Precision Fire Protection News

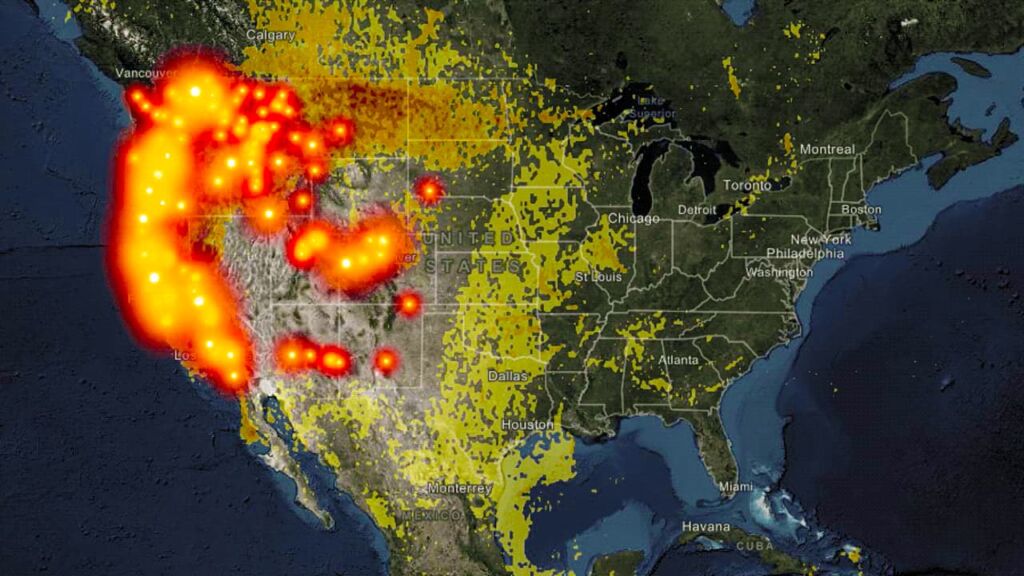

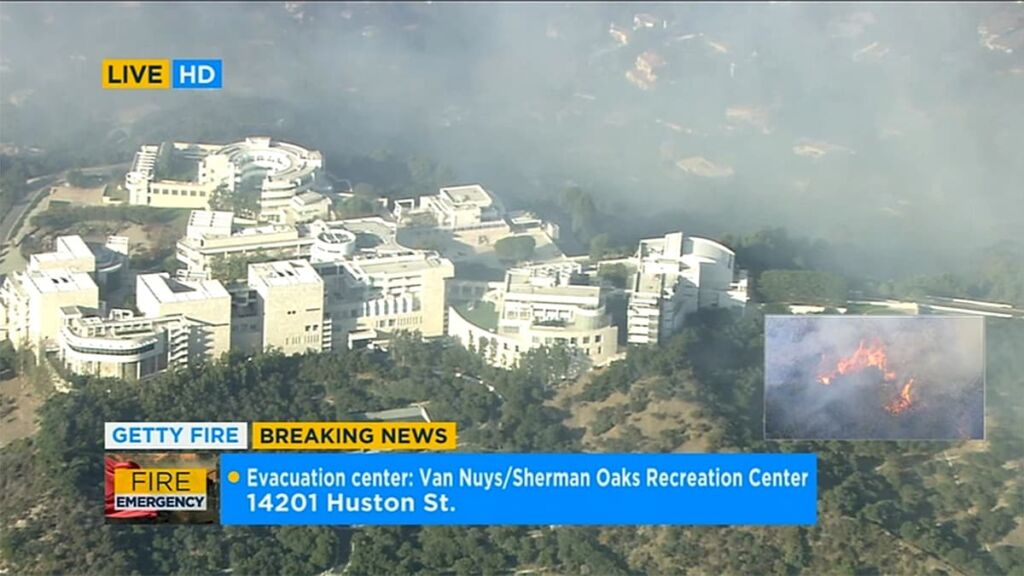

The Kilauea Calamity

Months of volcanic eruptions on Hawaii’s big island challenge emergency management officials and raise questions about how to prepare for such events

Paradise turned into “a little bit of hell” is how Ellen Gannet described the situation on Hawaii’s Big Island to The New York Times in May. The house where she had raised five children was encased by hardened black lava after the island’s most active volcano, Kilauea, began erupting earlier in the month.

