Precision Fire Protection News

Nursing Home Retrofit – Lessons Learned

New requirements meant an older nursing home would need to retrofit a new sprinkler system to expand the coverage provided by an older sprinkler system. And a tight deadline meant new challenges for everybody.

BY ASHLEY SMITH

MARQUIS MT. TABOR IS A FIVE-STORY BRICK BUILDING on a hillside in a quiet neighborhood of Portland, Oregon. Built in 1922 as an Adventist hospital, the building was eventually repurposed as a nursing home and later sold to the Marquis Companies, which operates it today as a long-term care and rehabilitation facility. It is now home to about 100 acute-care patients, all of them elderly, and many disabled, injured, or ill.

The 110,000-square-foot Marquis Mt.Tabor building still looks much like a hospital from the outside. A U-shaped driveway in front leads to a covered entrance. Inside, a central corridor is flanked by two patient wings, extending to the east and west, with the main floor containing administrative offices, living room areas, and kitchen and dining facilities. Patient rooms are located on the upper floors.

Like many buildings its age, Marquis Mt. Tabor was built in an era when fire code and life safety standards were less stringent than those today. The building went through a major expansion and renovation in the 1960s, but, even then, sprinklers were only required in main corridors, not in patient bedrooms or bathrooms.

None of that presented a problem until Marquis Mt. Tabor administrators learned that the building’s sprinkler system would have to be updated and expanded.

In 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or CMS—the federal agency that administers both programs—had finalized a rule requiring nursing homes without sprinkler systems, or with inadequate systems, to retrofit. The CMS rule, which reflected changes made in the 2006 edition of NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, stipulated that the sprinkler upgrades be completed by August 13, 2013. Facilities that did not meet the deadline risked penalties from CMS, ranging from being issued violation notices to the eventual withholding of Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements for non-compliant facilities that exhibited serious or chronic violations. “That was a pretty good motivator,” said Kym Wells, Marquis Mt. Tabor’s administrator.

Expanding, modernizing or adding a sprinkler system can be a difficult project in any existing building. There are detailed designs and months of planning to be done. There are walls and ceilings to open, a process that often reveals other problems—such as the presence of asbestos—that have to be remedied. There is the months-long distraction of constant construction.

Marquis Mt. Tabor certainly wasn’t alone in those challenges, since nursing homes and long-term care facilities across the country faced identical requirements. But Marquis Mt. Tabor needed to complete the project on a tight deadline while continuing to care for elderly, sick, and injured patients as the sprinkler system was being installed. Moving the residents from the building was not an option, Wells said, and patient care had to remain the top priority.

According to people close to the project, Wells and the team she assembled provide a good model for how to plan and execute a sprinkler retrofit in a functioning health care facility. “Marquis did it right,” said Dale Groshong, project manager for Portland-based Basic Fire Protection, Inc., the company that designed and installed the sprinkler system. Groshong, who has worked on hospital and nursing home sprinkler projects since the 1980s, said Marquis Mt. Tabor took a number of steps that brought efficiencies to the entire retrofit process while keeping patient and resident care its top priority.

Examples like Marquis Mt. Tabor might even serve as models for hospitals, the next large category of health care facilities that could be required to retrofit sprinkler systems. No such requirements currently exist, but NFPA 101 technical committees will likely revisit the possibility next year when they begin deliberations on the 2018 edition of the Life Safety Code.

The CMS rule on nursing home sprinklers—the result of extensive public comment, followed by a five-year compliance period—gave hospitals plenty of opportunities to observe how it’s done, said Chad Beebe, deputy executive director of advocacy for the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) of the American Hospital Association. “We’re afforded the availability to see what’s coming in the future,” Beebe said. “It’s the best crystal ball we can have.”

The planning process

Don Pfaff’s daughter was born in the Marquis Mt. Tabor building in 1978, when it operated as the Portland Adventist Hospital. Thirty-four years later, he walked through the doors for a very different purpose: to evaluate the existing sprinkler system.

