Precision Fire Protection News

Large-Loss Fires and Explosions in the United States

Large-Loss Fires and Explosions in the United States

An incident at a Texas chemical facility accounted for more than half of the dollar losses associated with large-loss fires last year—a category that saw a significant reduction compared to 2018

BY STEPHEN BADGER

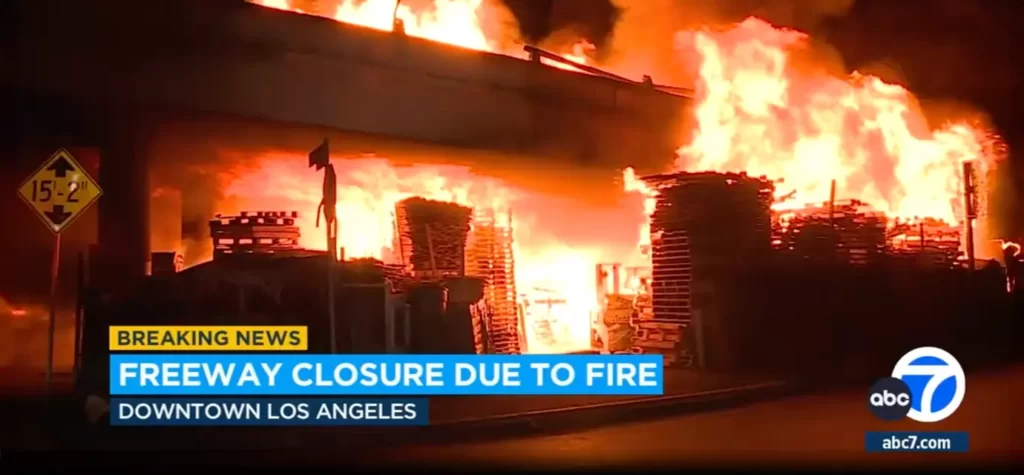

Shortly after 1 a.m. on November 27, 2019, a powerful explosion occurred at a petrochemical plant in Port Neches, Texas. Firefighters on duty at a nearby fire station were awakened by the blast and walked to the rear of the station to see what had happened. They found the rear door blown in and saw a large fire with heavy smoke in progress at the nearby plant. They attempted to notify dispatch but found that their computers and radio traffic had been disrupted. A portable radio was used to notify dispatch of the explosion and fire. All of the department’s units, as well as mutual aid companies, were asked to respond.

When the first firefighters arrived at the plant’s main gate, workers indicated that all personnel had been accounted for. It was not known if there were injured workers at that time. A command post was established with the local fire chief, mutual aid chiefs, and plant officials. At that time, the authorities determined that a half-mile radius around the plant needed to be evacuated. Local and mutual aid firefighters and police officers handled the evacuation.

RELATED: Read a list of selected large-loss incidents from 2019

According to media reports, the blast was felt up to 30 miles (48 kilometers) away. Thirty people were working in the plant at the time, and several injured employees were treated and sent to local hospitals. A second major explosion occurred about 13 hours after the first, and several smaller explosions occurred throughout the day. The fire continued to burn over the next several days and involved the chemical 1,3-Butadiene, which is used in the production of rubber and is a health hazard. Local evacuations took place in the following days, and a curfew was enacted.

