Precision Fire Protection News

Learning Curves and Unknowns in Cannabis Fire Protection

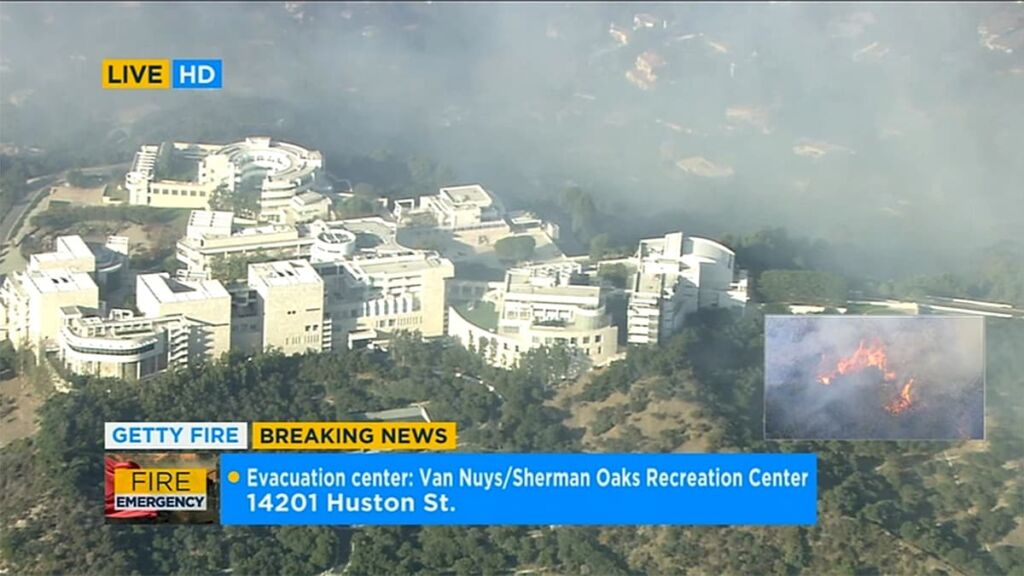

The New Face of Pot: Experts and investors are convinced that legal marijuana will soon be one of the world’s largest industries. With millions of square feet of growing and processing facilities being built from Newfoundland to California, fire safety officials across North America face steep learning curves and many unknowns.

In June, the fifth annual Cannabis World Congress & Business Exposition occupied the sprawling Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York City. A confident enthusiasm permeated the proceedings, which included talks from CEOs, professional athletes, and the actor Whoopi Goldberg. On the expo floor, hundreds of exhibitors hawked a vast range of products and services. Deep-pocketed investors mingled with marijuana industry executives. It was easy to understand the buoyant mood around one of the world’s fastest growing industries: estimates put the potential future U.S. legal cannabis market as high as $100 billion annually, five times larger than the NFL and twice as big as the country’s wine and ice cream markets combined.

When it comes to marijuana legalization and market expansion, “there is a feeling of real inevitability now,” is how one Colorado manufacturer put it to me.

Wall Street veteran and cannabis investor Sumit Mehta told a rapt audience during his talk on the state of the industry that he expects full federal legalization by 2021. “Money is pouring into this space, and one can see the political tides in this country shifting,” he said. In the near future, “restaurants will be offering cannabis pairings. Marijuana tinctures will be on the shelves of every pharmacy in America.”

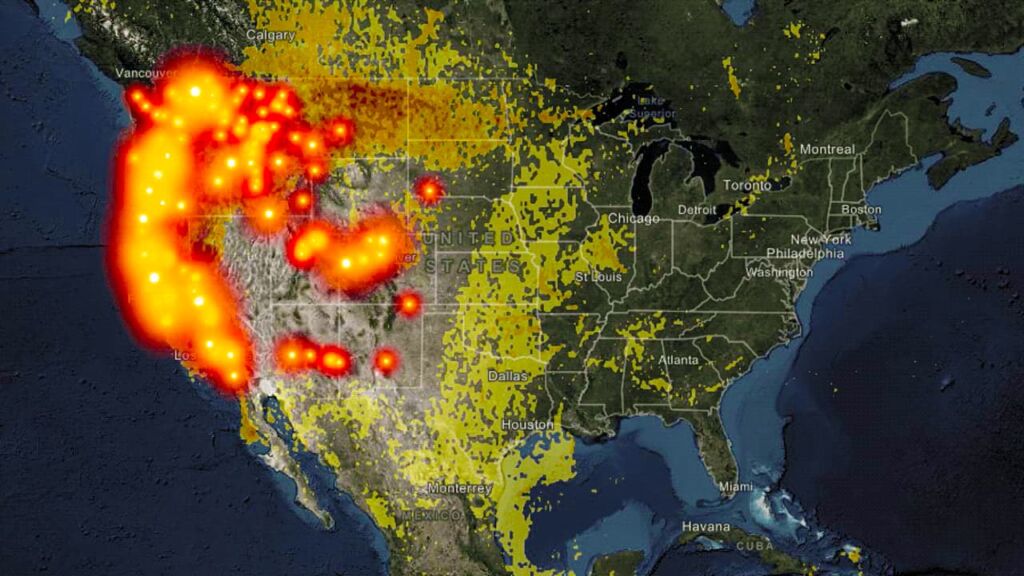

So far, 2018 has given the industry many reasons to be optimistic. California, the world’s fifth-largest economy, opened its first recreational pot shops January 1, the beginning of what is expected to be a $5 billion industry by next year. Recreational marijuana retail stores opened July 1 in Massachusetts, where sales are expected to surpass $1 billion by 2020. In Canada, the government voted in June to fully legalize recreational adult use of marijuana, with sales expected to begin nationwide in the fall. The five largest publically traded marijuana companies in Canada are already each valued at more than $1 billion, according to the finance newspaper Barron’s.