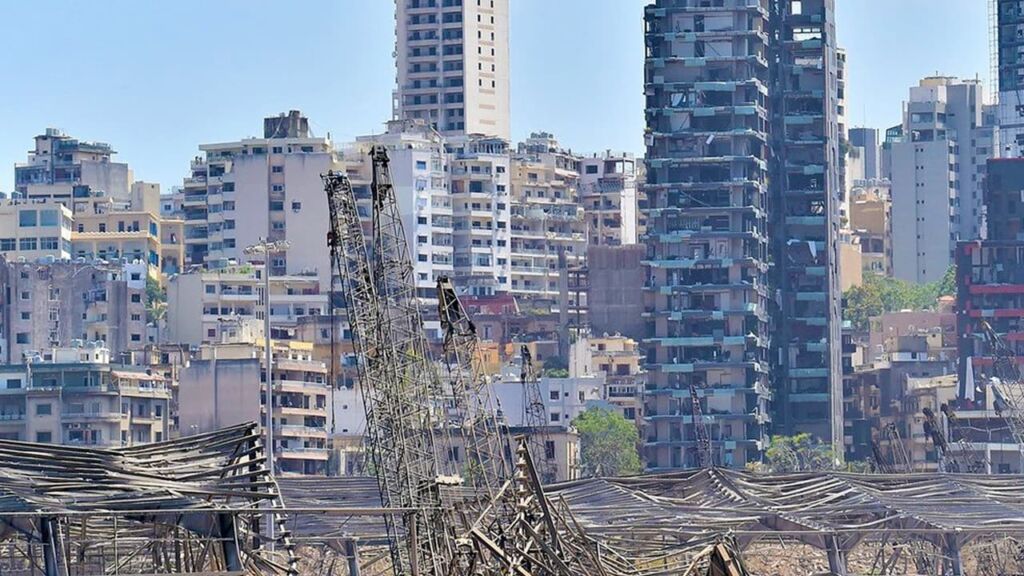

The eruptions have led to thousands of evacuations and various ongoing public safety concerns. Lava flows have leveled homes, swallowed cars, swept away roads, and destroyed or threatened critical infrastructure. As of late June, there was no sign of the eruptions abating.

As the situation nears its third month, Hawaii’s experience has raised questions about what, if anything, can be done to help emergency officials respond to and prepare for when the earth spews its molten core onto civilizations above. It also raises the question of whether NFPA codes and standards could play a larger role in addressing the threat of natural disasters for certain facilities like power plants—the same question that was raised after a string of powerful hurricanes pummeled the United States late last year, crippling the petrochemical infrastructure of the Gulf Coast.

So far, human casualties have been low. There has only been one known injury; a man’s leg was reportedly shattered from his shin to his foot after it was hit by lava spatter. (A Hawaii government spokesperson told Reuters that lava spatter “can weigh as much as a refrigerator and even small pieces of spatter can kill.”) But thousands of people have faced warnings of noxious gases like sulfur dioxide wafting miles through the air from volcanic vents. There have also been reports of blue flames rising from the cracks of roadways and hardened lava, the result of burning methane gas that formed underneath plants crushed by the lava flow.

