Precision Fire Protection News

The EMS Revolution – Home Based Care

New models of home-based care hold promise to help fix a broken EMS system—and keep people with chronic ailments out of the emergency room

BY JESSE ROMAN

KELLY ABBOTT SPENDS MOST DAYS in a car, crisscrossing San Antonio’s 465 square miles to visit the homes of some of the sickest and most desperate people in the city. Some are mentally ill, like the guy who compulsively swallows metal objects; others are addicted to drugs; most face a long list of challenging maladies. All of them, for one reason or another, seem to find themselves in the back of an ambulance a lot—in some cases, dozens of times a year.

As one of 10 medics on the San Antonio Fire Department’s Mobile Integrated Health Care unit (MIH), Abbott’s mission is to try and help these patients break their dependence on 911 by better managing their health—for their sake and for the sake of SAFD’s overworked EMS units.

On an overcast afternoon last March, Abbott took me on a ride to show me how he does it. We made our way through a particularly downtrodden San Antonio neighborhood, passing rows of small weathered houses with cluttered yards. As we approached our destination, a small blue house with peeling white trim and a rusting tin roof, Abbott told me about the patient we were visiting, a 40-year-old woman I’ll call Tammy.

“She was a train wreck when I met her,” said Abbott (pictured below), a gregarious man in his mid 40s. Most of Tammy’s many ailments stemmed from complications related to diabetes, including kidney failure, infections, amputations, and congestive heart failure. Her latest stint in the hospital, however, had been with a bout of pneumonia—at least the 20th time she’d been hospitalized with the respiratory infection.

Despite the setback, Abbott was hopeful—Tammy, the mother a young child, was actually doing a lot better than when he first knocked on her door several months earlier. Thanks to his help, she was seeing a doctor regularly, was taking a new and more effective insulin, and had managed to keep her conditions relatively under control for the first time in years. She had required far fewer ambulance trips with San Antonio Fire EMS.

SAFD set up the MIH program in 2016 specifically to address patients like Tammy. Functioning as a mix of mobile hospital, social work organization, and detective agency, the goal of San Antonio’s MIH is to find the root cause of why the city’s “high-utilizers” call 911 so often, and to work with them, their doctors, and community aid organizations to help them become healthier and less dependent on emergency transport. In just under four years, the program has already saved the department thousands of would-be ambulance transports, and millions of dollars.

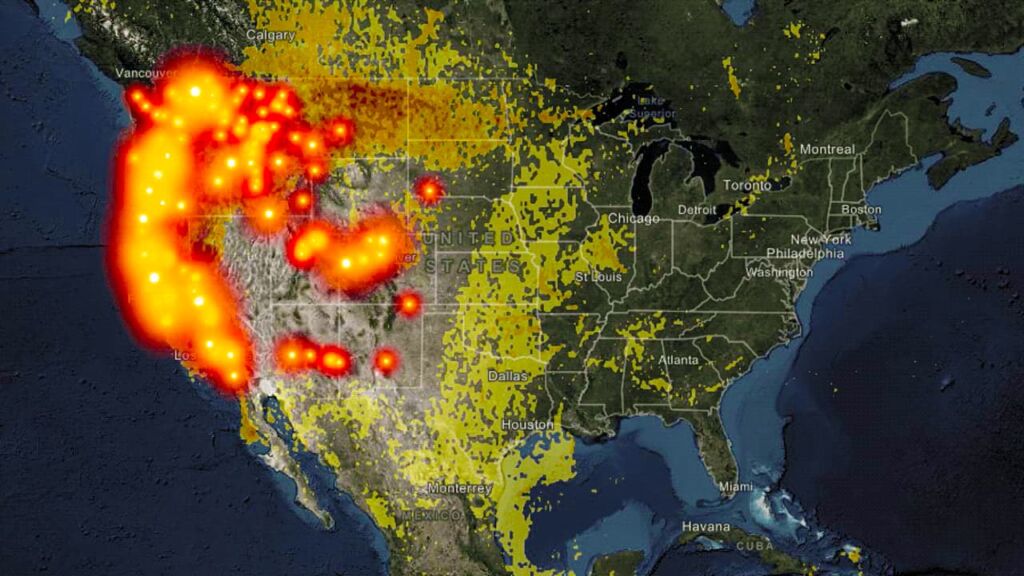

This proactive approach to EMS is one of numerous examples of mobile integrated health care programs (also known as community paramedicine) that have taken root across the United States in recent years. A 2018 survey conducted by the National Association of EMTs (NAEMT) found that more than 200 EMS systems across the country are now doing some form of MIH; a decade ago, there were only four. The growth is only expected to continue.

