Precision Fire Protection News

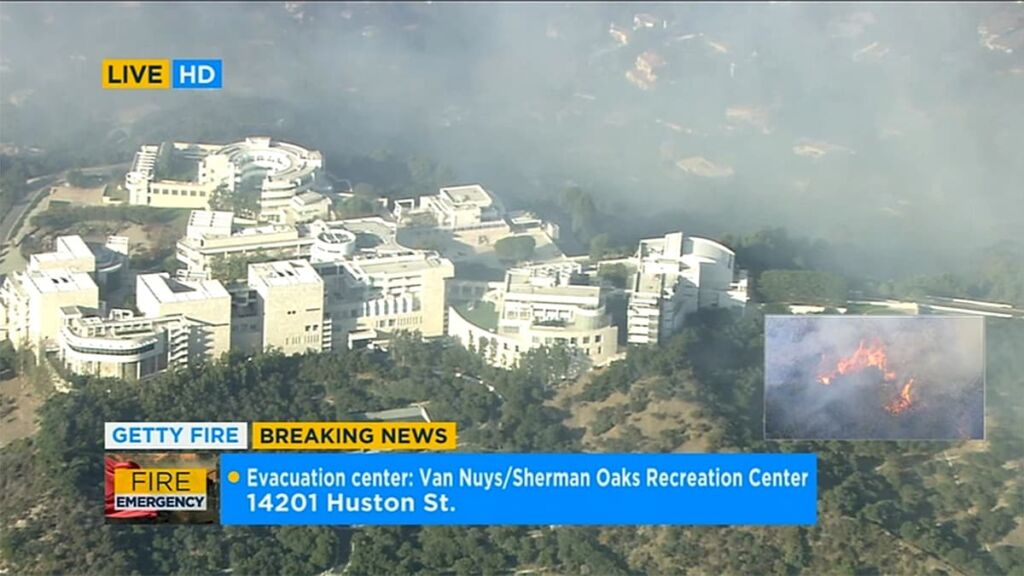

Outthinking Wildfires: A bold new plan from NFPA

A bold new plan from NFPA calls for ending the destruction of communities by wildfire in 30 years. Achieving that goal will require a coordinated effort among all levels of government and the cooperation of residents in fire-prone areas.