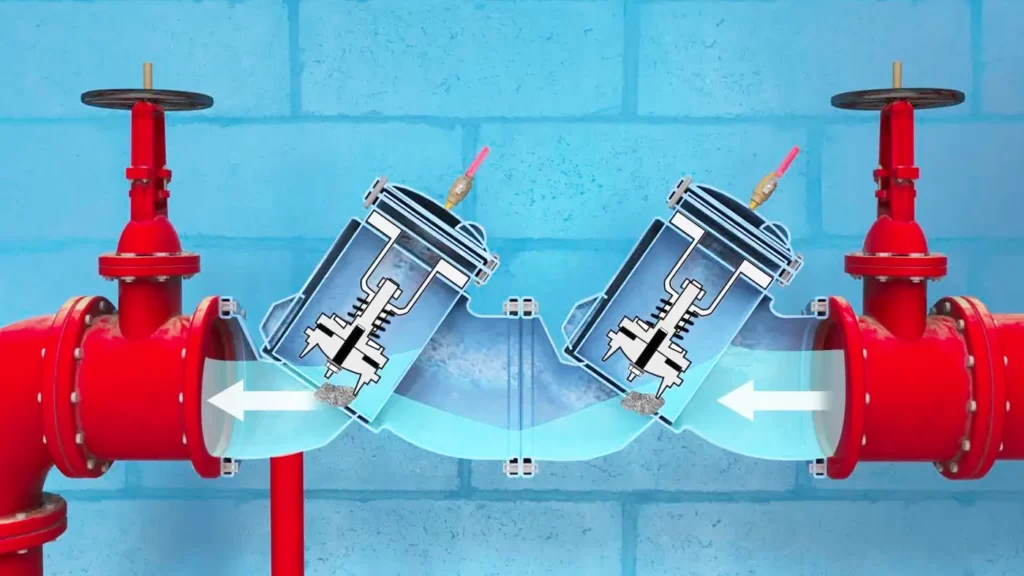

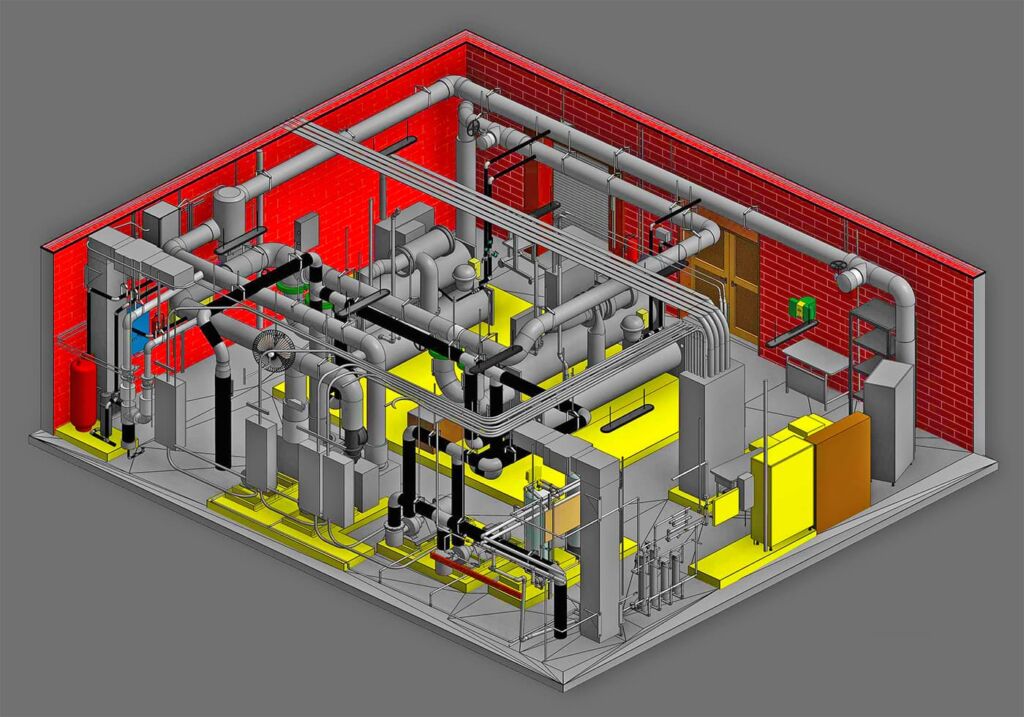

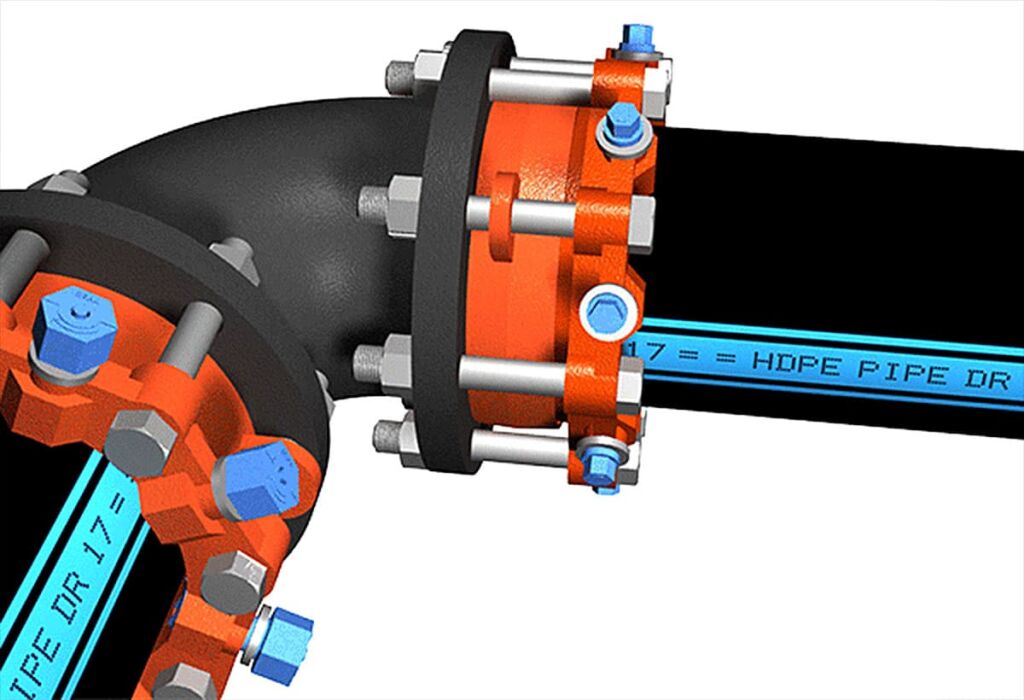

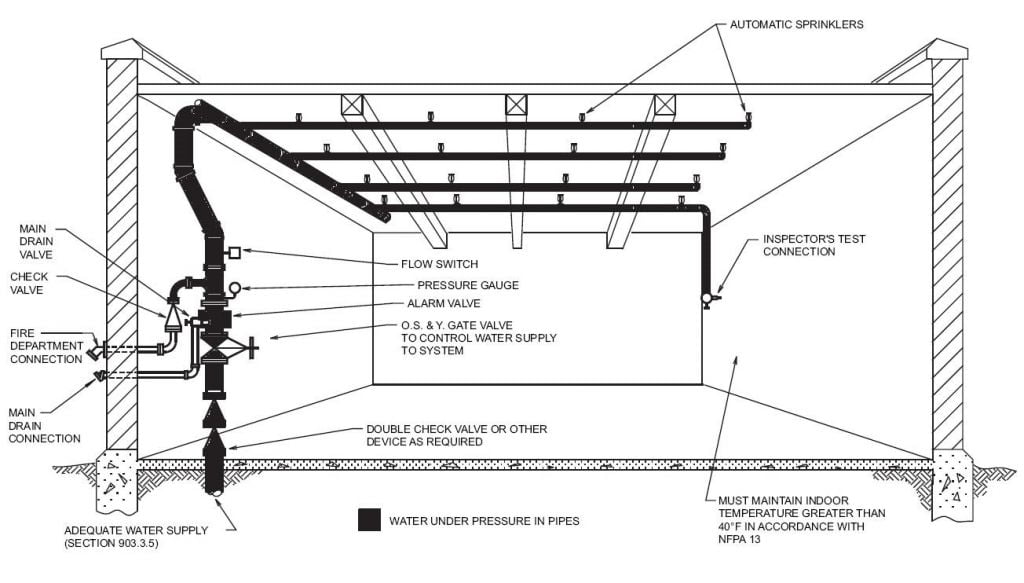

The wet pipe sprinkler system covering the main corridors was in good condition for its age, said Pfaff, but there were not enough sprinklers, nor were they in all the required places, such as bedrooms and bathrooms. “The system was old, but adequate,” said Pfaff, an associate and senior mechanical engineer with R&W Engineering, a Beaverton, Oregon-based firm that conducted design engineering work and completed a scope-of-work document for the Marquis Mt. Tabor retrofit project. “The piping had been installed per code at the time it was put in, and it wasn’t leaking. But it didn’t cover or protect the whole building.”

