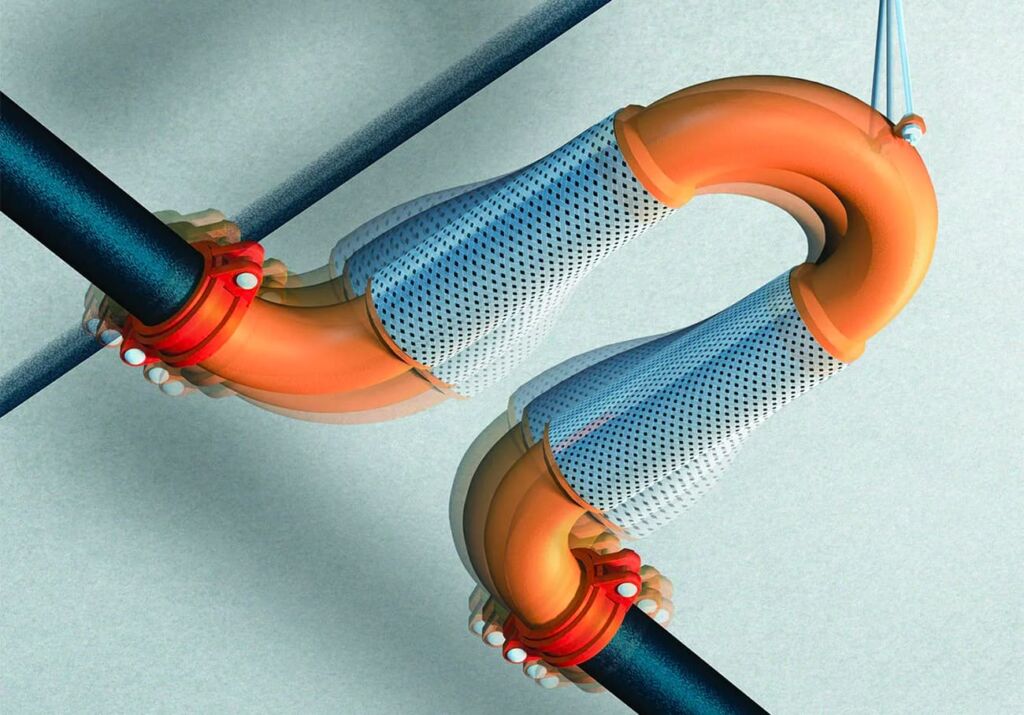

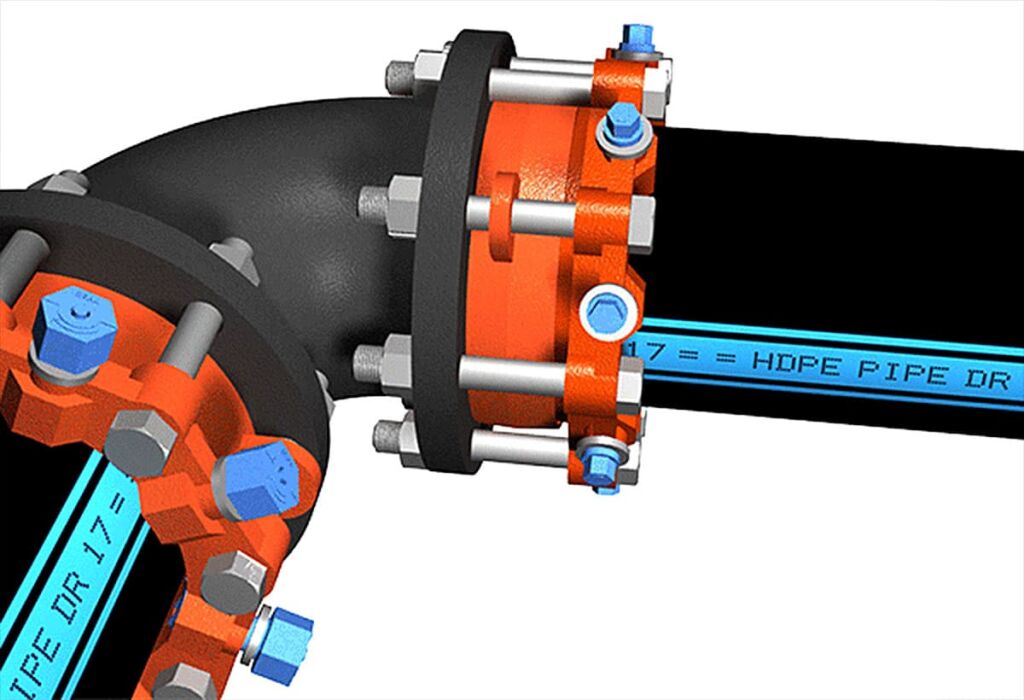

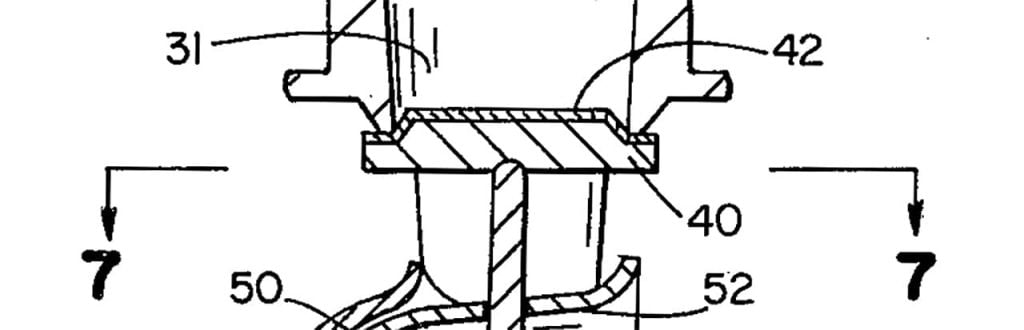

There’s a long list of criteria considered in determining what kind of sprinkler system is appropriate for a given space, Hague said. But in the simplest terms, systems designed to control or suppress large fires involving highly combustible materials will generally include sprinklers with a large diameter orifice, allowing more water to flow out of them. The sprinklers with the largest orifice, known as early suppression fast response (ESFR) sprinklers, were designed in the 1980s, Hague said, and would’ve been an option for an improved protection scheme in AP-6. Another option for GE, according to the provisions of NFPA 13, would’ve been to evaluate the effectiveness of the ceiling sprinklers, coupled with the addition of in-rack sprinklers, to establish a protection scheme, Duval said.

The problem was even more complex, however, because simply upgrading sprinklers won’t do much good if the water supply can’t meet the system’s demand, and Appliance Park’s water supply had severe deficiencies. For example, Hague estimated that an ESFR sprinkler system in a warehouse demands about 1,700 gallons of water per minute, while the top-end of demand for an ordinary-hazard system in a warehouse is about 1,500 gallons per minute.

The local fire service was unaware of how much had changed inside AP-6 over the years. “In the past, [we] didn’t get over there,” Mike Allendorf, Okolona’s district fire marshal and assistant chief, said of the restrictions GE used to put on the entry of local firefighters into the complex. The restrictions, he speculated, stemmed from