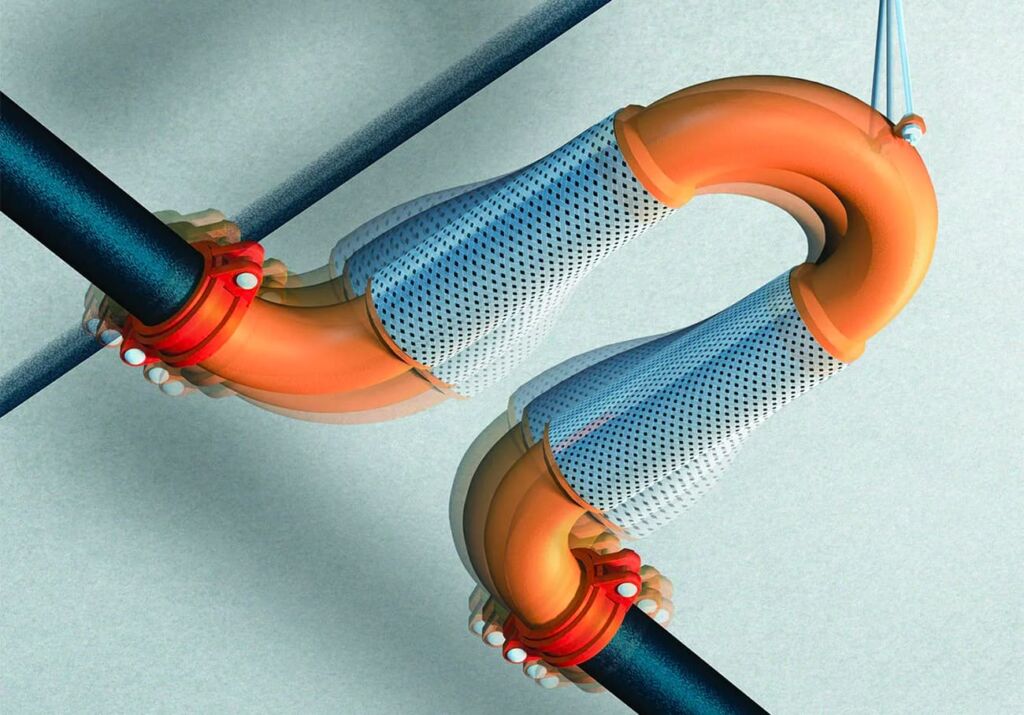

Perhaps the most alarming scenario amid Kilauea’s chaos, however, played out on the fourth week in May when a wall of lava began encroaching on the Puna Geothermal Venture (PGV), a power plant servicing a large percentage of the Island of Hawaii. In the path of the lava flow were the plant’s 11 geothermal wells, which harvest heat and steam from far beneath the earth to drive electricity-generating turbines. Plant workers and emergency management officials had to act swiftly and creatively to cap the wells to prevent lava from destroying them. A breach of the geothermal wells, which run as deep as a mile and a half into the ground, could have caused deadly gases to waft out.

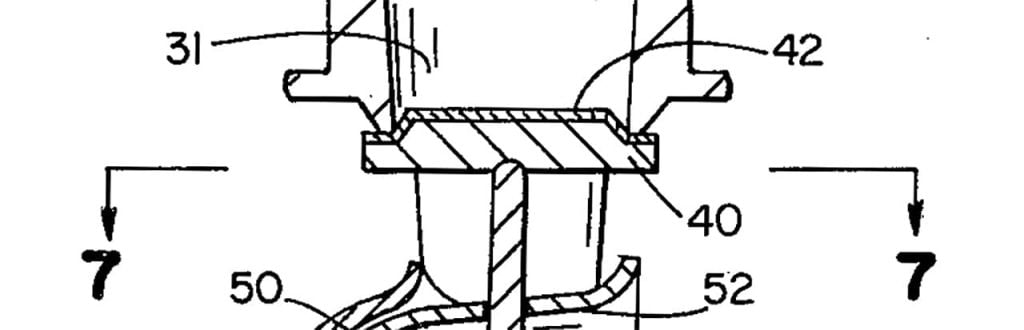

“There’s a steam release, there’s many chemicals, but primarily the critical factor would be hydrogen sulfide, a very deadly gas,” Thomas Travis, Hawaii’s Emergency Management Agency administrator, told reporters as he spoke about the consequences of such an incident. To keep that from happening, Travis and other emergency management officials worked around the clock to come up with a plan for PGV workers to execute. They decided that workers would shut off the wells with metal pressure valves, fill the wells with cold water, and then cap the wells with metal and other materials.

But there was no way of knowing for sure it would work, and not everything went according to plan. One of the wells, for example, was so hot that as workers poured cold water into it the water evaporated instead of filling the well. They then tried saltwater to no avail, before having to use mud. Additionally, while the metal pressure valves had been tested to withstand 3,000 to 5,000 pounds per square inch, they hadn’t been tested to withstand that pressure with the added element of lava. “If you put tremendous heat on any metal, it changes how much pressure and stress that metal can hold, [so] that’s why having lava flow across the well causes some uncertainties,” Travis said. “I have researched this and … I have found no case in which lava has overrun a well that has been shut down like these have been.” As of June, two of the PGV wells had been overtaken by lava but have so far been deemed stable.