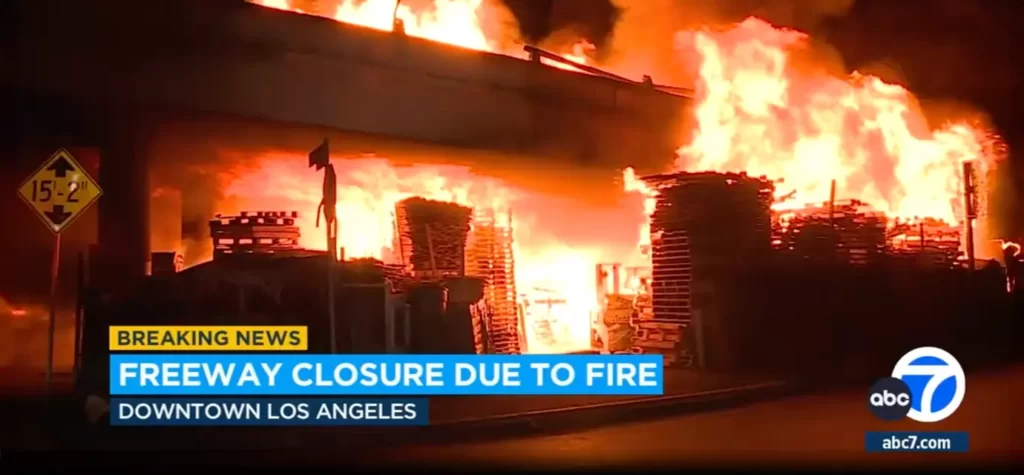

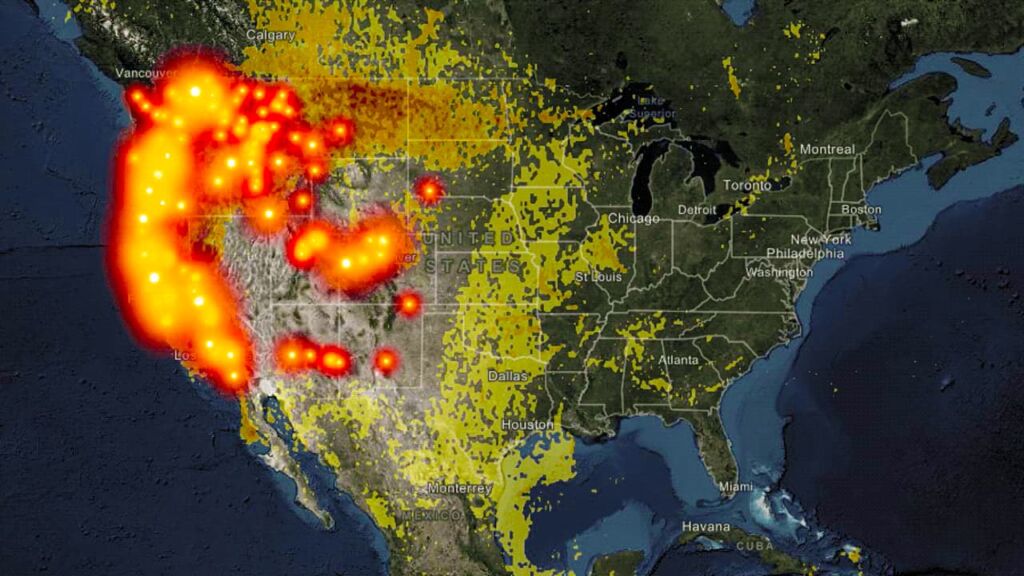

For more than half a century, Americans have been building their way into trouble with wildfires. Across the country, we insist on putting homes, businesses, and infrastructure into fire-prone areas, failing to understand or acknowledge the risks. An estimated 4.5 million homes nationwide face high or extreme risk of wildfire; in California alone, a million new homes are projected to be built in areas with very high wildfire risk in the next 30 years. Meanwhile, we grow accustomed to headlines proclaiming the latest “worst-ever” or “largest-ever” wildfire events and the unimaginable damage they inflict on landscapes, communities, and people.

It doesn’t have to be this way. This country has enough scientific know-how and experience with devastating loss to finally end this cycle of building and burning. It’s time to stop dodging the heart of the problem by bemoaning losses and pointing fingers. It’s time to take definitive steps toward creating a new approach to how we live with wildfire.

Outthink Wildfire, a new initiative launched by NFPA, is doing just that, with a single bold and attainable goal: to end the destruction of communities from wildfires in this country in the next 30 years.

As colleagues in NFPA’s Wildfire Division, we are excited by this ambitious new effort. Between the two of us, we’ve spent more than three decades on the front lines of the expanding crisis of community destruction due to wildfire, immersed in the details of disasters as we worked to create new and better solutions to the problem. And we’ve seen some amazing successes: neighborhoods saved because property owners took voluntary steps to reduce risk, local officials who used and enforced sound land-use and building standards, fire departments that safely and effectively responded to wildfires with proper training, equipment, and community cooperation. We’ve told these stories and celebrated these achievements as important parts of our work with NFPA.

But the success stories are far too rare because the traditional responses to wildfire risks aren’t enough. Solving the problem by relying solely on voluntary action and an informed public won’t work, either. Nor will placing the bulk of the responsibility on first responders. We can’t simply do what we’ve always done to address the problem; what is needed are new approaches, new tactics, and a new resolve to use what we’ve learned about the risks of the wildland/urban interface (WUI) over the past 50 years to create a new blueprint for addressing the nation’s wildfire crisis.

That’s where Outthink Wildfire comes in. The effort is based on five steps that must occur at all levels of government that will make it easier for communities to foster collaboration, enact change, achieve resilience, and protect themselves from wildfire. Those steps include:

- Helping the public understand its role in reducing wildfire risk and providing it with the tools to take meaningful action

- Requiring all homes and businesses in the WUI to be more resistant to ignition from wildfire embers and flames

- Ensuring that fire departments that serve WUI communities are prepared to respond safely and effectively to wildfire

- Working with all levels of government to increase resources for vegetative fuel management on public lands

- Ensuring that current codes and standards, as well as sound land-use practices, are in use and enforced for new development and rebuilding in wildfire-prone areas

Achieving these outcomes doesn’t mean a complete reinvention of the wheel. The core components of Outthink Wildfire are already being demonstrated in communities around the country as residents, local officials, developers, and fire departments experience expanding development, persistent drought conditions, and the effects of previous (and problematic) land-use policies, all of which contribute to an increased risk of wildfire. With the size and scope of the US wildfire challenge, reaching any one of the Outthink Wildfire goals will take time. But making progress toward all of them will save lives and property. The key to ending the long nightmare of the destruction of communities by wildfire is to start now.

