Precision Fire Protection News

The Total Cost of Wildfire is Far Greater Than We Think

BY JESSE ROMAN, ANGELO VERZONI, and SCOTT SUTHERLAND

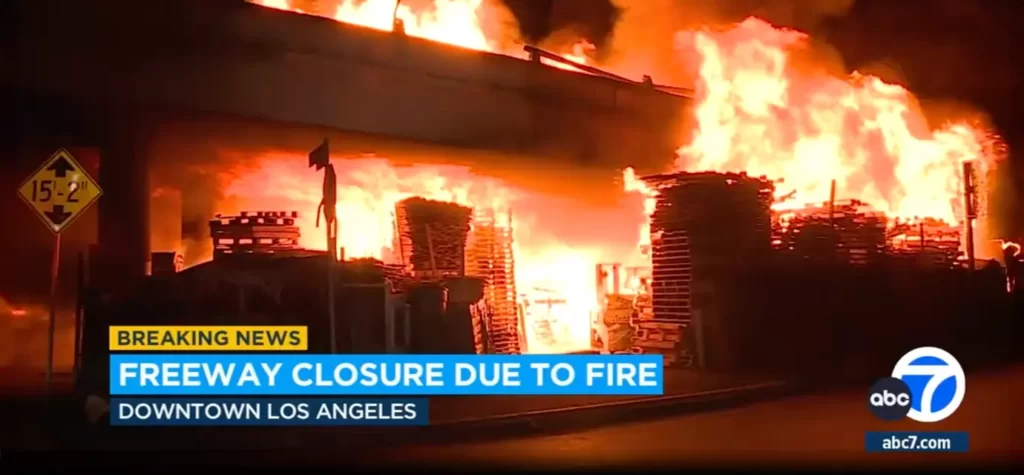

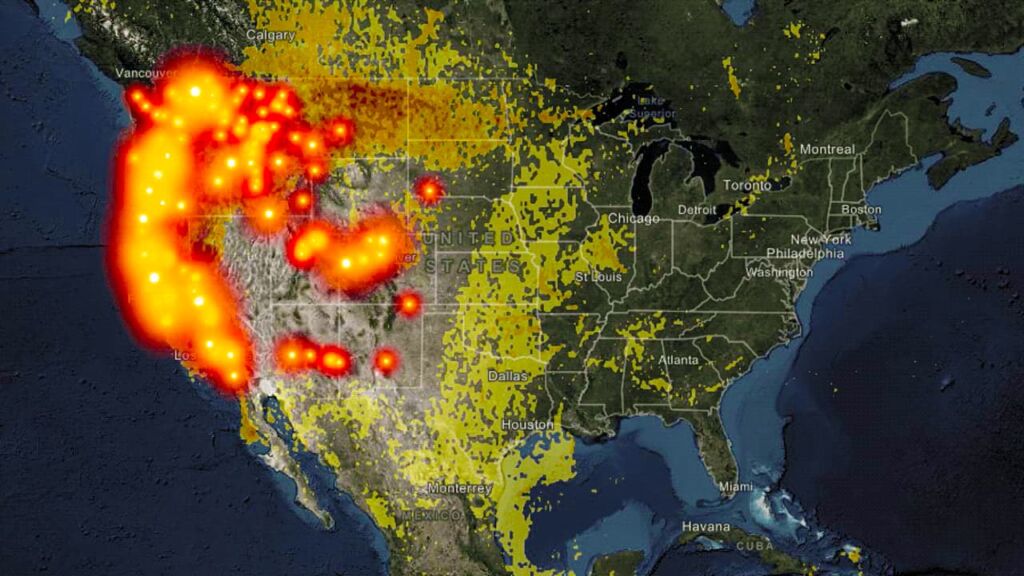

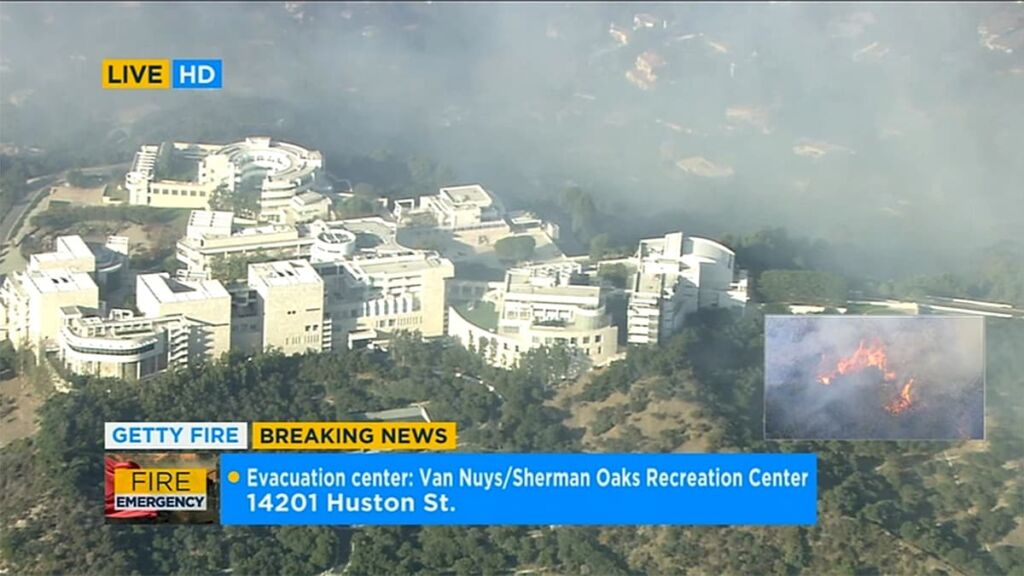

THE COST OF WILDFIRE is often measured in lives lost, buildings destroyed, and acres burned. In California alone, the 2020 wildfire season had, as of mid-October, killed more than 30 people, destroyed some 8,500 structures, and torched a record-breaking 4 million acres of land—double the acreage burned in 2018, the state’s second-worst wildfire season on record.

But the total cost of wildfire extends well beyond these three metrics, starting with the money it takes to contain or suppress the fires—a figure that has grown significantly over the past three decades. There are also less quantifiable metrics that may be even more costly: disruptions to business, taxes, and tourism; residents left with soaring medical bills; and polluted air, soil, and waterways.

Federal wildfire suppression costs in the United States have spiked from an annual average of about $425 million from 1985 to 1999 to $1.6 billion from 2000 to 2019, according to data from the National Interagency Fire Center. State suppression costs have also risen; in California, the average annual suppression cost has nearly doubled over the past decade compared to the previous one, reaching about $400 million. The most recent CAL FIRE data available suggests the agency was on pace to spend nearly $700 million on suppression for the 2019/2020 fiscal year. “All this money spent on suppression means less money for prevention efforts, which is key to addressing the problem of wildfire losses,” says Michele Steinberg, director of the Wildfire Division at NFPA.