Last summer, NFPA published a new document to help facilitate that expansion. NFPA 451, Guide for Community Health Care Programs, lays out the considerations for EMS agencies that want to build an MIH or community paramedicine program from scratch. The guide was developed by technical expert volunteers, many of whom have already built successful programs, made mistakes, and gained key insights along the way (see “Lessons Learned”).

While the details of specific MIH programs can differ widely from system to system, the overall concept is usually the same: instead of reflexively taking every patient who calls 911 to the emergency room—as EMS has done almost exclusively for decades—agencies are now exploring a range of other options. These include treating patients at home, transporting them to alternate destinations like a doctor’s office or urgent care, or even, as with SAFD, forming relationships with certain high utilizers to understand the underlying causes of their chronic medical issues and to try to fix, or at least manage, those causes.

EMS agencies that have rolled out MIH programs have seen dramatic results, including a drop in 911 calls, increased revenues, happier patients, and reduced overall health care spending. As a result, hospitals, private insurers, and even the federal government have begun, for the first time, to pay EMS providers to treat patients using these less-costly alternatives.

In early 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced a new five-year pilot program called the ET3 model—short for emergency triage, treat, and transport—where the federal government will for the first time pay participating EMS agencies to bring patients to alternative destinations besides the ER, as well as to treat patients at home, either in person or over the phone. The program also encourages local governments and other entities that operate 911 dispatches to establish a separate medical triage line for 911 calls from low-acuity patients—that is, patients who require less-intensive care for their ailments, such as chronic, non-life-threatening conditions. Several states have also recently passed laws to allow EMS more flexibility to be paid for treating patients at home, and utilizing other options outside of the ER.

According to EMS leaders and health care officials I spoke with, the evidence suggests that we could be on the brink of a dramatic shift in how health care is delivered in the United States. Many think that MIH will soon be a ubiquitous part of the daily function of EMS and fire-based EMS nationwide.

“Much like EMS was the future of the fire service in 1997, mobile integrated health care is the future of EMS in 2020,” said Matt Zavadsky, president of NAEMT and an executive at MedStar Mobile Healthcare in Fort Worth, Texas. “Cities have a standing army of health care professionals who just happen to be in fire stations. Instead of going out and preventing fires, they are out there preventing 911 calls.”

FOLLOWING THE MONEY

Despite her recent travails, Tammy offers a weary smile when she sees Abbott at her door. He makes her laugh with a few jokes and encouraging words before taking Tammy’s vitals. He asks about her blood sugar, and they chat about the medicines she’s been prescribed. They discuss her upcoming follow-up appointments with a specialist, and Abbott writes out a couple of taxi vouchers that she can use the next day to get to and from her doctor’s office. In less than 10 minutes, we’re out the door.

The visit I witnessed was a sharp contrast to how EMS has historically dealt with chronically sick patients. Since modern EMS began in the 1970s, the famous motto for most ambulance companies has been “you call, we haul”—meaning if you call 911 for any reason, they’ll give you a ride to the emergency room. In fact, in most cases the ambulance ride continues to be the only thing that insurers pay EMS to do.

For many years, this financial arrangement—“bring patients to the hospital, or don’t get paid”—has led to a predictable outcome: no matter how minor a patient’s ailment, almost anybody who calls 911 for a medical situation is brought straight to a hospital emergency department, even when another approach would almost certainly be better for everyone. In the last decade, however, strong economic forces throughout the health care industry have slowly begun to reshape this inefficient and expensive system. “The reality is that all of this transformation of EMS into something other than ‘You call, we haul’ is about the money,” Zavadsky said.