—

Current codes and standards, as well as sound land-use practices, must be in use and enforced for new development and rebuilding in wildfire-prone areas.

Between 1990 and 2010, the number of acres in the US that exist in the WUI—areas where development encroaches on wildfire-prone landscapes—grew by 33 percent, to more than 190 million acres. The number of homes constructed on those lands expanded by 41 percent, to at least 43.4 million units. To better protect lives and property in the WUI, communities must address where and how they build homes and businesses, a process that will require the use of comprehensive land-use planning, including codes and standards.

Between 1990 and 2010, the number of acres in the US that exist in the WUI—areas where development encroaches on wildfire-prone landscapes—grew by 33 percent, to more than 190 million acres. The number of homes constructed on those lands expanded by 41 percent, to at least 43.4 million units. To better protect lives and property in the WUI, communities must address where and how they build homes and businesses, a process that will require the use of comprehensive land-use planning, including codes and standards.Land-use planning tools and practices offer the means to reduce the risk posed by wildfires to both future and existing development. Comprehensive, or general, plans guide the development of a community, usually in a timeframe of 20 to 30 years, and contain community goals as well as the policy objectives necessary to reach them. But the use of these tools and practices is not widespread. An extensive adoption of land-use planning at the local level, supported through state and federal policies, is urgently needed to lower the danger wildfires pose to thousands of communities.

This is not an easy process, as demonstrated by the community of Payson, Arizona. The town made news in 1990, when six firefighters died and 60 homes were destroyed in the Dude Fire. Despite that history, local officials have argued for years over the need to adopt basic wildfire safety standards for new construction. The debate took on new urgency following the deadly and destructive 2013 Yarnell Hill Fire in neighboring Yavapai County, which killed 19 wildland firefighters. In its aftermath, local media noted that neither Payson nor the county where it was located had adopted a building code that would require noncombustible roofs, a key factor in home and community survivability during a wildfire. Town council meetings in Payson routinely devolved into rancorous debates, fueled in part by resistance to what some saw as draconian measures that would hinder development and drive down property values. An ordinance was finally passed last year requiring vegetative fuel modification and maintenance around homes, but the town and county have yet to require that new homes be built safely.

States must require plan development that addresses a range of wildfire safety issues. Plans should include descriptions of the hazards and risks in the community, and they should identify policy objectives to reduce risk over time as well as the necessary actions to implement those policies. These policies need to incorporate building and zoning codes, such as those developed by NFPA, as well as other development requirements. They should provide assessments of the hazard that take into account the likelihood and potential intensity of a fire, as well as the risk that considers the impact of wildfire on community members and property—information that is available through a variety of sources including the USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Risk to Communities (wildfirerisk.org). These are the kinds of resources that are critical in helping planners and local leaders prioritize mitigation initiatives in their communities, track risk reduction activities, and incorporate critical wildfire safety measures into planning and regulatory policies.

Communities need this information at several levels, from regional to subdivision to individual parcels. These assessments can show where land management actions will be most effective for reducing risk, identify community members who are at the highest risk, and illustrate how individual properties might help spread wildfire. All of this information can help prioritize mitigation actions and guide development away from areas with the highest level of hazard. The more detailed information the community has developed through hazard and risk assessments, the better tailored these regulations can be. At the federal level, incentivization of planning for wildfires and hazard mitigation through access to funding and prioritization for land management activities must also continue.

—

All homes and businesses in the WUI must be required to be more resistant to ignition from wildfire embers and flames.