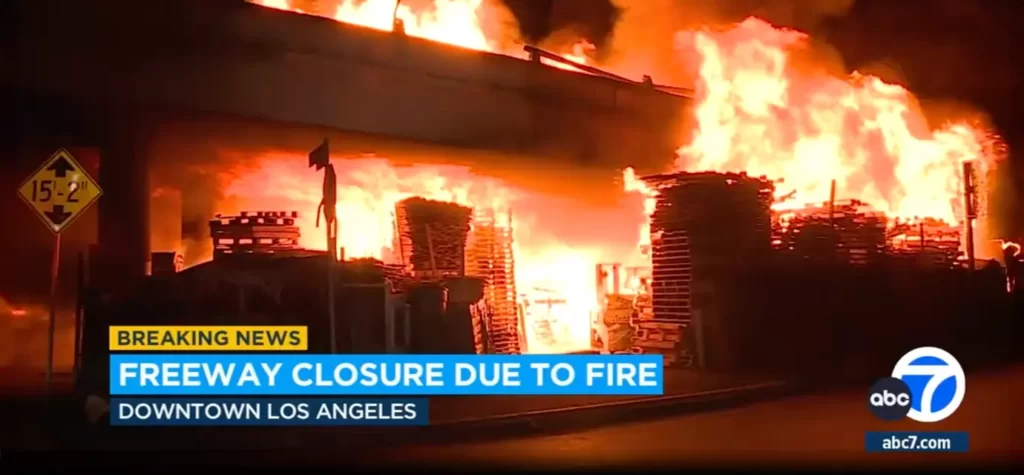

But while investors and entrepreneurs are delighted over the continued spread of legal sales and manufacturing of cannabis products, many regulators, inspectors, and fire departments view the developments with trepidation. Most new industries present unique challenges and steep learning curves; few, however, are growing as swiftly, are as multifaceted, or are as committed to innovation as the marijuana industry.

The industry’s rapid expansion has left fire officials across the country searching for answers, says Ray Bizal, NFPA’s director of regional operations, who has given upwards of 30 presentations on fire safety in the commercial pot industry for fire officials and city governments across the U.S. “The average fire department knows next to nothing about this industry,” he told me. “I hear a lot of people say that they just sort of stumbled across a marijuana facility and they’re asking themselves, ‘what do we do?’ Most jurisdictions have never dealt with this business before.” Recognizing that, last year NFPA published a new chapter in NFPA 1, Fire Code, on marijuana growing, processing, and extraction facilities. Jurisdictions in Massachusetts and Michigan are already requiring new grow and processing facilities to follow regulations in the new chapter.

The jurisdiction with perhaps the most experience regulating legal pot is the city of Denver, and perhaps no other fire agency in the world knows more about the fire hazards of marijuana grow and processing facilities than the Denver Fire Department. Since Colorado became the first state to legalize recreational pot on January 1, 2014, metro Denver has become something akin to the Silicon Valley of weed. Nearly 500 separate marijuana facilities, comprising retailers, growing and processing facilities, and testing centers, have opened in Denver over the past decade, and the city has issued more than 1,100 pot-related business permits. Annual pot sales here have more than doubled since recreational legalization, from $699 million to about $1.5 billion last year. Dozens of companies compete to produce the best marijuana flower, edibles, lotions, drinks, dermal patches, waxes, and other cannabis products.

In the summer of 2015, I visited Colorado to report on the fire and life safety hazards of the industry for the NFPA Journal cover story, “Growing Pains.” I asked Brian Lukus, a fire protection engineer with the Denver Fire Department and one of the nation’s leading fire service authorities on the marijuana industry, to reflect on the progress his department had made in understanding and regulating the industry. “I’m comfortable with where we’re at,” he said then. “But if you asked me six years ago if I was comfortable, I might have said yes then, too. The reality is that every few months there is something new.”

With the marijuana industry ramping up worldwide, and with millions of square feet of new marijuana production facilities planned for the U.S. and Canada in coming years to accommodate new legal markets, I travelled back to Denver this spring to see what had changed and what further lessons could be learned from the city that has all but pioneered regulation of this potentially massive industry. I met with government officials, equipment manufacturers, growers, regulators, fire inspectors, engineers, industry groups, and more. They paint a picture of an industry in constant motion, always advancing, as regulators struggle to stay a step or two behind.

The Denver experience

Three words Mark Rudolph hates to hear are “research and development.”