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, hospitals have been financially incentivized to reduce their patient readmissions rates. If the same person is readmitted to the hospital for a cause that is deemed preventable by Medicare and Medicaid, the hospital isn’t paid and can be fined. At the same time, insurers are unnecessarily spending billions of dollars on frivolous and preventable ER trips when lower-cost home visits from a nurse or skilled paramedic would be more effective. For those and other reasons, most health professionals now acknowledge that it’s a lot cheaper and just as effective to treat low-acuity patients at home or at a doctor’s office rather than an emergency room.

A community paramedic from MedStar assesses a patient at her home as part of the organization’s readmission prevention program. (Courtesy of MedStar Mobile Health Care)

Meanwhile, EMS systems across the country are on the brink of collapse. Local news stories from Toledo to San Diego tell of overworked and underfunded EMS agencies buried under an ever-increasing volume of 911 calls. According to a recent article in EMS World, it’s not uncommon in some understaffed agencies for a single ambulance to make 20 or more runs per day, causing crews to work almost nonstop during a 24-hour shift. To add insult to injury, many of these EMS systems are barely financially viable.

Before launching its MIH program in 2009, MedStar was sending an ambulance to every call, even for something as benign as a patient with foot blisters, said Zavadsky, MedStar’s chief strategic integration officer. “And we were rarely, if ever, getting paid for those services because they didn’t meet medical necessity for an ambulance,” he said. “We were eating those costs.”

Out of pure self-preservation, EMS agencies have been forced to find another way. “Our health care system is bankrupting our country, our public service budgets, and our public safety budgets,” Zavadsky said. “EMS providers across the country need to figure out, in an economically finite world, how we can bring more value in order for us to maintain relevance.”

BENDING THE CALL

VOLUME CURVE

All of those factors were in play in 2014 when SAFD began exploring ways to manage its way out of a familiar conundrum. “We weren’t getting any more ambulances, but the call volume was going way up,” said Michael Stringfellow, the EMS division chief at SAFD.

When he and others began digging into the department’s data, the inefficiencies were startling. Some of the city’s highest-volume utilizers were calling 911 for help more than 50 times a year. “And we were sending out either a patrol car, ladder truck, or engine truck, plus an ambulance, to every call,” Stringfellow told me. “Most of the time, we’d evaluate the patient and then have no other recourse but to take them to the hospital even if that wasn’t the right place for them. The hospital would evaluate them, then send them right back home, and the cycle just continued.” After talking to officials at 10 other EMS systems across the country that had had success with an MIH high-utilizer program, SAFD decided to launch its own six-month pilot program in 2014.

In a nutshell, the effort aimed to bend the call volume curve by targeting the system’s most frequent users. SAFD identified 343 people in San Antonio who had collectively accounted for 4,400 calls during the prior year. The department decided to target the top 50 most frequent callers and pulled those patients’ call and medical histories, then sent out Abbott and other MIH medics to knock on doors and learn why the patients called so much, and what other methods besides emergency transport might help.

“The biggest problem these people seemed to have was just a lack of knowledge of how to get the help they needed,” Stringfellow told me. “They didn’t know where else to turn, so they turned to 911.”

MIH medics worked to connect the patients to doctors, community aid programs, and other resources that could help, and followed up regularly to guide patients to the point where they were able to manage their conditions with this new network of support outside of 911. When the six-month pilot ended, the call volume of those original 50 high utilizers had been slashed by 78 percent. All told, SAFD estimated that the MIH pilot had saved its EMS medics about 1,000 runs to the ER. The program was so successful that in May 2016 SAFD officially made its MIH program permanent.

Today, if an SAFD EMS crew notices a patient who is habitually calling 911, it will refer the case to MIH, which will “pull up the patient’s medical history, hospital records, diagnoses, treatments, and make a game plan,” Abbott told me. After that process, it’s not always a sure thing that a patient will turn out to be a good candidate for the program, he said. “Sometimes the plans backfire. We’ll get a referral, but then when we check with the doctors, they might say that the patient is going to die on our watch—so if that patient calls, it’s a mandatory transport every time,’’ Abbott said. “Some people have had nine heart attacks or 10 strokes, and there’s really not much you can do” to reduce their 911 calls.