Less understood are wildfire’s indirect costs, which, according to experts interviewed by the New York Times in September, likely outweigh the more apparent, direct costs associated with property loss and suppression. A report published in 2018 by Headwaters Economics, a nonprofit research organization, estimated that for the 2017 wildfire season in California, insurance claims for property loss plus suppression costs only accounted for about $14 billion out of the staggering $100 billion estimate of the season’s overall cost. Indirect costs associated with environmental cleanup, lost business and tax revenue, and property and infrastructure repairs accounted for the $86 billion difference, the report says. The popular weather forecasting service AccuWeather has predicted that costs for the 2020 wildfire season could total between $130 and $150 billion.

Wildfires leave behind toxic debris in the air, soil, and waterways, requiring billion-dollar cleanups in some cases, and they can also have a long-lasting, costly impact on human health. A study published last year in the journal GeoHealth reported that the 2012 wildfire season in Washington led to $2.3 billion in health care costs, most related to respiratory illnesses including asthma and pneumonia. A 2017 study led by the Environmental Protection Agency estimated that the cost of short-term exposures to US wildfires occurring between 2008 and 2012 that led to premature deaths or hospital admissions at $63 billion; the cost of long-term exposures was estimated at $450 billion. Scientists fear the 2020 wildfire season—which at times has turned cities like Portland, Oregon, into the world’s most polluted—could leave thousands of people sick and facing sizable medical bills. “In the short term, we have the potential for emergency-room-type events, but in the longer term, we have the development of more chronic disease,” a professor of preventative medicine told Vox in September.