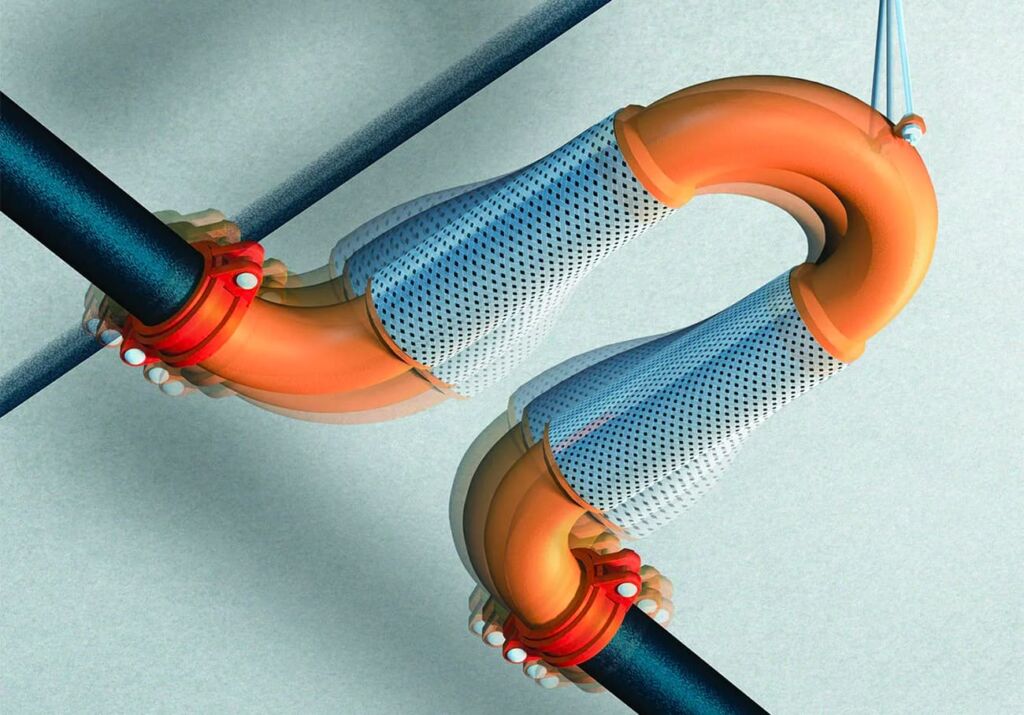

While influencing the siting and materials used in new construction are important steps in reducing the nation’s wildfire risk, much of that risk exists in structures that have already been built. To stem the tide of loss from wildfires, millions of homes and other structures must be retrofitted to reduce the risk of ignition, a transformation that can be realized through continued research and development, public education, financial incentives, and robust support from all levels of government.

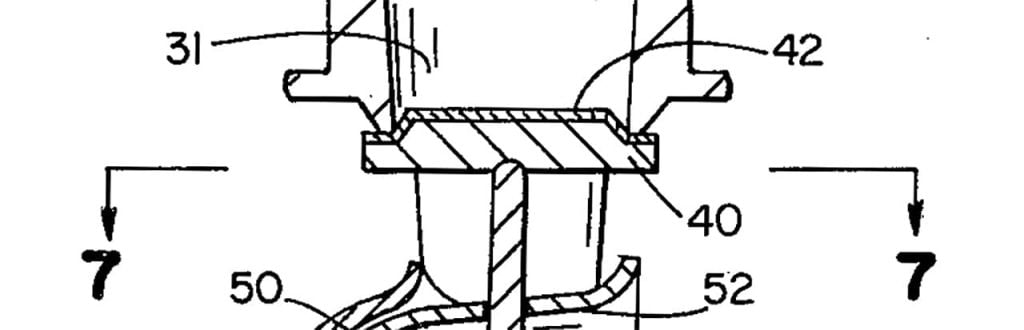

Research has consistently shown the role embers play in igniting structures in the WUI. It has also shown that there is an increased survival rate of homes constructed from fire-resistant materials on property that has been mitigated to remove sources of fuel for a fire. Continued research is needed in several areas, including the development of performance-based product test standards that better reflect how materials perform when exposed to exterior flame exposure, radiant heat, and the impact of embers from a wildfire. Developing these referenced standards will help guide architects, builders, and homeowners to easily source products and materials that will perform as intended during wildfires. Additional research is also needed to support the development and validation of retrofit methods, particularly those that are most cost effective.

Standards developers also have an important role to play. Building standards now exist to improve wildfire safety for new construction—including NFPA 1144, Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire, and Chapter 7A of the California Building Code—but there is no consensus standard for the retrofit of structures, particularly those within 30 feet of each other, and standards-making organizations need to fill this gap as soon as possible.