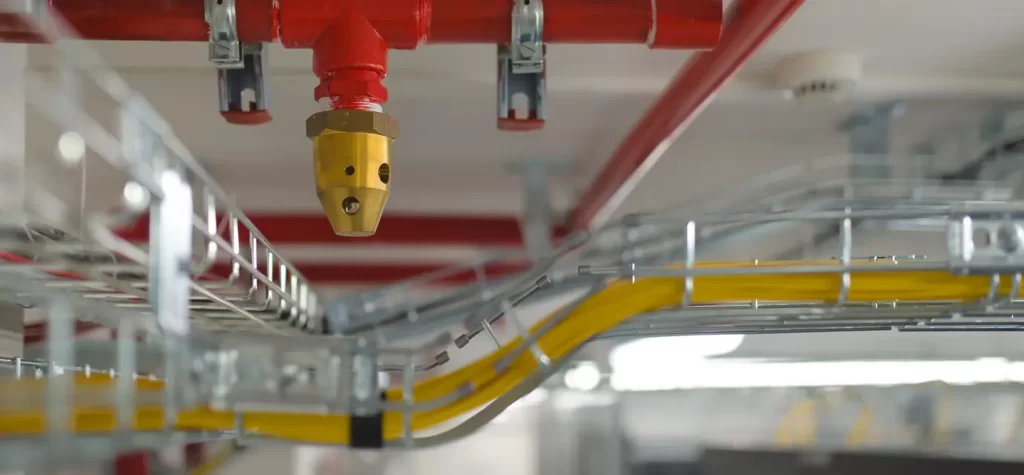

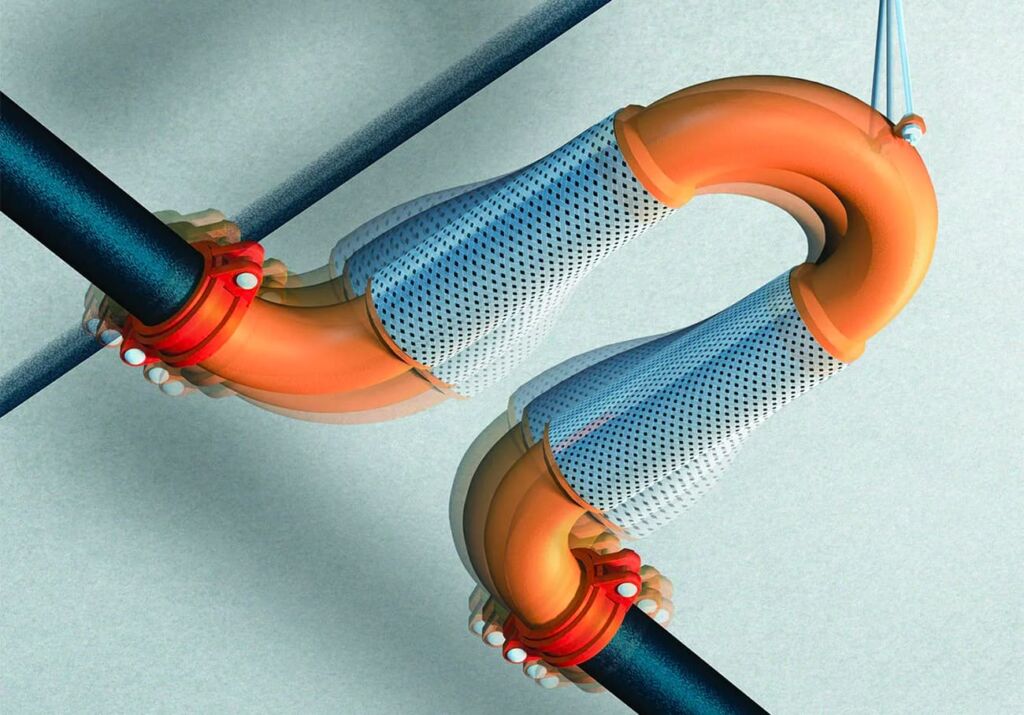

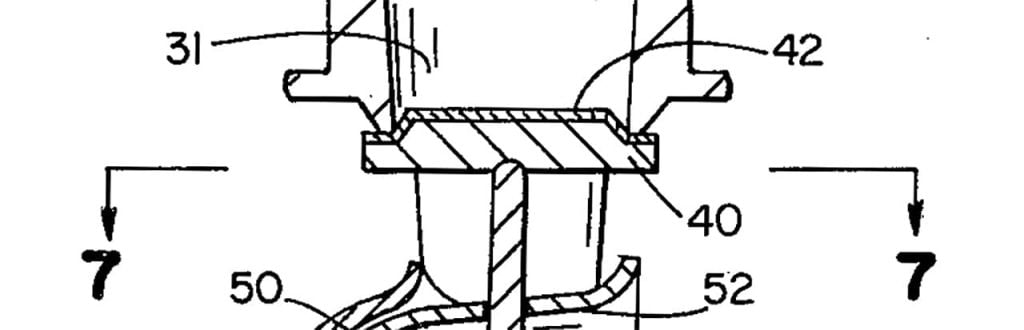

To achieve adequate coverage according to CMS requirements, NFPA 101, and NFPA 13, Installation of Sprinkler Systems, Mt. Tabor needed to add 266 sprinklers to 69 patient rooms, 69 bathrooms, and six shower rooms. The extension consisted of a wet pipe system, the most basic, least expensive, and most common type of system. Groshong estimates that 99 percent of the sprinkler systems his company installs are wet pipe systems.

There were an assortment of structural challenges associated with the retrofit. More than 90 percent of the rooms had asbestos in the ceiling, so abatement would have to take place along with the sprinkler installation, Wells said. There was also the issue of holes in the walls and ceilings during construction, which is a major concern for nursing homes because such penetrations present a clear avenue for fire and smoke movement, she said. And the timeline was tight. By the time the project was planned and went out to bid, in March of 2013, the CMS deadline was just five months away. Marquis Mt. Tabor wasn’t alone in waiting until the last minute to make the upgrades; according to CMS information, nearly 1,300 nursing home facilities nationwide were not fully sprinklered as of June 2013.

The logistical challenges were many and complex. Where would patients go when their rooms were under construction? How would staff ensure that displaced patients received the proper medication and food? The staff, Wells said, was concerned with all aspects of the patients’ health and safety. They were also concerned about the psychological impacts of the disruption, particularly for patients with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. All of Marquis Mt. Tabor’s 100 patients would have to be moved at some point during the project.