If a patient does seem to be a good fit for MIH, Abbott will take a ride out in his city vehicle to talk with them. Some people are less than receptive at first; others are cautious or even hostile. To break the ice, Abbott often tries to relate to them by talking about his own medical challenges, which include managing the care of his young daughter with cerebral palsy. “I find that it breaks down the walls—I’m just like, ‘You and I got the same problems, man. Let’s figure this out,’” Abbott said. “Then I just sit there yakking with them for an hour or so and try to come up with solutions. You talk a lot working on EMS, but in MIH we really talk a lot.”

“The problem a lot of times is just that the person has given up,” says Byron Green, another MIH medic. “We go in and say, ‘Hey, look, you can do this.’ We’re the pep squad for them. They see that someone cares about them, that someone will help them, go to the doctor with them, and make sure they have their medications. Sometimes they start feeling better about themselves and they’ll start to do a little better. We are really medics, case managers, social workers, and all of the above and in between.”

Like the pilot program, the results of these interventions have been phenomenal, Stringfellow said. The reduction rate in call volume for high utilizers continues to hover around 70 percent, saving SAFD’s busy ambulance units thousands of runs each year.

APPLICATIONS OF MIH

Building on the successes of the high-utilizer MIH program, SAFD has since expanded its efforts to include five additional programs under the MIH umbrella, all targeting specific populations such as opioid users and the homeless population. That path seems to be fairly typical for many EMS systems when it comes to MIH—they start with high utilizers, then eventually adopt a range of other MIH efforts to achieve further efficiencies and cost reductions.

“Many MIH programs tend to be in the areas that are kind of the low-hanging fruit, conditions that are the easiest to tackle and that tend to bring people back to the hospital rather frequently,” said Jeff Siegler, a physician and medical director of several EMS systems in greater St. Louis. “That includes congestive heart failure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, as well as our pediatric population and even mental health.”

At MedStar, the high-utilizer program is just the tip of the iceberg. In 2012, the organization created a “911 Nurse Triage Program” to take care of less-urgent 911 calls. Today, if a person in Fort Worth calls 911 with a low-acuity ailment, such as blisters, MedStar no longer even sends an ambulance; instead, a nurse in a car arrives to treat the patient in their home. That program alone has saved an estimated $6 million in transport and ER costs, in addition to the nearly $23 million that MedStar has saved over the years from its high-utilizer program.

While these internal programs can do a lot to move the needle for struggling EMS systems, perhaps the biggest growth potential—and the reason why health experts are so bullish on the future of the MIH model—are the potential partnerships with large insurers, hospital systems, and the federal government, all of whom seem ready to get on board. Increasingly, these outside health care payers and providers are seeing the successes of MIH programs and coming to EMS agencies with proposals in hopes of developing a plan to keep their patients healthier and out of the ER.

“We’re starting to see more insurance agencies like Blue Cross and Aetna realizing, ‘OK, we spent X number of dollars for ambulance transport and emergency department visits last year—but if we spend Y dollars to keep the patients healthier and out of the hospital, we potentially can save a lot of money and improve the health of those patients,” Siegler said. “As a result, hospital systems and insurance agencies, including the federal government, have now begun to come to EMS with a list of people who they’ve identified that could potentially benefit from mobile integrated health care. They’re asking EMS, ‘Can you go to those patients and try to enroll them in your program? And then we’ll fund your program to keep those patients healthier and out of the hospital.’”

For example, hospice agencies in Fort Worth are now paying MedStar to respond to all of their clients’ 911 calls, which MedStar treats much differently than a typical call. “When one of their clients calls for an ambulance, instead of taking them to the emergency room—which is often at the expense of the hospice agency and is not necessarily what the patient wanted anyway—we use our mobile integrated health care program to treat those patients in place,” Zavadsky said. “We notify the hospice agency so they can send the hospice nurse out to the residence while we’re still there so we can transition care back to the hospice nurse so that the patient’s wishes are met.”