That’s because this kind of development is unfortunately common within the WUI, even in communities that have experienced devastating losses as a result of wildfire. In Santa Rosa, California, the city’s Coffey Park neighborhood lost more than 1,400 homes to the 2017 Tubbs Fire. But instead of incorporating the state’s ignition-resistance standards—some of the strongest in the world—in its efforts to rebuild the community, Santa Rosa stuck to its original risk mapping that characterized the neighborhood as “unburnable,” allowing developers to decide on their own designs and materials, many of which ignore wildfire ignition guidelines. City government was lauded for its relative speed in rebuilding Coffey Park, but all it has done is recreate a vulnerable community that exists inside the footprint of disaster.

States also play a significant role and can provide building owners and homeowners with the latest guidance on reducing the risk of structure ignition due to wildfire. States can do this through their own agencies and programs, and by supporting the development of a skilled workforce that can help owners assess and mitigate their homes and properties. States must have regulations in place requiring property owners to maintain defensible space, ensuring that the areas immediately around homes and other buildings are clear of vegetation and other sources of fuel.

States can also rely on voluntary initiatives such as Firewise USA® and the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, which have proven track records of transforming homes and communities. Residents of nearly 2,000 Firewise communities nationwide have already taken steps to make their homes more resistant to ignition from wildfire, from clearing yard debris to replacing combustible rooftops with materials that are fire resistant. Costlier, more intensive home improvements will require policymakers at the state and federal levels to consider creating tax credits or deductions to support retrofitting activities, and to ensure that grants and low-cost loans are available to aid mitigation and retrofitting efforts for residents of fire-prone areas who otherwise lack resources.

—

Most US fire departments are called upon to provide some form of wildland firefighting, but many of those departments have neither the training nor the equipment to fight those fires safely or effectively. Communities that rely on their fire departments to protect lives and property in wildfire events must identify municipal, state, and federal funding sources to help them properly train and equip their first responders.

According to NFPA’s Fourth Needs Assessment of the US Fire Service, 88 percent of US fire departments—roughly 23,000—provide wildland and/or WUI firefighting services. Of those, 63 percent have not formally trained all of their personnel involved in these activities. Personal protective equipment for wildland firefighting is available to all responders in just 32 percent of those departments, and firefighters in 26 percent of those departments have no wildland PPE at all. These gaps threaten firefighter health and safety and increase the risk faced by businesses and homeowners. Local fire departments report that brush, grass, and forest fire incidents account for nearly a quarter of the response calls they receive each year. From 2011 to 2015, wildfires resulted in an annual average of 1,330 fireground injuries to local fire department personnel.

Fire departments acknowledge their limited capacity. For example, 64 percent of US fire departments say they could manage structure protection for a maximum of two to five structures during a single wildfire incident; wildfires now routinely involve dozens or even hundreds of structures at a time. Similarly, 52 percent say they could manage responding to a wildfire of, at most, 10 acres; the average size of a wildfire in the US is nearly 170 acres. Meanwhile, many Americans continue to believe that the fire service will always have the capacity to respond to any fire or emergency event and mount successful rescues and saves. While state and federal agencies also perform wildland firefighting, the scope of those services differs significantly from that of local fire departments and generally does not extend to protecting homes, businesses, and other structures.

A case study prepared for the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center in 2010 illustrated that the reality of how firefighters are killed and injured during wildfires is often the result of insufficient training, no protective gear, and little or no direction. The study examined wildfires that occurred in Texas and Oklahoma in 2005 and 2006 and that killed four firefighters and severely injured seven. In interviews, firefighters who’d been injured in those fires insisted they would not change a thing about the operation, citing their training to protect life and property—even though they were fighting fires in grassy fields. The study’s recommendations emphasized training for rural fire departments, including teaching firefighters that no acre of vegetation (or any house, for that matter) is worth sustaining injury or risking death. It was clear from the study’s findings that minimal emphasis had been placed on such training.

In addition to prioritizing resources to train and equip their own responders for wildfire, communities whose local fire departments lack capacity to engage large fires must develop and maintain mutual aid agreements with neighboring communities to increase their response capabilities. At the same time, the public must understand that while the fire department’s response during a wildfire event is critical, it will be much less successful in an unprepared community. That’s why it is imperative that community members take action to prepare their own homes, businesses, and neighborhoods ahead of a wildfire event.

—

Government must increase resources for vegetative fuel management on public land.

For more than a century, the US government has invested heavily in a fire suppression infrastructure and workforce to ensure that most wildfires remain small and can be extinguished quickly. Effective response means that 97 percent of wildfires remain small and controllable, but it has also had an unintended and dangerous side effect.