The world’s wildfire crisis is the result of a complex variety of factors.

BY NEARLY EVERY METRIC, wildfires are occurring around the world with more frequency, in more places, and are larger and more destructive on average than at any time in our recorded history. Arguments are sometimes made that attribute the problem almost exclusively to one factor or another—ineffective or harmful wildfire and land management policies, unchecked development in fire-prone areas, increased temperatures and prolonged periods of drought—but the reality is that untenable wildfire conditions worldwide have reached crisis proportions.

Much of the recent attention has been on the historic wildfire season underway in California, with discussions seeking to explain, or in some cases assign blame for, the state’s handling of wildfire in its forests. While the scale, associated damage, and expense of California’s fires make them impossible to ignore, experts point out that the focus on “forests” misses the larger concerns of the wildfire crisis affecting the entire nation. NFPA defines wildfire as fires occurring in brush, grass, and forest lands, meaning that the forested foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada are just one type of ecosystem impacted by wildfire. The larger actuality is that wildfire is a natural phenomenon that affects every corner of the country, from the wiregrass expanses of Florida to the New Jersey pine barrens to the rangelands of Texas. According to a 2018 NFPA report, of the estimated 306,000 brush, grass, and forest fires in the US that local fire departments responded to annually from 2011 to 2015, 77 percent involved brush, grass, or some combination of the two. An estimated 10 percent involved forests or woods.

The more accurate term here is “fire management,” which places the emphasis on the hazard rather than a specific habitat—and also implies a cohesive strategy. But cohesion can be difficult to maintain with wildfire events that can span vast amounts of land administered by an array of local, state, and federal agencies. Priorities do not always align, and resources are frequently stretched. Pushing resources toward suppression efforts as fires rage leaves fewer resources to pursue land management measures such as forest thinning and other critical mitigation work.

Closely related to management and mitigation is development, especially in the wildland/urban interface, or WUI. NFPA defines the WUI not as a physical space, but rather as a set of conditions that can pose a threat to the built environment in the event of a fire. Communities across the country have demonstrated a willingness to build in areas they know to be fire-prone, even after catastrophic fires have leveled thousands of homes and other structures. Solutions exist, including stricter regulations on what can be built where; requirements to build with fire-resistive materials; and strategies for communities, counties, and states to purchase buffer lands that cannot be developed and can help protect property against wildfire, to name a few. The question is whether policymakers can summon the will to enact such steps.

Warming temperatures are also a factor in our wildfire crisis. Scientific data have indicated that even a modest rise in average temperature can dramatically reduce the amount of moisture in the landscape, especially over prolonged periods, creating ideal conditions for fires to ignite, spread rapidly, and burn with more ferocity. The 2019–2020 fire season in Australia was an alarming precursor to the US season; record temperatures and drought periods in some affected areas contributed to vast wildfires that burned as many as 46 million acres, by some estimates—more than five times the likely acres burned this year in the US. In California, the hottest August on record corresponded with the most acres burned on record: more than 4 million, or nearly half the acres burned by wildfire nationwide.

| Warmest years on record | California’s top years for acres burned (since 1987) |

| 2020 | 2020 |

| 2016 | 2018 |

| 2019 | 2008 |

| 2015 | 2017 |

| 2017 | 2007 |

| Source: NOAA | Source: CALFIRE |

While debates abound about why there is a crisis, more and more communities are burning. If fire-prone regions want to stem this tide, there needs to be new approaches to wildfire. The present situation cries out for moving beyond arguing about causes and taking action to reduce loss.

FOR MOST OF HUMAN HISTORY, wildfire has been a local problem with mostly local consequences. But over the last decade, a new reality has emerged: wildfires aren’t just displacing local communities, they are affecting life on our entire planet.

“In this new era we are in—this era of megafires and growing fire seasons, this era of climate change—no one of us can succeed alone,” then-US Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell said in a speech at the 2009 World Wildfire Congress in Argentina. “In the century to come, success in managing wildfire will depend on building partnerships on a global scale.”

That idea is even truer today. In just the last few years, historically severe fires have besieged nations around the world, including the United States, Canada, Australia, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Chile, Russia, and Brazil—even regions like Greenland and Northern Europe, where wildfires have traditionally been tame. Many of these events have required international cooperation to battle the blazes, offer aid to affected citizens, and provide resources and expertise for recovery.