a deep-seated sense of self-sufficiency; when it was constructed in the late 1950s, the complex was designed to be entirely self-sufficient, with its own water supply, security force, post office, and even a state-certified fire brigade, whose services lasted until 2002. After that, the Black Mudd Fire District, which was absorbed by Okolona in 2003, assumed fire suppression duties for the property. But GE maintained self-inspection status. In fact, the property was never inspected by a fire service agency prior to the April 2015 fire.

Early Stage A photo taken by a worker of the incipient fire in the AP-6 building. Photograph: Louisville Metro Arson Squad

Even so, deficiencies in the complex’s water-based fire protection system were known prior to the fire. Yearly evaluations of the complex by the insurer Factory Mutual shed light on the problems. For example, a 2003 risk report by FM stressed the need to update the sprinkler system inside AP-6. A later FM report indicated that several fire hydrants and fire pumps within the GE complex didn’t work properly.

FM’s concerns were substantiated on the day of the fire. Faced with an inadequate water supply, firefighters had to lay nearly 15,000 feet of hose just to establish “some sort of positive supply” of water, said Jody Craig, Okolona’s battalion chief, who was the first incident commander at the scene. “We had lost a quarter of the building before we even had a positive water supply,” he said. In total, only one of the complex’s eight fire pumps worked, driving firefighters off the property to find other water sources, according to a report from the Louisville Fire and Rescue Metro Arson Squad, which investigated the fire.