Suppression disrupts the natural occurrence of lower-intensity wildfire, allowing vegetation and debris that would normally be cleaned out by periodic fires to accumulate. Denser, more continuous vegetative fuels create the conditions for severe wildfires that can overwhelm suppression efforts, conditions that science has demonstrated are exacerbated by climate change. To lower the risk of wildfire to communities, resources must be increased for fuel management on 120 million acres of federal land—and many more private acres—that are at high or very high risk of devastating fires.

Each year, about 3 million acres of public land are subjected to fuel treatments that include mechanical thinning and prescribed burning, a number that falls well short of the estimated 6.8 to 12 million acres per year experts believe is necessary to restore and maintain these lands. Between public and private holdings, the number of acres currently at risk for wildfire in the US is estimated to be as high as one billion.

In a 2019 report from the Government Accountability Office, the federal land management agencies acknowledged that insufficient staffing can hinder fuel management efforts, especially prescribed burns. According to a report from the National Association of Forest Service Retirees, the number of employees with the skills needed to support treatment and restoration work has fallen by 54 percent since 1992. The group concluded that without hiring more foresters, engineers, biologists, and project coordinator specialists, the US Forest Service would not be able to significantly increase its treatment and restoration activities. Conducting a strategic workforce review and creating plans to fill positions—particularly those that require years of training—is a crucial step toward increasing the capacity of the agency to support treatment and restoration work.

Despite these challenges, examples persist of effective land management in areas with high wildfire risk. On the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona, annual prescribed burns and mechanical treatments are conducted on more than 1,000 acres. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the San Carlos Apache Tribe use these methods to remove fast-growing grasses that could carry a wildfire into the community. The work also provides defensible space in which firefighters can work safely and effectively.

In neighboring New Mexico, Santa Fe National Forest officials have conducted fuels reduction over nearly 20 years, partnering with the state’s forestry division and Department of Game and Fish. A combination of mechanical treatments and prescribed burns covering 8,000 acres in the Jemez Mountains has helped reduce danger to the point that the intensity of the 2018 Venado Fire was dramatically reduced when it moved into the treated area. The fire slowed enough to allow firefighters time to contain it before it reached homes, and the lower-intensity fire resulted in less severe ecological damage.

Tackling the fuel treatment needs of US landscapes demands not only workforce investment, but also an increased funding commitment, cross-jurisdictional planning and cooperation, the honing of targeting and metrics, and additional assistance to meet landscape restoration needs and help communities prepare for and perform prescribed burns and other projects. Policymakers at the state and federal levels must create plans to allocate more funding for fuel treatment, or risk seeing the problem continue to grow. The US Forest Service needs to embrace a coordination role, directing funding and staff support work across jurisdictional boundaries. Further, land management agencies must pursue outcome-based metrics that track the progress made in wildfire risk reduction, including risk to communities, through the application of fuel treatments and other land management efforts.

—

The public must understand its role and take action in reducing wildfire risk.

Nearly 45 million homes currently exist in the wildland/urban interface (WUI) in the US, and more are built in fire-prone areas across the country every year. Even so, the majority of homeowners are poorly informed about wildfire risk and unprepared to take the steps necessary to minimize it, thereby jeopardizing lives, property, and the local fire departments that respond in wildfire emergencies.

It is critical that people take action to protect their homes and communities from wildfire, and that includes an understanding of the concept of the “home ignition zone.” Years of scientific research support the practice of removing fuel sources from the area immediately around homes, which reduces the risk of home ignition from embers or radiant heat during wildfire events. These include simple, low-cost steps such as clearing dead leaves, debris, and pine needles from roofs and gutters, keeping grasses mowed, clearing dry vegetation from the property, and removing stored flammable items from underneath decks and porches. Replacing combustible roof material and installing double-paned windows reduce risk even further.

Additionally, people who reside in fire-prone areas must understand the steps they may need to take in the event of wildfire, including evacuation. Residents should be urged to accurately understand their level of risk in these situations, create evacuation plans, and follow directions from the proper authorities. The 2016 Chimney Tops 2 Fire in Tennessee killed 14 people and injured more than 200; the National Institute of Standards and Technology conducted research on the factors that influenced people’s evacuation decisions during the event and found that only 5 percent of survey participants had previously experienced a wildfire evacuation. While less than a quarter of the respondents reported receiving an official evacuation warning, the majority of the 14,000 people who finally evacuated did so only after seeing or being impacted by flames, embers, and smoke, or when their homes or rental properties actually caught fire—situations that could easily have resulted in additional injuries and deaths. Funding social science research into how these warnings are delivered, received, and acted upon can help guide messaging and help prioritize programmatic strategies for convincing people to take the actions that will save lives and property.