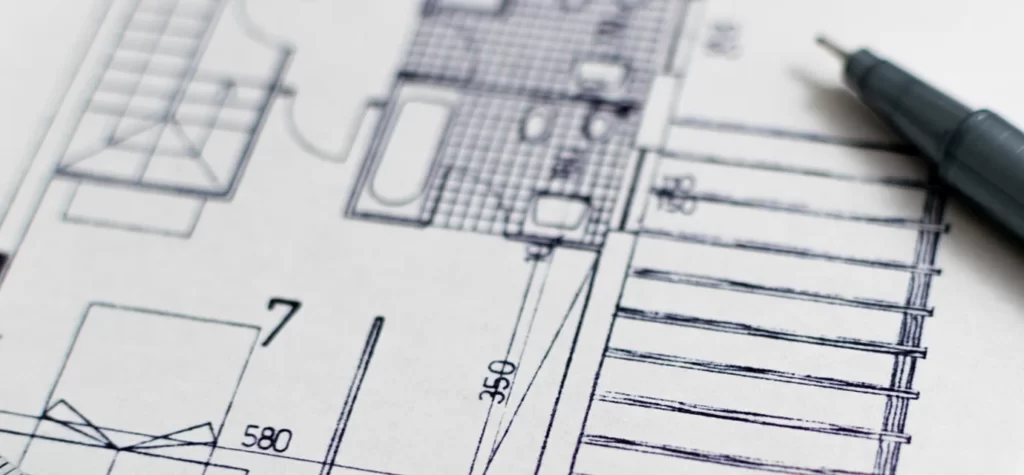

From the beginning, Wells said, she knew that focused and detailed preplanning would be the key to pulling off this project on time and with the least amount of disruption to patients. After meeting with her director and vice president of operations in November of 2012 to let them know the project was imminent, Wells’ first step was meeting with Pfaff’s company—which she had worked with before on a heating/ventilating/air-conditioning project—to have them assemble a detailed scope of work for the project.

That is an unusual step for sprinkler installation projects, according to Groshong, who said most nursing homes simply put the project out to bid and let the installer handle all the details from there. “I work with a lot of other people on these projects I lay the project out and provide all documentation, and they just trust me,” he said. “In this instance, Marquis hired a design engineer to come up with specs, drawings, and criteria for access [to the existing sprinkler system] so they could provide that information to bidders.”

Wells said she wanted to make sure any installer who bid on the project knew exactly what they would face when ceilings and walls were opened up. Pfaff agreed, and his company spent about six weeks reviewing the existing sprinkler system and putting together complete documents outlining the scope of work required. R&W, at Wells’ request, also put together the request for proposal, or RFP.

Wells also hired a general contractor, Portland-based Construction Management Group, Inc., to deal with day-to-day issues that arose, which is a more common step. But, unlike most nursing homes, she didn’t leave the job entirely in the company’s hands. She used her own, independent maintenance contractor to open up the walls and ceilings for installation, and to patch them later. She used her own housekeeping staff to clean the rooms when the work was complete.

All of this led to substantial cost savings, said Groshong. The engineering work allowed the installer to bid on and complete the work with no surprises. Using some Marquis Mt. Tabor resources, as well as independent contractors she had worked with in the past, helped Wells save on the total bill. The entire project cost $195,875, and more than half of that was for asbestos abatement alone. The engineering costs were $27,350 and the design and installation costs were $64,376.

By industry standards, that is very low, Groshang said. “They did everything right that allowed them to be cost effective,” he said. “I haven’t seen that in the last 30 years in this business.”

The final planning step was figuring out how to manage and move patients during construction. Wells petitioned the state for permission to use small dining rooms as temporary patient rooms during construction, part of her effort to limit the number of rooms taken out of service at once. The state agreed to Wells’ request. Marquis Mt. Tabor decided to keep patients with their assigned nurses, even if patients were temporarily moved to another floor, to avoid medication mix-ups. Wells created a precise written schedule that detailed which rooms would be updated when, and where the patients would go. Wells instructed her staff on exactly how the project would go. The project would start in March, and Wells was determined that it would be finished by July 13—a month ahead of the CMS deadline.

The construction

Armed with the scoping documents prepared by R&W Engineering, the project’s winning bidder, Basic Fire Protection, spent about two weeks designing the new sprinkler system, Groshong said. The work was designed to meet the requirements of NFPA 13. While NFPA 101 includes the general rule requiring existing nursing homes to retrofit, it does not discuss how to go about it; NFPA 13 sets specific minimum design and installation requirements.