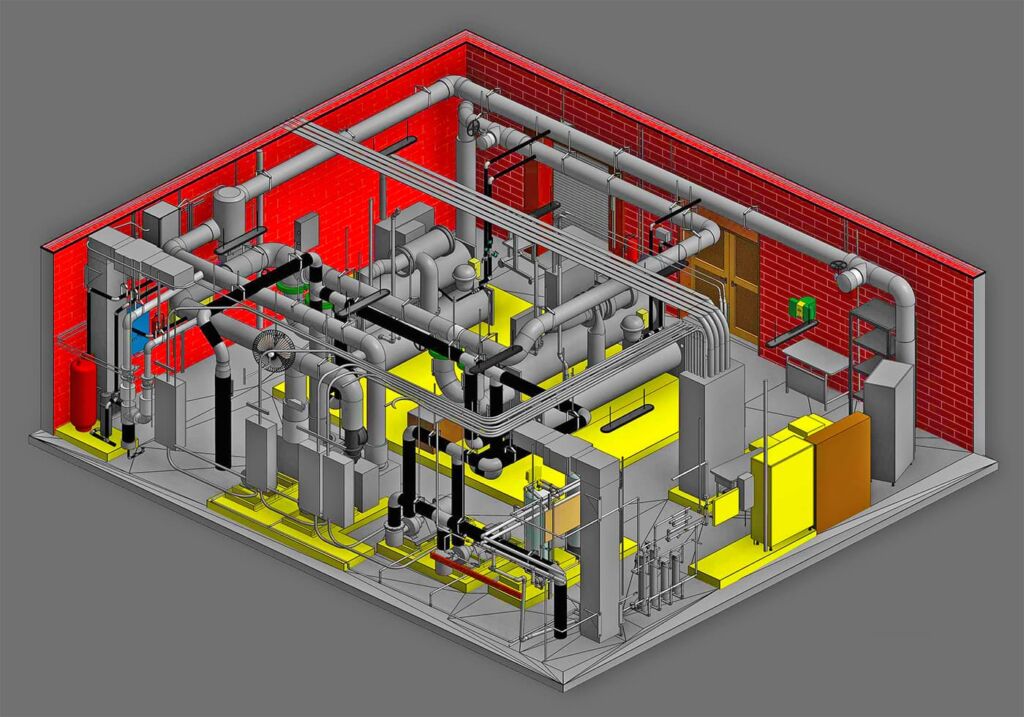

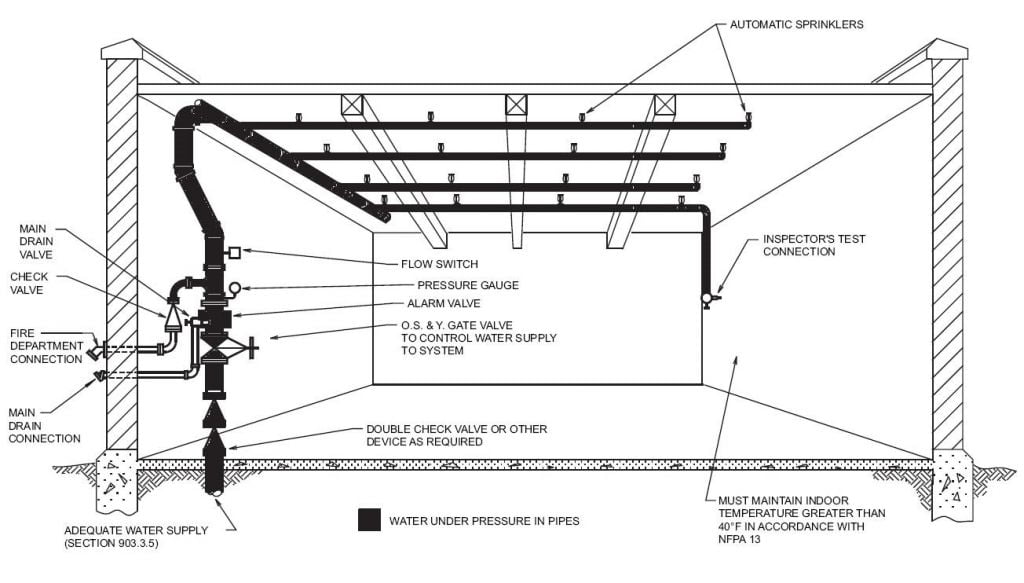

Although NFPA 850, Recommended Practice for Fire Protection for Electric Generating Plants and High Voltage Direct Current Converter Stations, includes a chapter on geothermal power plants, it doesn’t give recommendations on how to protect a plant from lava flow, according to Brian O’Connor, the NFPA staff liaison for NFPA 850. Rather, it recommends a fire risk evaluation be done to address special hazards including volcanic activity and other natural disasters. Similarly, NFPA 1600, Disaster/Emergency Management and Business Continuity/Continuity of Operations Programs, requires that organizations evaluate hazards associated with volcanic activity and other natural disasters when conducting a risk assessment, which can be applied to geothermal power plants.