During the historic 2020 Australian bushfires, where 47 million acres burned, firefighters from the US, New Zealand, Canada, and Singapore pitched in; the tiny Pacific island nation of Vanuatu pledged about $250,000 to assist victims, and even Papua New Guinea declared it had 1,000 soldiers and firefighters ready for deployment. People across the world sent donations, and many knitted blankets and protective pouches to help the estimated billions of animals who lost their homes. International researchers pledged their expertise in helping curtail the unfolding ecological disaster any way they could.

As the world continues to get hotter and dryer, most experts believe that wildfires will become even more intense in areas like Australia, California, and the Mediterranean. A recent state-sponsored inquiry into the recent Australian fires concluded that “it is clear that we should expect fire seasons like 2019–20, or potentially worse, to happen again.” Due to accelerating climate change, similarly dire conclusions have been reached by scientists in Europe and North America. Recent unprecedented fires above the Arctic Circle could exacerbate concerns even further; wildfires have burned vast swaths of typically frozen, carbon-rich peat soils, releasing a record 244 megatons of carbon into the atmosphere—more than Spain releases from burning fossil fuels in an entire year, according to Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), an agency of the European Union.

As the wildfire crisis grows, so have international efforts to fight it. Ongoing projects include research to better understand wildfire and to train a new generation of global experts; efforts by the United Nations to develop strategies to enhance cooperation between nations and improve fire management practices; and international grants, such as the $22 million pledge last year by the G7 countries to fight fires in the Amazon rainforest.

Whether these and similar efforts are enough to address the crisis depend on our willingness to recognize the threat and to act with urgency.

— Jesse Roman

Stricter land use and development policies are essential.

THE HANLY FIRE of 1964 and the Tubbs Fire in 2017 ignited almost exactly 53 years and 10 miles apart in the small wine-country town of Calistoga, California. The fires both grew rapidly and travelled a remarkably similar path over the parched hills on their march southwest toward Santa Rosa.

How the fires are remembered, however, couldn’t be more different. In 1964, the Hanly Fire burned 84 homes and 24 summer cabins, prompting The Press Democrat newspaper to declare on its September 22, 1964, front page: “Miracle of Santa Rosa: No Deaths, Damage Low.” The Tubbs Fire, meanwhile, was catastrophic, destroying about 5,600 structures and resulting in 22 deaths. At the time, it was the most destructive wildfire in the state’s history.

The differences are clear. Where the Hanly Fire met a thinly settled agrarian region, the Tubbs Fire encountered thriving suburbs of hundreds of thousands of people, many living in densely settled neighborhoods. All it took was an ember to light one house, and wind-driven fire could quickly spread to many more.

The transformation of northern California from a wild, fire-adapted region to one of sprawling suburbs susceptible to wildfire is a familiar story across the United States. In the 1990s alone, “some Western and Southern census tracts tripled in population in a decade,” said Michele Steinberg, director of the Wildfire Division at NFPA. “Building had to keep up. And where there is development investment, there is a strong impetus and desire for fire suppression.”

Not only does more development provide increased opportunity for fire to destroy, it forces governments to protect it by extinguishing every fire. That’s a major problem in regions like the American West, which needs to burn to maintain a healthy ecosystem. Instead of burning naturally, underbrush and other fuels build up over decades, eventually leading to fires that grow too fast and burn too ferociously to be contained.

| 33 Percent |

| Estimated percentage of all US homes located in the wildland/urban interface, or WUI |

| 4.5 million |

| Number of US homes located in teh WUI that face high or extreme wildfire risk |

| 2 million |

| Number of those high or extreme risk homes located in California |

| 1 million |

| Number of new homes projected to be built in “very high” risk wildfire areas in California by 2050. |

While there are no easy solutions, experts say that improved land-use policies, coupled with smarter development, would go a long way toward minimizing future devastation in the built environment. Those steps include limiting or even eliminating development in high-risk wildfire areas and requiring fire-resistant materials and landscapes where development is allowed. But in too many places, that simply isn’t happening. “In California, every impediment [to smarter land use] comes back to money and competing priorities…it really comes down to what local governments, economically speaking, are incentivized to do,” Edith Hannigan, the statewide manager of the California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection’s land use planning policies, said in an interview with NFPA Journal. The problem is apparent even in Santa Rosa, where city officials have drawn criticism for mostly disregarding the state’s suggested wildfire-smart building standards in order to replace thousands of burned structures as quickly as possible.