The project involved extending all the existing steel sprinkler piping in the central corridors into bedrooms and bathrooms, then adding sprinklers in those bedrooms and bathrooms. In a rare stroke of luck, Groshong said, the original sprinkler system had been designed to allow for future expansion—something that is almost unheard of, even today. “We kept looking at the design and saying, ‘Nobody did this then. Nobody does this now.’ We couldn’t believe it,” he said. “Typically, every sprinkler system is designed to the minimum required standards.”

The project started in an unoccupied wing of the building. The facility is licensed for 145 patients, but housed about 100 at the time. However, using the empty wing to house patients during construction was not an option, according to Wells, because all the heating components in the rooms had been removed for eventual replacement.

Two rooms were prepared at a time, and those patients were moved to the temporary rooms. The work lasted from one to four days per room, depending on the size of the room and whether asbestos was present. Walls and ceilings were opened, and the new sprinklers and piping were installed. Asbestos was removed by a separate company, Portland-based PBS Engineering + Environmental. Finally, the walls and ceilings were closed and the housekeeping staff was brought in to clean the rooms.

The project was not without its setbacks. The precise schedule laid out in advance did not always work, Wells said. There were times where patients were sick and could not be moved from their rooms, and last-minute decisions had to be made to move on to the next scheduled room and circle back later. “It required my entire team, every day, to coordinate moving these patients around,” Wells said.

There was also a blip with the Portland Fire Marshal’s Office. The Oregon State Fire Marshal’s Office, the authority having jurisdiction, had approved the project plans, Wells said, but when local officials found out about the project, they wanted to inspect every installation—all 266 new sprinklers and corresponding piping—before the ceilings and walls were closed. That would have meant walls and ceilings would have to remain open for seven to 10 days until an inspector could arrive.

“I said, ‘Oh, no, we need to move forward,’” Wells said. “I told them we had a deadline, that we couldn’t keep those penetrations open, and I asked them if they could come and do those inspections daily.” Wells said she worked out a deal where the local fire marshal’s office visited the site twice a week to inspect the work as it progressed.

Although nursing homes across the country faced the same challenge and time constraints as Marquis Mt. Tabor, this type of project was rare in Oregon. According to Stacy Warner, former assistant chief deputy and fire and life safety branch manager for the Oregon Office of State Fire Marshal, most of the state’s existing nursing homes were already fully sprinklered because they’d been built later than the Marquis Mt. Tabor building. Because such buildings on the West Coast tend to be newer, Warner said, Marquis Mt. Tabor was one of “two or three facilities in the state” that had to retrofit or upgrade sprinkler systems.

The final sprinkler was installed in mid-July, Wells said. The final inspection and approval by the city fire marshal came July 24, and the state fire marshal approved the project following a July 31 inspection, Wells said. The state fire marshal then put together its written report on the approval and notified Mt. Tabor’s licensing board, the Oregon Nursing Home Administrators Board, that the facility was in compliance.