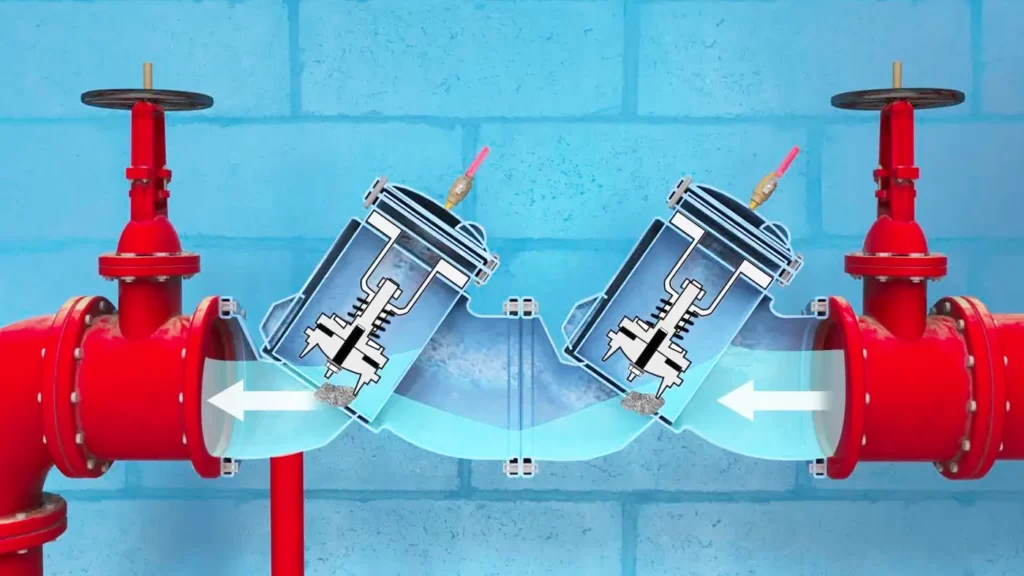

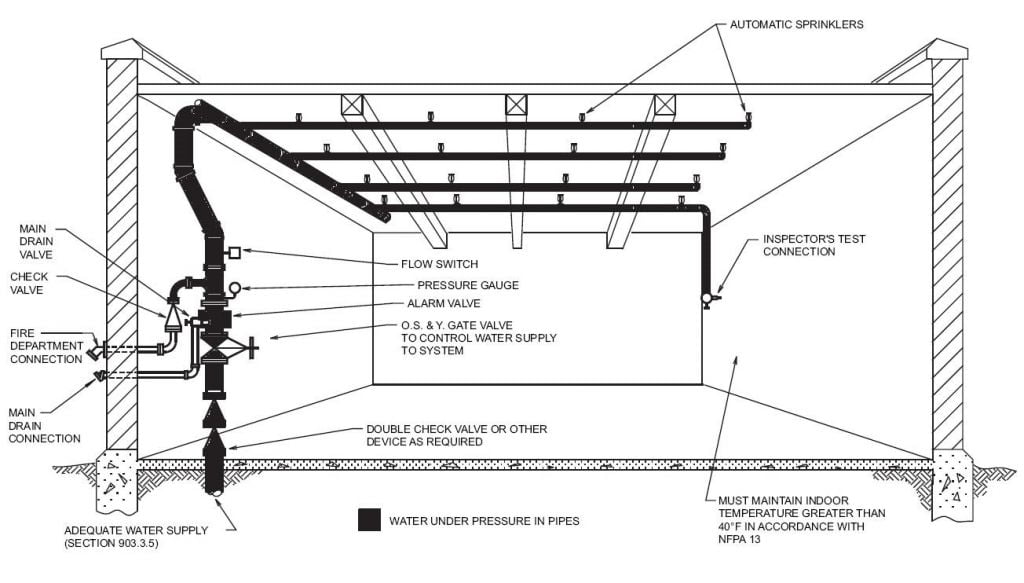

A large portion of the plant’s process and storage areas was damaged, as was much of the infrastructure for those areas. A number of properties throughout the surrounding community were also damaged. The plant was one story in height and had a floor area of 840,000 square feet (78,039 square meters). The plant had a wet-pipe sprinkler system, but it did not operate, the reason for which was not reported. The explosion occurred when a spark or ember ignited flammable/combustible liquids in the processing area, though what caused the spark was undetermined. The blast knocked out the power to the plant. There was no report as to the number of liquid storage spheres or tanks on the property.

The estimated damage caused by the explosions and fire was $1.1 billion, making it the largest dollar loss fire or explosion in the United States in 2019.

NFPA reports annually on large-loss fires and explosions that occurred in the U.S. in the previous year. These fires are defined as events that result in property damage of at least $10 million. In 2019, there were 26 such fires and explosions, resulting in an estimated $1.9 billion in direct property damage and losses.

In order to compare losses over the past 10 years, we adjust losses for inflation to 2010 dollars. When adjusted for inflation, the number of fires in 2019 that would have been categorized as large-loss fires—that is, fires resulting in a loss of $10 million or more in 2010 dollars—drops to 19 fires, with an adjusted loss of slightly more than $1.8 billion.

In 2019, 10 fires, two fewer than the previous year, resulted in more than $20 million each in property damage. These fires resulted in a combined property loss of $1.7 billion, or 89.3 percent of the total loss in large-loss fires in 2019.