The longer we go without widespread adoption of stricter land use and development polices, the more difficult it will be to ever get a handle on the problem. By 2050, an additional 12 million acres of wild and agricultural lands in California will be turned into exurban land—defined as housing settlements outside of the suburbs—according to a 2014 study published in the journal Land Use Policy. Over that time, the study reported, an estimated 1 million new houses will be built in areas in California that are designated as very high risk for wildfire.

The pace of growth is similar across the western and southern US. According to the US Census Bureau, western communities with populations under 5,000 people—areas that are typically prone to wildfire—averaged 13 percent population growth over the last decade, the highest for small towns in any region. By contrast, the northeast saw its small-town population decline by 3 percent over the same period.

IN A RECENT INTERVIEW with the Washington Post, Char Miller, a professor of environmental analysis at Pomona College in California who has written widely on wildfire in the United States, was asked who’s responsible for managing the country’s wildfires. “Everybody is,” he replied.

With no single entity in charge, any one of a number of agencies can take control of a fire, depending on who the land belongs to. “And that shifts, fire to fire—it’s a very complicated system,” Miller said. Stakeholders range from communities and counties to states, the US Forest Service, and the federal Bureau of Land Management—and, of course, private landowners. Perspectives can vary, priorities don’t always align, and resources are a constant issue. “You can see the dilemmas and the dimensions of this problem, which is not easy to fix and not easy to fully understand,” Miller said. “It complicates fire management on the one hand and, when the fires are gone, [land] management on the other.”

While the Forest Service has demonstrated its skill at building coalitions among these actors, Miller added, “fire cuts through those kinds of relationships and exposes the flaws.”

The historic 2020 California wildfires exposed an array of divisions. As the state wrestled with a series of massive and intense wildfires—including five of the six largest wildfires in its history—the Trump Administration blamed the size and severity of the blazes on California’s “forest management” practices. State officials, including Gov. Gavin Newsom, countered that the problem was more complex than that and was being driven by forces that included climate change. Experts, meanwhile, pointed out that much of the land impacted by the state’s largest fires was actually under federal management.

Malcolm North, a forest ecologist at the University of California, Davis, has urged a more comprehensive approach to defining the problem. “One camp is saying it’s all climate change driven, and the other is saying it’s all forest management,” North told the New York Times. “The reality is that it’s both. I get kind of frustrated at this all-or-nothing type of approach.”

Regardless how the debate is framed, some kind of new, radical, big-picture reassessment of our response to wildfire is critically necessary, since the consensus among many experts is that our current approach isn’t working and hasn’t worked for the last century. This may mean a more streamlined agency alignment for land management, fire suppression, and emergency services. It almost certainly means a large and deliberate step away from our continued focus on fire suppression in the name of protecting property, and a fierce and rapid embrace of a new kind of fire management.

It will also mean adopting a resolute willingness to say no to new development in fire-prone areas. A 2018 study prepared for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimated that about one in three homes in the US are now located in the wildland/urban interface, or WUI. Miller has placed the number at about 34 million households, while the analytics firm Verisk estimated last year that 4.5 million of the homes located in the WUI faced high or extreme risk of wildfire. Two million of those were in California.

Despite ongoing catastrophes—including the near-total destruction of Paradise, California, in the 2018 Camp Fire—communities around the country insist on developing areas that are historically prone to wildfire. “Zoning commissions and planning boards have got to stop building subdivisions in landscapes they know from the get-go are high-severity fire zones,” Miller said. “If we could get them to do that, we’d have the most effective mitigation strategy, which is not to put people in the way.”