Rudolph, an inspector with the Denver Fire Department, specializes in the city’s thriving legal cannabis industry and offered, along with Lukus, to be my guide on a tour of several of Denver’s marijuana manufacturing and processing facilities. “Usually [R&D] means they’ve found some other chemistry they want to experiment with—and who knows how they’ll use it or what for,” Rudolph said as the three of us drove through suburban Denver. “The solvents run from water to dichloromethane. Anything they can experiment with they will try to use.”

Rudolph is referring to the process of making marijuana concentrate, an oily substance of highly concentrated THC or CBD, the two most widely used plant compounds. While the uninitiated may still think of marijuana primarily as a smokeable plant, marijuana-infused products like edibles and lotions, made using concentrate, are expected to soon account for nearly half of all cannabis-related sales in Colorado and elsewhere. An ounce of concentrate sold for an average of $1,400 in the U.S. last year, more than an ounce of gold, according to industry sources.

This cannabis gold is produced via an industrial process that uses solvents to strip out THC and CBD from the raw plant material. Solvents run the gamut, from hydrocarbons like butane and propane to liquid CO2 to alcohols like isopropanol. After the extraction process, the resulting concentrate is further refined and purified utilizing other potentially hazardous substances. Concentrate manufacturers often tweak their processes or alter their equipment in an effort to follow new fads or to experiment, just as brewers alter recipes for batches of beer, Rudolph said. Less scrupulous manufacturers sometimes seek out newer and novel—and, in some cases, potentially dangerous—solvents and methods, seeking to make a slightly different product with subjectively better qualities. It’s all about staying ahead of an ever-evolving consumer demand.

“The marijuana consumer mentality that has emerged here in Colorado is a lot like a craft beer consumer mentality,” Eduardo Provencio, the general council of a cannabis manufacturer called Mary’s Medicinals, told me on one of the stops of our tour. “People like this strain or that strain. They are very discerning.”

This incentive to experiment is what keeps inspectors like Rudolph up at night. At the first stop on our tour, I get a glimpse of a result of all this tinkering. A business owner we’re visiting holds up a small glass vial containing clumps of coarse crystals, which he tells me are up to 99.9 percent pure THC and “without question” the hottest product to come out in the last year in Colorado’s blazing-hot marijuana industry. The crystals, which sell for more than $200 per gram in recreational dispensaries, are made using a complex soup of chemicals and solvents, including sephadex-LH20, dichloromethane, chloroform, acetic acid, methanol, hexane, and pentane, according to online instructions. The production process is still being ironed out. A state inspector recently became ill after a routine facility site visit, apparently from inhaling toxic fumes produced by a faulty crystal-making experiment.

Just a month prior, the fire department had no idea these crystalline products existed or how they were created, Rudolph said. Until more is learned about the products, inspectors observing facilities making crystals will issue cease-and-desist orders.