With this growing array of new partners and options suddenly available, organizations like MedStar have had to revamp their systems and dispatch methods. Zavadsky told me that MedStar has preloaded its MIH-affiliated patients’ information—including IDs, names, addresses, dates of birth, and cell phone numbers—into its computerized dispatch system, so that whenever and wherever they dial 911 for help, the call is immediately flagged.

“Since it’s flagged, we know that the patient is in our high-utilizer program or he is in the Humana Medicare Advantage Program, so we add a community paramedic to that ambulance response,” Zavadsky explained. “We know that patient, we know what the patient’s vitals are under normal conditions, and we can tailor our response to that patient. We can do in-home dialysis, an EKG, an IV, and more. These paramedics, because they’re highly trained and can do additional point-of-care testing on scene, can make clinical decisions to determine if the patient really needs to be in the ER or not. Or, is it better for them to go to their doctor? Or, can we take care of them right at home?”

MedStar has similar arrangements with a home-health nursing organization, as well as at least one insurer. And, with the federal government’s ET3 model poised to take effect, which allows for nearly all low-acuity 911 calls to be treated like MIH, “we’re going to be doing this on a much larger scale with every ambulance,” Zavadsky said. “There’s no end in sight.”

Taken as a whole, MedStar and agencies like it “have really made the transition from a traditional EMS agency to something else,” Zavadsky said. “It took a long time, but I think we’re finally starting to get it. I’ve been in EMS for 40 years and I have never had as much fun in this profession as I’m having right now.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

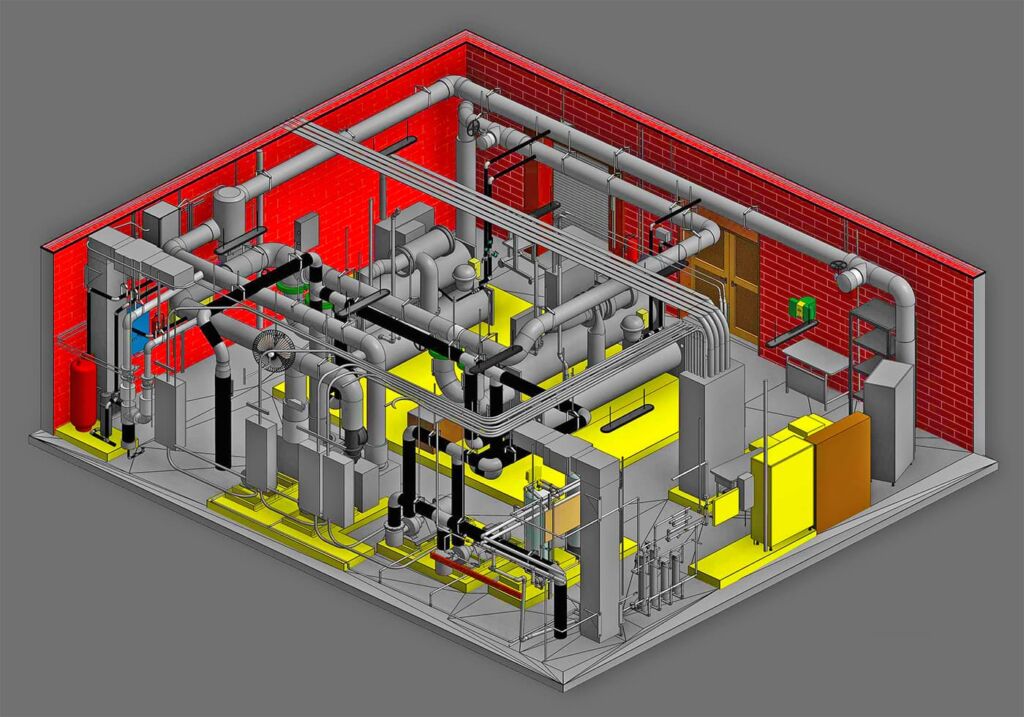

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.