Even then, though, any new relationship we create with wildfire will need to accept that we’re playing catch-up; it’s less about waging war with an implacable foe than it is learning to live with an elemental force. “Whatever kind of management we do,” Miller said, “know that it’s only going to be partially successful.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

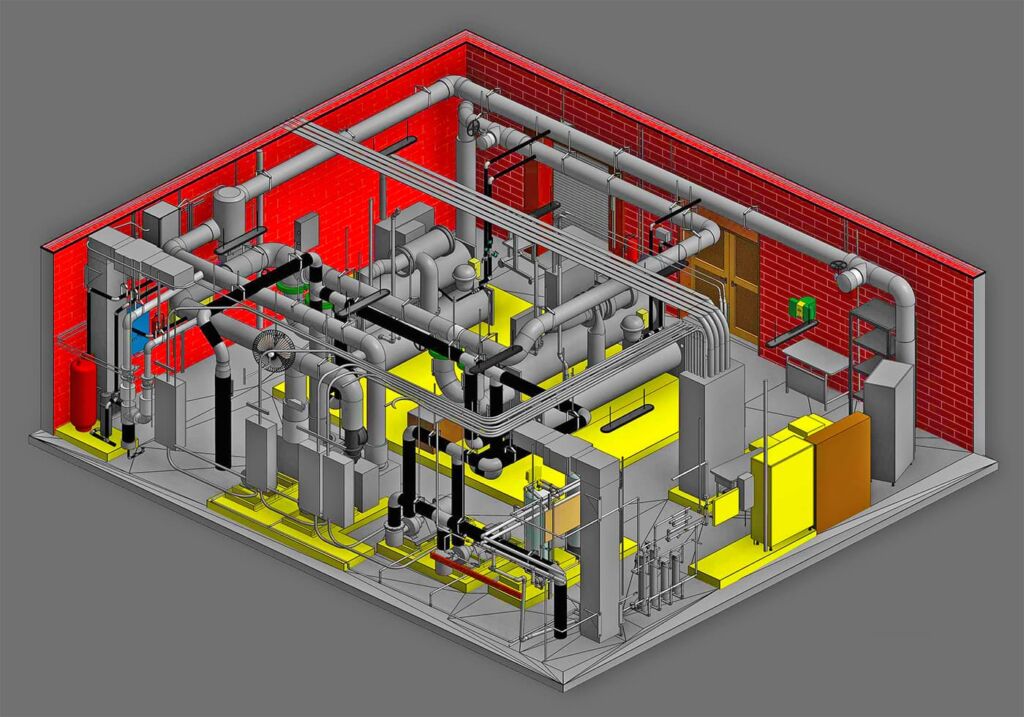

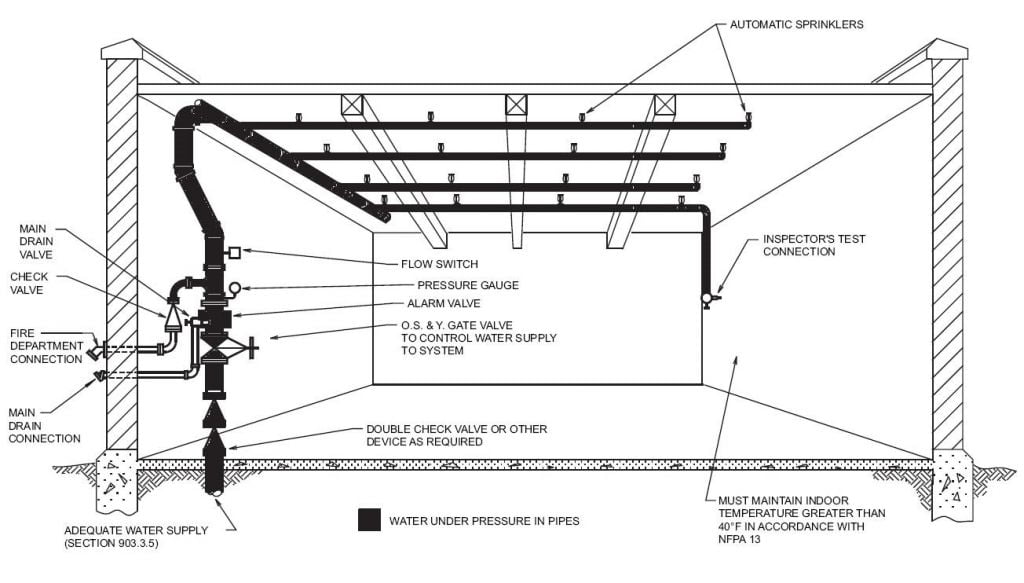

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.