“Both NFPA 1600 and 850 ask the user to be prepared for hazards they anticipate,” O’Connor said. “This is fairly broad but should include volcanic activity if, for example, you have a power plant near an active volcano.”

At least one part of NFPA 1600, which advises facility managers to have vendors available to provide parts on relatively short notice, was displayed by Hawaii emergency management officials and PGV staff. They had to quickly retrieve the parts to cap the wells from offsite—the final step in securing them—and they were able to do so before the lava got too close, Travis said.

Still, the incident, much like last year’s hurricane season, raised the question of whether documents like NFPA 850 should go the extra step in providing recommendations specific to certain natural disasters. “The incident in Hawaii resonated in the same way for me as Hurricane Harvey,” said Guy Colonna, NFPA’s division director of Technical Services, referring to the hurricane that battered the Houston region last summer. After Harvey reportedly caused hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil to spill out of industrial facilities along the Texas coast, Colonna and other experts told NFPA Journal that they thought codes like NFPA 400, Hazardous Materials Code, should be more specific about addressing the threat of extreme weather to the petrochemical industry. (The chair of the NFPA 400 technical committee said the issue will appear on a future meeting agenda. Read more in the November/December 2017 feature article “Storm Season.“)

Perhaps when it comes to an event as rare and uniquely challenging as a volcanic eruption, though, even the best efforts are futile. “I don’t think there’s much you can do with something as destructive and unpredictable as lava,” O’Connor said. Scientists echoed that sentiment in interviews with the media about the Kilauea eruptions. “Everyone in the volcanology community is just heartbroken. But from a scientific perspective, we know there’s just no way to divert this lava flow,” a NASA researcher told USA Today. The same article pointed to past unsuccessful efforts to stop lava flow with water, walls, and even bombs.

For many native Hawaiians, lava’s unstoppable force can be explained by something other than science. They took the disaster in stride, believing, like their ancestors, that the eruptions are the work of Madame Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes and fire, and that nothing can be done about them. “Our deity is coming down to play,” a hula dancer and poet told The New York Times. “There’s nothing to do when Pele makes up her mind but accept her will.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

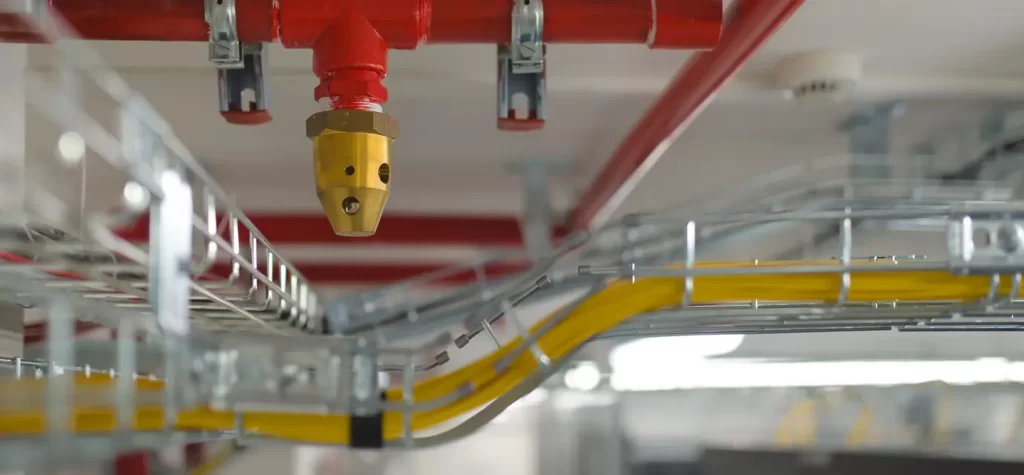

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.