Looking forward

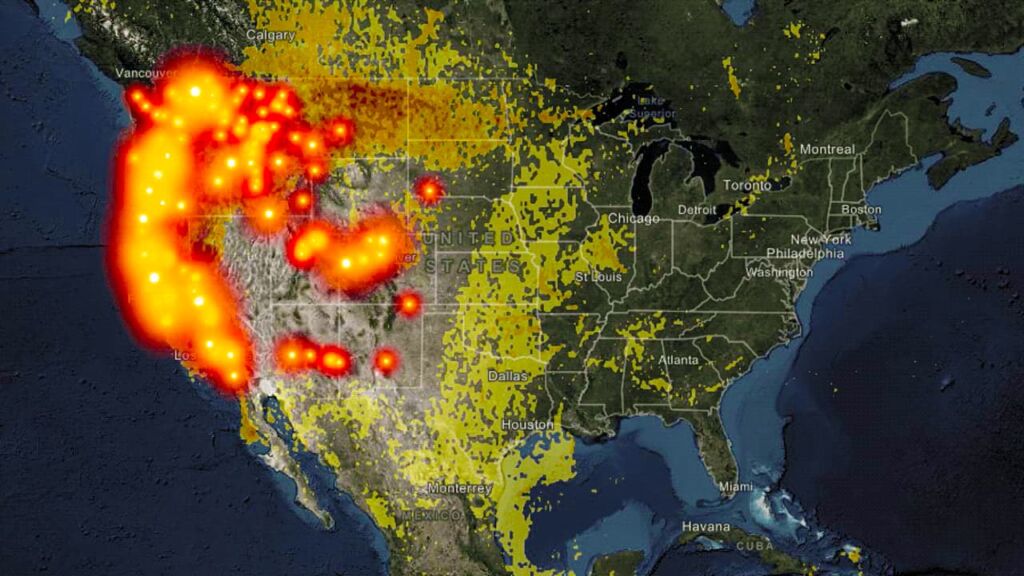

As a result of its deadline for sprinkler compliance, CMS estimates that 97 percent of nursing homes in the United States now have updated or newly installed sprinkler systems—though it also points out that more than 380 nursing homes, housing more than 52,000 people in 39 states, still are not fully sprinklered, and that some of those have no sprinklers at all.

As an example of how to do a retrofit—and, more specifically, planning and managing a complex sprinkler installation project with a building full of patients—Marquis Mt. Tabor may serve as a model for an important group of health care facilities facing sprinkler requirements: hospitals. Currently, only new hospitals are required to install sprinkler systems in accordance with NFPA 101, which is one of the conditions they must meet to receive CMS reimbursement; existing hospitals do not have a blanket requirement in NFPA 101 as nursing homes do to install new sprinkler systems or update existing systems. Systems are installed in existing hospitals when floors are reconfigured or remodeled. But the question of requiring existing hospitals to simply install sprinklers has already been debated by NFPA 101 technical committees, and is expected to come up again next year when the committees meet to begin work on processing the 2018 edition of the code, said Robert Solomon, NFPA’s division manager of Building Fire Protection and Life Safety.

Proponents argue that they shouldn’t wait for a devastating fire to require hospitals to be fully sprinklered, Solomon said, but there also hasn’t been a major hospital fire in the U.S. in a long time. And many, though not all, hospitals have decided on their own to upgrade sprinkler systems when they renovate, he said. Even so, “the issue always comes up with our NFPA committee,” Solomon said. “The question is, should we just have the same blanket requirements that we put in place for nursing homes?”

The lack of major hospital fires in recent memory may partially be the result of higher staffing levels in hospitals compared to nursing homes, Solomon said, which means more people to respond in emergencies. Coupled with strictly enforced no-smoking policies in hospitals and ongoing inspection, testing, and maintenance programs for fire safety and medical equipment, these all add up to offer a safe environment for patients, visitors, and staff.

In general, incidences of hospital fires in the U.S. have dramatically declined over the last few decades, NFPA data shows. There were 1,110 fires reported in 2011, the most recent year for which data has been published. That was the lowest number since 1980, when 8,330 hospital fires were reported. The number fell below 5,000 for the first time in 1986; below 3,000 in 1990; and below 2,000 in 1995. In the U.S., less than one death per year, on average, is caused by hospital fires, according to NFPA data.

No public data exists on the percentage of hospitals in the U.S. that have code-compliant automatic sprinkler systems. Of the reported structure fires in hospitals from 2007 to 2011, 63 percent of those hospitals had sprinklers, according to NFPA data published in 2013.

Beebe, of the American Society for Healthcare Engineering, said he believes hospitals, for the most part, would not be resistant to retrofitting, even though there would be challenges similar to what nursing homes faced. Patient care would have to come first, he said, and hospitals could not turn patients away in the midst of a sprinkler upgrade. There are certain rooms that would be difficult to take out of service to complete these projects, such as operating rooms and labs, he said. As with nursing homes, asbestos would likely have to be removed from many older buildings, he said.

For hospitals, Beebe advises starting sprinkler retrofit projects well before any deadline is imposed. That’s not just because of the logistical issues, but because patient safety could be at risk. But the effort would be well worth it, he said. “[Sprinklers] afford us the time we need to deal with patients in an evacuation. They’re very critical,” he said. “It has been proven over time that sprinklers save lives.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.