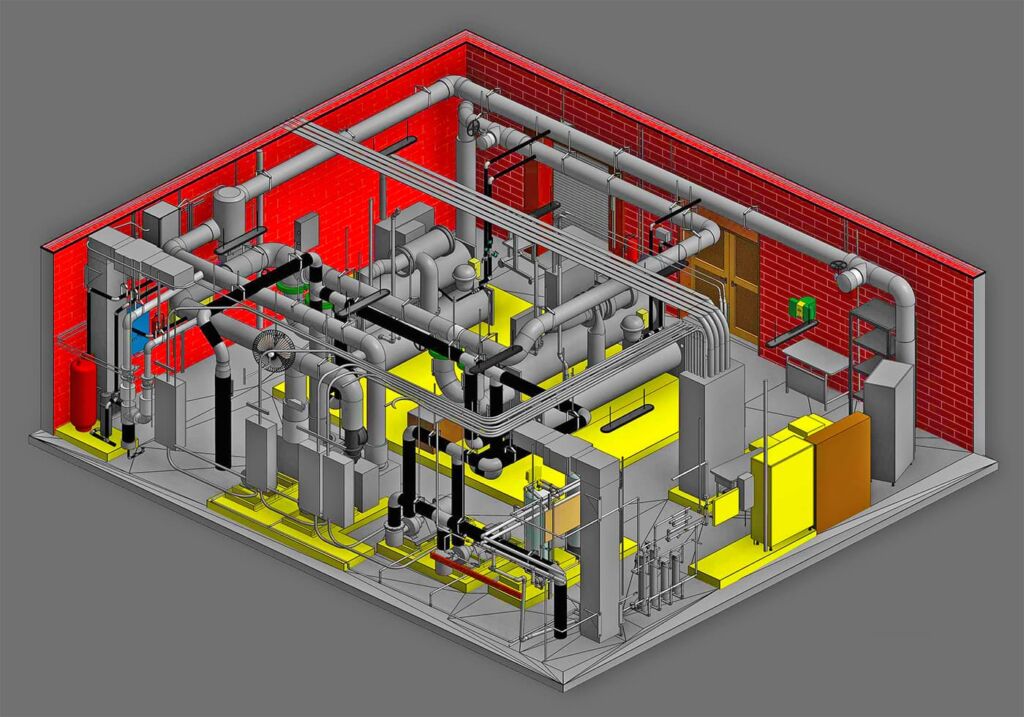

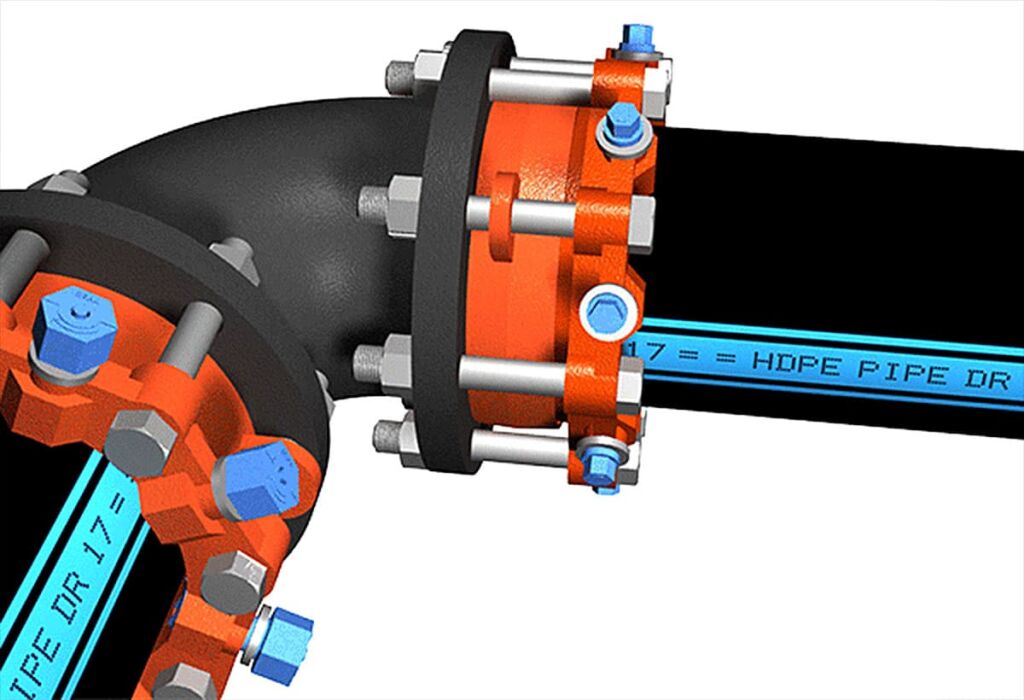

Next, we visit Mary’s Medicinals, which uses isopropyl alcohol as the solvent in its extractions, and then a company called Better Concentrates, which uses propane and butane. In both facilities, the workspaces resemble university chemistry labs. Each contains sophisticated instruments to test purity and to separate cannabinoids, terpenes, and other compounds from the concentrates based on the components’ boiling points and densities. At Better Concentrates, two professionally designed, peer-reviewed, closed-loop hydrocarbon extractors sit inside a special room within the extraction room, where large compressors circulate the air. Everything is grounded with wiring, and every piece of equipment is specially rated for use around flammable gases. Gas readers constantly monitor the air, and alarms sound if anything dangerous is detected.

“It’s a completely different world now,” said owner Dustin Mahon, who started extracting marijuana by blowing cans of butane through a glass tube in his backyard, a do-it-yourself manufacturing method that resulted in multiple deaths and injuries around the world and has since been outlawed. “It went from the Wild West to being the most regulated industry, I believe, in the state, if not the country.”

Both Better Concentrates and Mary’s Medicinals are clean, apparently well-run facilities that have good relationships with the Denver Fire Department, which is why, I ascertain, my hosts chose them to visit. I ask if other manufacturers are as diligent about safety and about following Denver’s strict regulations. Not necessarily, Rudolph said.

“Five years in and we’re still seeing some of the same problems,” he said. A common issue is marijuana business owners making building alterations, such as putting up additional walls or adding foam insulation, without pulling permits. Inspectors still regularly encounter facilities experimenting with solvents or processes that haven’t been approved by the city or state. Rudolph told me he sometimes thinks, partly in jest, that since the industry has been made legal, manufacturers come up with ways of doing things illegally “just so it will be fun again.”

Because of these issues, every firefighter and fire marshal I spoke to in Colorado and elsewhere about the pot industry has reiterated how important it is for inspectors and firefighters to get into facilities early and often, and to ask a lot of questions. Denver Fire inspects each marijuana facility twice per year. “So much is changing, we don’t have a choice,” Rudolph said.