In 2017 and again in 2018, large, rapidly spreading wildfires in Northern California resulted in shocking numbers of deaths: 42 in the 2017 fires, and 85 in the 2018 Camp Fire that destroyed the community of Paradise, where the average age of the people who died in the fire was 73. Most who perished in Paradise died in their homes or immediately outside them. These individuals, many of whom lived alone, may not have believed the warnings, if they received a warning at all, and were unable to self-

rescue. Paradise and other fire events have demonstrated that older and disabled populations are often overlooked in emergency planning, and that much more needs to be done to understand how these people receive and act on warnings.

While action at the individual level—including volunteer efforts such as NFPA’s Firewise USA®—is key for building community resilience and preparedness, leadership from all levels of government is essential in the effort to create a larger public that is more informed about wildfire and better prepared for a future with increased wildfire activity. To reach all 70,000 communities at risk from wildfire in the US, every state should increase its efforts to educate and advise property owners, and they should pursue partners to expand their reach and presence within communities.

—

The urgency is now.

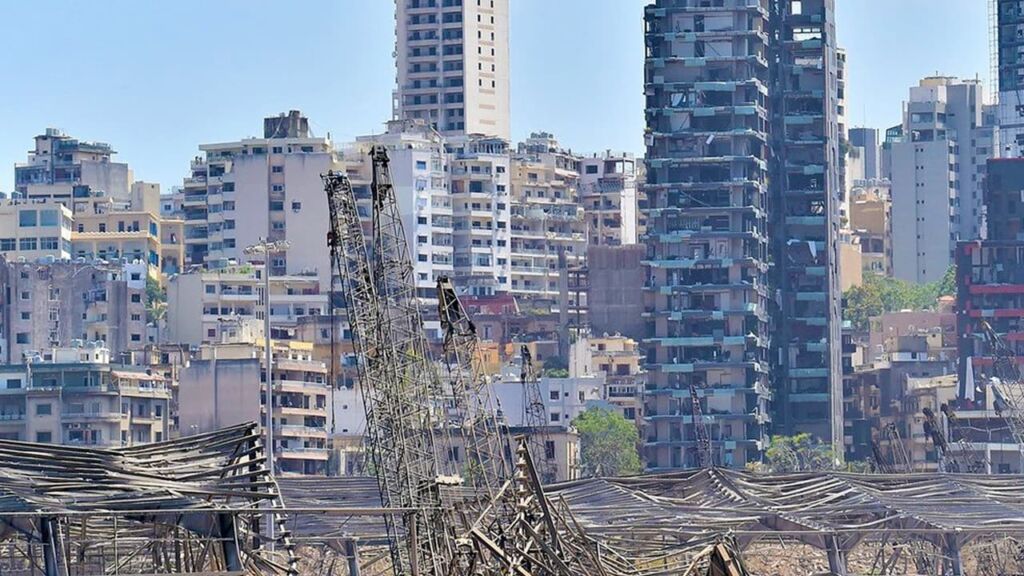

The long list of recent destructive wildfires is a stark reminder that the continued loss of life, property, and local economic vitality is unacceptable. Solutions are regularly suggested from every quarter, but to truly solve the wildfire problem will require a holistic approach—it is the only way we will be able to outthink wildfire.

NFPA’s ambitious call to eliminate the loss of communities from wildfire by 2050 is akin to the progressive response to urban conflagrations in the 19th and 20th centuries, a devastating problem that was addressed, and solved, through a determined, long-term, holistic approach. To address the challenge of wildfire, no stakeholder can wait until 2048. The residents at risk live in this challenge now. Our natural landscapes need proper management now. The resiliency of home construction and composition to most effectively face wildfire risks needs to be addressed now. Codes and standards designed to strengthen local resiliency must be in use and enforced now. We need to ensure that our local fire services are neither overburdened nor underprepared to meet the wildfire challenge now.

And your involvement must begin now. Visit the Outthink Wildfire online resources to learn what role you can play and how to begin creating a plan to achieve this goal in your community. Make the loss of communities to wildfire a lesson of history, not a part of our future.