The report also stated that very few people who worked in AP-6 observed sprinklers working well as they fled the building. Twelve employees reported not seeing sprinklers flowing at all during the fire, and one said he saw sprinklers flowing but “they were not effective and water was not hitting the floor,” the report states. NFPA’s 2013 “U.S. Experience with Sprinklers” report suggests that scenarios similar to those described by the employees are the leading cause of so-called ineffective sprinkler performance. Forty-four percent of cases of ineffective sprinkler performance resulted from water not reaching the fire, while 30 percent resulted from not enough water being released, according to the report.

Duval said he wasn’t surprised the FM reports so accurately foreshadowed a large-loss fire. Problems like the ones at the GE complex are common and a major concern among insurance companies responsible for covering the losses, according to Duval. “This is the sort of thing that folks in the insurance industry are looking for all the time, because this comes back to bite you,” he said. “If you allow it to happen, you stand to lose the entire building or a large part of the building.”

Gosnell, Allendorf, and Craig, the three Okolona fire officials, all agreed that had their department been aware of the problems beforehand, there is a good chance the outcome would have been better. Even if GE hadn’t acted to fix the issues before the fire, they said, they would have at least responded to the incident knowing they wouldn’t be able to rely on the complex’s water supply. “We would’ve been more prepared,” Allendorf said.

THE COST OF DELAY

With the dangers of ignoring necessary changes in fire protection systems well-documented, why would building owners choose against making the changes? The most common answer, Duval said, is to avoid the associated costs. Between contracting a professional to determine what work needs to be done and then paying for the work to get done, which can be as extensive as digging up water lines and replacing entire piping systems, the costs are often high, he said.

But doing nothing is not a risk building managers should feel comfortable taking, Duval added, since the cost of a large-loss fire far outweighs any costs associated with preventing that kind of fire. According to NFPA’s 2015 “Large-Loss Fires in the United States” report, the losses from the 10 large-loss fires that occurred in industrial spaces in the U.S. in 2015 totaled nearly $320 million—about 70 percent of the losses of all large-loss structure fires in the country that year. In most of those 10 fires, which mainly occurred in manufacturing spaces, problems with, or a lack of, fire suppression systems were cited as contributing factors. For example, the details of an October 2015 fire that caused $10 million in damage to a Pennsylvania warehouse were strikingly similar to what happened in Louisville. While there was a fire sprinkler system present in the warehouse, the report states it was “ineffective because the sprinkler heads were above the racks and water could not reach the fire.”

Improvement Plan GE said it intended to update the appliance park’s aging fire protection system and was working with the local fire department on a plan that included new sprinklers, alarms, piping, and fire pumps. Photographs: Louisville Metro Arson Squad

GE intended to update Appliance Park’s fire protection system and was working with the Okolona Fire Department on a plan that included investing in new sprinklers, alarms, piping, and fire pumps. But no significant improvements had yet been made by 2015, a situation compounded by the fact that the timeline for the project stretched over several years and that GE retained its self-inspection status for the property. GE “was aware of the problems,” Duval said, but it “chose not to address them immediately.” A GE spokeswoman contacted by NFPA Journal said the company did not wish to comment on the AP-6 fire.

In the wake of the fire, Louisville fire officials decided to take a closer look at the area’s two other properties with self-inspection status—both Ford Motor Company factories—“just to see that we weren’t having that same kind of slowly creeping change of use or occupancy,” Allendorf said. Gosnell said one of those factories is in Okolona’s jurisdiction, and an inspection of that property uncovered no fire safety concerns.

In 2016, the Haier Group Corporation, a Chinese consumer electronics and home appliance company, bought GE’s appliance division and now owns Appliance Park, which is still run and staffed by GE and bears the same name. Allendorf said the complex’s water-based fire protection system is now about 85 percent updated, and his department meets with GE management on a quarterly basis to discuss fire safety. Gosnell described his department’s current relationship with the Appliance Park as “phenomenal.”

The plot of land where the scorched warehouse stood is now a grassy meadow filled with trees and walking trails for employees.

(SOURCE: NFPA)

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.