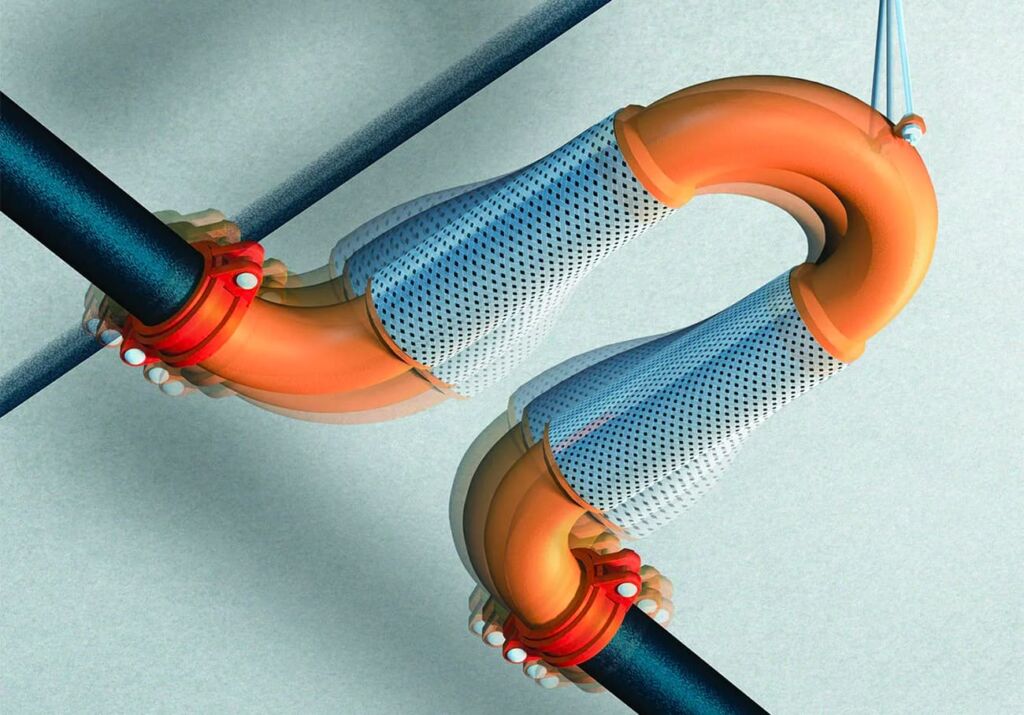

Those rapid changes also include the processing equipment used by the industry, which is nearly as competitive a market as the marijuana products themselves. Our tour includes a company called ExtractionTek Solutions, a leading maker of machines for hydrocarbon marijuana extraction. When I visited in 2015, ExtractionTek’s machines were comprised of a single-column, closed-loop system. As with all approved machines, the column was filled with marijuana flower, and a solvent such as butane, propane, or a combination of the two was cycled from a tank through the column, extracting the THC, and then back into the tank. Now ExtractionTek sells machines that are much larger and more expensive—an extractor can cost more than $100,000 with add-ons. The typical machine consists of three fatter extraction vessels that can each process six pounds of marijuana one after another without stopping, dramatically increasing the output of concentrate. In total, the machine can process more than 200 pounds of marijuana flower a day. Some facilities in California employ double shifts to process more.

Matt Ellis, the company’s owner and founder, says the evolution of the machines is based on processors’ demand. “We’re going for more efficiency and turnover, being able to reset faster,” Ellis told me. Manufacturers, he added, “are all looking for us to build bigger machines.”

As ExtractionTek’s market expands with legalization, revenues have jumped from $1.8 million in 2015 to about $8 million last year, according to Sean Winfield, the company’s chief marketing officer. Since sales of the machines are contingent on clients receiving permission from local agencies to build a facility and install them, the number of fire and building officials that need to be educated about the process has grown, too.

“I basically interview the regulators at the beginning of the process to see how much they know, for lack of a better description,” Winfield said. “It all really depends on the market. It can be a totally different story from one to another.”

Rules and regulations between jurisdictions can be all over the map as well. “I deal with most regions of the country on a county-by-county level, and there is an utter lack of consistency,” Winfield added. “If there was an agreed-upon national standard for everyone to follow, you would give me 20 percent of my time back on a day-to-day basis.”

The search for expertise

In lieu of a standalone equipment standard, the industry currently relies on a small cadre of experts to set benchmarks for safety and efficiency. One of those experts is Chris Witherell, who co-founded a company called Pressure Safety Inspectors in 2014. The firm’s modest offices are located at the back of a small, well-manicured office park about a half-hour south of Denver. There is no sign above the door, no administrative assistant to greet visitors, and no indication whatsoever that Pressure Safety Inspectors is one of the most influential players in the nation’s cannabis industry.