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

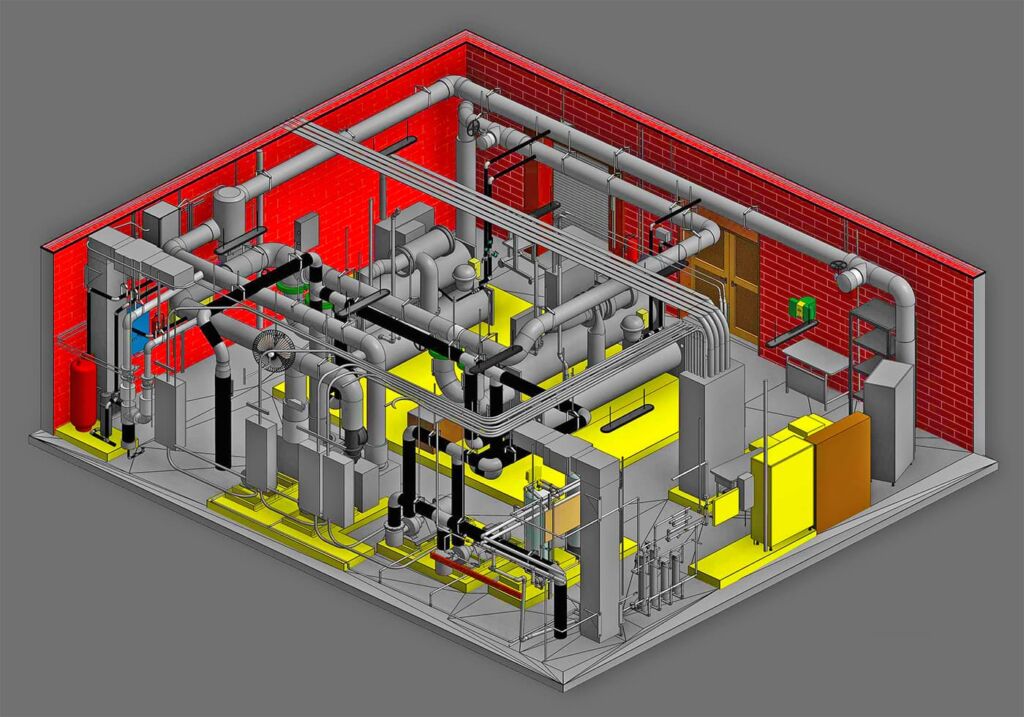

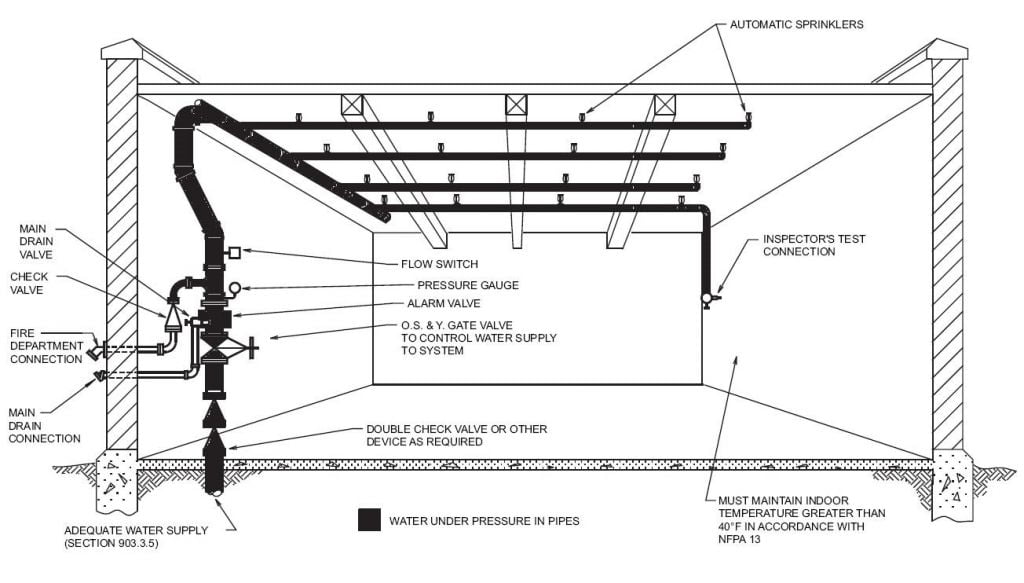

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.