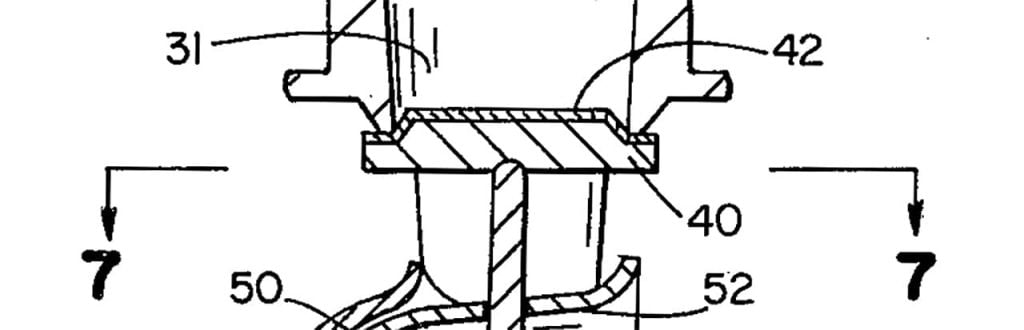

Few plans for marijuana extraction facilities or new equipment designs are approved in Denver—or in any other jurisdiction in the 15 states where the company is certified—without first crossing Witherell’s desk. A mechanical engineer who once made a living reviewing designs for highly customized nuclear energy equipment, Witherell now conducts independent review and verification of extraction equipment and facility design. As such, he wields the power in Denver and elsewhere to make or break a proposed project. This is true for two reasons: his engineering firm is one of the few nationwide willing or able to work in the marijuana space, and virtually none of the industry’s specialized processing equipment has undergone standardized testing or is listed by UL or other product safety firms. The lack of equipment safety standards means that Witherell’s professional judgment alone is usually the main deciding factor in whether a marijuana extractor or facility is deemed safe by regulators.

“The fire code says that you must use a piece of listed equipment or something else that is allowable,” Lukus told me. “Since none of it is listed, it comes down to the word ‘allowable.’ We require an engineer to write a report on the machine saying it is safe and then to go through the facility after it is inspected to give a report that it is safe.” The new marijuana facilities chapter in NFPA 1 also requires onsite inspections and peer reviews of equipment.

At least one equipment manufacturer I spoke with, who declined to have his name used, told me some in the cannabis industry view this requirement as a “cash grab” and likened it to “paying off” engineers in order to do business. Aside from the cost (equipment peer reviews cost between $10,000 and $20,000 depending on equipment complexity, Witherell told me), the manufacturer’s main gripe was his contention that engineers don’t know enough about his equipment to make the review worthwhile; he even suggested the industry could form a group to oppose it. Witherell said he’s heard these complaints before, but maintains that the onsite review is critical. “It’s a public welfare issue,” he said. “We’re doing engineering and making sure people don’t die. That’s what we’re supposed to do. I have no doubt in my mind that our reviews have made this equipment safer since 2014.”

As a result of his work, and the lack of competition, Witherell has seen more equipment designs and has likely been inside more marijuana extraction facilities than just about anyone else on the planet. In February alone, his firm submitted 42 separate proposals to conduct peer reviews, equipment inspections, or onsite facilities verifications. He or one of his employees is in perpetual motion from California to Maine, reviewing and signing off on marijuana facilities.

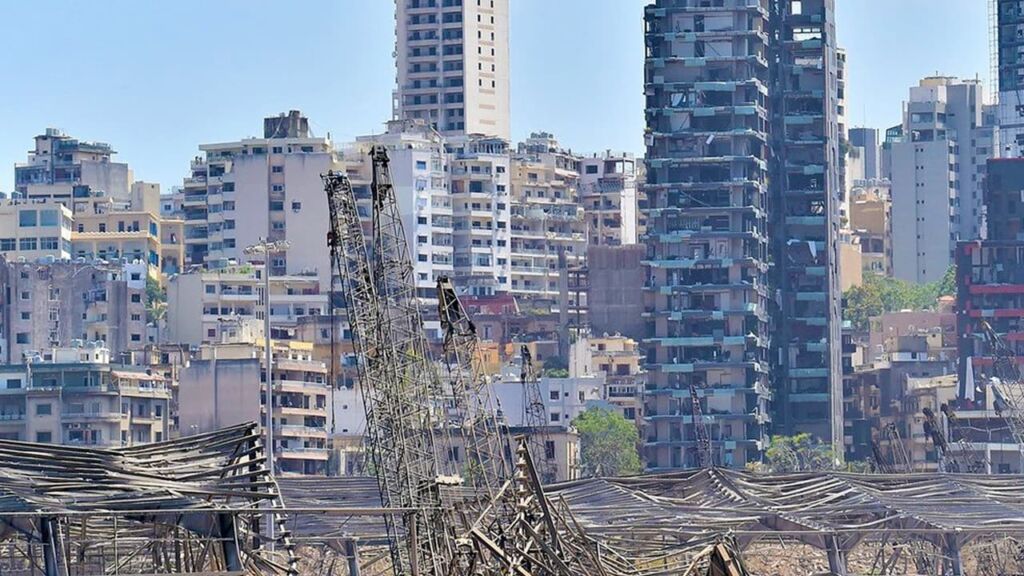

He’s witnessed a few horrors along the way. As we talk, Witherell clicks through photos on his computer, showing me shoddy setups rigged with off-brand parts and uselessly positioned airflow hoods. Some of the shots illustrate the consequences of these shortcuts. In one, a man is lying on a hospital bed with a 12-inch gash in his forehead, a wound he received when an extractor exploded and sent a metal plate flying in his direction, the result of improperly tightened valves. In another accident, two men were left with burns over 90 percent of their bodies after a gas leak sparked a fire. He plays me a grainy video of a woman in street clothes working on an extraction machine. The room she’s in looks more like a disheveled office than a processing facility. For no apparent reason, she turns away from the machine, and in that moment the extractor blows its top, sending a hunk of metal through the ceiling and releasing a cloud of propane gas into the room. The woman survived. “There aren’t many incidents, but when they do happen it is catastrophic,” he said.

Many of these events took place before 2014, when few rules and little oversight existed for marijuana facilities in Colorado. Facilities and equipment are much more sophisticated and safer now as the industry has matured, Witherell says. But some safety gaps and the potential for mishaps still remain.

One big problem, Witherell tells me, is the lack of proper equipment codes and standards for safety professionals to reference, and the open-to-interpretation nature of the job can lead to the approval of shoddy setups. More than once Witherell has walked into an extraction room and couldn’t believe an engineer had signed off on it. “I’ve seen certified equipment that has been stamped by another engineer that doesn’t even have an ASME-approved pressure vessel,” he said, referring to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, which approves components. “An equipment standard would benefit the industry, absolutely. We need a standard everyone can look to and say ‘this is how it needs to be,’ and there would be no question or room for interpretation. Now it’s totally left up to someone’s judgment.”

Other problems include a lack of skilled architects and engineers willing or able to work with the industry, as well as the marijuana industry’s own tendency to treat safety as an afterthought. Even well-informed facility owners often flunk his field verification inspection on the first try—“only 40 percent of the equipment we see in the field is 100 percent correct the first time,” he said.

In instances where Pressure Safety Inspectors is brought into the process late, or has been contracted to inspect an existing facility, serious problems can still exist, from extraction rooms that are poorly designed to mitigate the dangers of hazardous materials to facility owners who, maliciously or not, are a little too relaxed with equipment design and processes. Manufacturers with approved extractors purposefully alter them with components and add-ons from overseas, or even repurposed home brewing equipment, because they’ve read positive online reviews and want to give it a try in an effort to follow some new fad or just to experiment. In some cases, they use approved equipment in novel or unapproved ways, or unwittingly buy components from China with forged ASTM approved stamps, Witherell said.

When I visited in the spring, extracting under extreme cold was all the rage among Colorado’s marijuana concentrate manufacturers, who believe low temperatures produce a better product. Witherell says it’s typical for manufacturers to bring the solvent temperatures down to –90 degrees F, even though valves and components are only rated to –30 degrees F. “We walk in and the whole column has a big chunk of ice buildup around it,” which can cause the components to become brittle and vulnerable to failure, Witherell told me. “I’ve talked to a lot of equipment manufacturers and asked ‘does this make sense to you?’ They say no, but that’s what people want to do right now. Some guys swear by cold. It can be done, but you need the right equipment.”

He suspects that some marijuana processors will get sign-off from Pressure Safety Inspectors and then change things immediately. “That’s one reason I think an annual inspection is a good idea—but too few jurisdictions are doing that,” Witherell said. “It needs to be an engineer, or somebody who knows what they’re doing. I don’t think the average fire department has enough information.”

NFPA and the role of standards

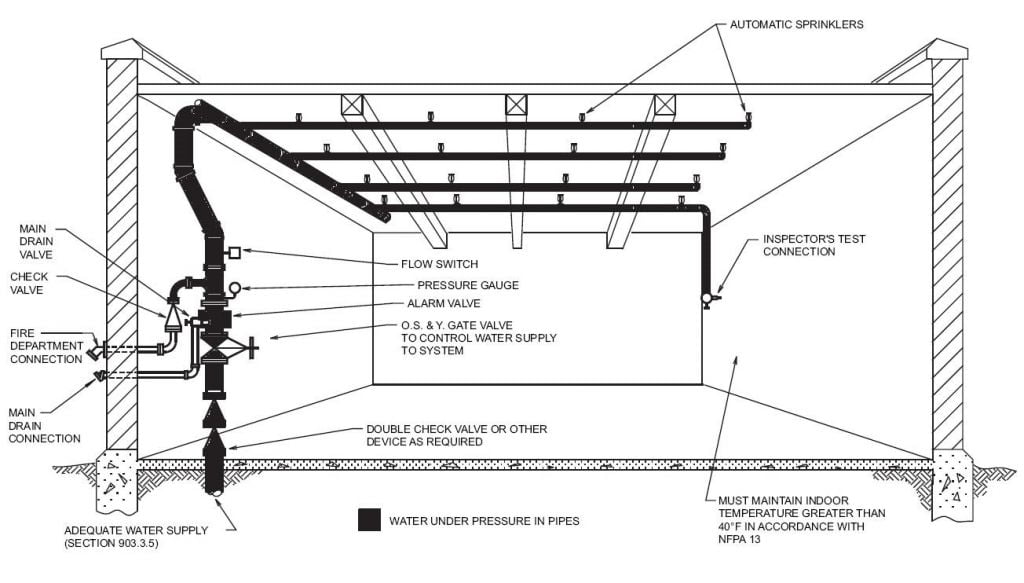

That need for additional guidance is a common refrain among regulators and some manufacturers in the cannabis industry, and one that NFPA has responded to. In 2016, NFPA assembled industry experts to help develop a new chapter in NFPA 1 addressing the burgeoning marijuana industry. The result, Chapter 38, Marijuana Growing, Processing, or Extraction Facilities, is intended to help authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) navigate some of the more challenging aspects of the industry.

The chapter includes basic requirements for permitting facilities; guidance on grow operations and issues like fumigation, signage, temporary walls and tarps, pesticides, CO2 enrichment, and more; general requirements for extraction room setups; and requirements unique to different extraction methods and processes, including hydrocarbon, CO2, and flammable and combustible liquids extractions. The chapter also includes a sizable annex that offers guidance to AHJs on details that a peer-reviewed technical report for the equipment should contain, and how to verify that it is sufficient.

“The committee wrote this chapter with our end users, AHJs, in mind, so when they go into these facilities they know what to look for to stay safe,” said Kristin Bigda, the NFPA 1 staff liaison who helped shepherd the document.

Although the 2018 edition of NFPA 1 only came out last fall, Bigda said the marijuana chapter has already generated interest. She has fielded calls from regulators across the country asking about it—most want to know what occupancy to classify a marijuana facility—and increasingly from the media.

More importantly, the document is being used. Last December, just a few months after the new Fire Code was published, Michigan’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs enacted a set of emergency rules to govern the state’s new medical marijuana industry. Chief among the measures was that all marijuana facilities comply with the 2018 NFPA 1, and that a fire safety inspection officer may conduct inspections to ensure NFPA 1 compliance “at any reasonable time.”

The new document is also currently being used in Massachusetts as that state braces for its first retail marijuana shops to open on July 1, along with the increased number of processing and grow facilities that will likely result. Numerous projects are already underway in the state, including a marijuana grow, extraction, processing, and packaging facility south of Boston that could eventually expand to 1 million square feet.

The most recent version of NFPA 1, which includes the marijuana chapter, has not yet been adopted statewide in Massachusetts, but state rules allow local fire departments broad authority to apply special conditions to the building permit on projects that involve hazardous processes.

“One of the conditions we suggest to fire departments is that they require the use of the most recent edition of NFPA 1, which includes the marijuana facilities chapter,” said Jennifer Hoyt, the chief fire protection engineer at the Massachusetts Department of Fire Services. “We like NFPA 1 because there are a lot of safeguards in there that have been discussed and vetted on a national level. It makes sense to take from that national knowledge base rather than try to come up with something on our own.”

As in Colorado and other jurisdictions where marijuana has been legalized, regulators in Massachusetts have been forced to play catch-up. When medical marijuana dispensaries were approved in 2014, some grow and processing facilities were allowed to be built into retrofitted spaces in old mills and basements, which fire officials observe is neither ideal nor allowed under NFPA 1. But as the recreational marijuana industry takes off and facilities are approved, Hoyt believes the regulatory community is becoming more knowledgeable about how to go about assessing plans. Local jurisdictions have the ultimate authority in Massachusetts to approve plans, but the state’s Department of Fire Services is increasingly involved in helping. The intense media and public scrutiny that surrounds the industry has helped with oversight, Hoyt said.

“Whenever a facility is proposed, there is usually a huge town meeting—it’s very political, with a lot media attention. So the AHJs often come to us and ask what we know about this, because they know they are going to get a lot of questions,” she said. “We tell them to adopt NFPA 1, because it’s the newest and best thing out there to regulate processing.”

Hoyt’s department has developed an approval checklist for AHJs, which includes conditioning permit approval on compliance with the 2018 NFPA 1, as well as steps such as installing CO2 monitoring and developing emergency plans. “We go through the checklist with them. When a facility goes up, we want to hold everyone to the same standard, even though it is regulated on a local level,” she said.

Mahon, owner of Better Concentrates in Denver, is also strongly in favor of a common set of safety regulations to govern the industry, a sentiment Lukus has also heard from other manufacturers. Part of the reason manufacturers are willing to tolerate regulation, Mahon says, is the looming threat that the federal government, which still prohibits marijuana, will begin prosecuting manufacturers—nobody wants an explosion or significant incident to give the government a reason to clamp down.

Another argument for regulation is simple economics. “I can count 12 different companies that moved from Denver to get away from the safety regulations that we have embraced,” Mahon said. “We often feel like we play with our hands tied behind our backs because we try to be as compliant as possible. The other players that don’t comply get an advantage, and that doesn’t seem quite fair.”

Regulators and manufacturers also agree on another point: as the marijuana industry steps out of prohibition and establishes itself as a legitimate economic power, there will be many more changes before some kind of stasis is reached. Pot research, suppressed for decades by federal law, is just now starting to blossom, fueled by billions of dollars in investment. So far, an industry behemoth—the Budweiser of the bud business, as it were—has yet to emerge, though big pharmaceutical companies and investment banks are beginning to gingerly dip their toes into the cash pool. “I have no doubt that big agriculture, big food, big pharmaceutical, big alcohol, and big tobacco will jump into this space as soon as they are allowed,” Mehta, the cannabis investor, told his audience at the Cannabis World Congress.

What that means, and what’s next, is anyone’s guess. What’s certain is that regulators and inspectors across North America will continue to have their hands full.

“It takes a while for fire departments to catch up on the learning curve whenever a new manufacturing process emerges,” Hoyt said. “But the fire service is very adaptable. Whatever is in our community, we deal with it.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.