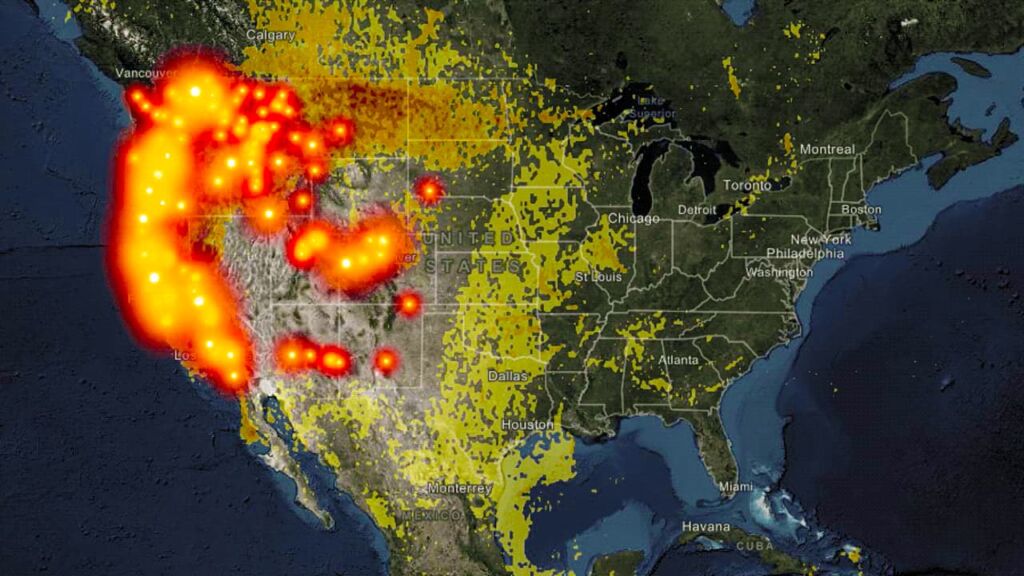

The Texas petrochemical explosion and fire was the ninth-largest loss incident in the nation’s history, according to NFPA records. In terms of property losses, this incident is surpassed only by the 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center and seven wildfire conflagrations in California that occurred between 2003 and 2018.

Compared to the past 10 years, the 26 incidents in 2019 is tied with three other years for the second-highest number of large-loss fires or explosions, the highest being 2018 with 37 incidents. Over the past 10 years, 25 fires have occurred that each resulted in a loss of more than $100 million, with two of them in 2019. Of these largest-loss fire events, 17 were wildland/urban interface (WUI) fires, seven were structure fires, and one involved a U.S. Navy submarine. These fires resulted in combined losses of over $34.9 billion.

According to the summary of the 2019 U.S. fire loss report, published in the September/October issue of NFPA Journal, U.S. fire departments responded to an estimated 1,291,500 fires last year, which resulted in an estimated loss of $14.8 billion. Many of these fires were small or resulted in little or no reported property damage. Although the 27 large-loss fires accounted for 0.002 percent of the estimated number of fires in 2019, they accounted for 12.7 percent of the total estimated dollar loss. In human terms, these 27 fires accounted for five deaths and at least 60 injuries.

In 2019, there were 11 fewer large-loss fires than in 2018, with a decrease of more than $11 billion in losses. The difference was due to major wildfires in 2018 that accounted for losses of $12.3 billion. In 2019, there were 22 fewer large-loss structure fires than in 2018, but the property loss associated with those fires was $783 million higher than the year before, due in part to the Texas incident. The number of non-structure fire incidents was the same in 2019 as in 2018, but the losses associated with those fires last year was $11 billion less.

Where the fires occurred and how

In the second quarter of 2020, when much of the data gathering for this study occurred, the U.S., along with the rest of the world, was hit with the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding that fire departments had their hands full with emergencies, we did not make additional follow-up requests and phone calls to fire departments. As a result, less detailed information was available for the 2019 large-loss study.

Of the 26 large-loss fires in 2019, 18 involved structures and resulted in a total property loss of $1.4 billion, or 73 percent of the combined losses for all large-loss fires. The non-structural fires included four wildland/urban interface fires and four vehicle fires that resulted in combined losses of $511 million, or almost 27 percent of the losses in all the large-loss fires.

Of the 18 structure fires, five occurred in manufacturing properties, four in industrial properties, three in restaurants (one was vacant), three in warehouses, one in an office property, one in a hotel under construction, and one on an oil and gas field.

The combined loss for the five fires in manufacturing properties was $1.2 billion. The manufacturing properties included petrochemicals, adhesives, casket manufacturing, metal refining, and vehicle parts assembly.

The four industrial properties included two power generation plants, one electric substation, and a fruit processing facility. Their combined losses totaled $66.3 million.

The three warehouse fires had a combined total loss of $35.1 million.

A restaurant explosion and a coffee shop explosion caused a combined loss of $56 million. In addition, a fire in a vacant restaurant resulted in a loss of $10 million.

The office property fire resulted in a loss of $14 million and the fire in the hotel under construction resulted in a $15.5 million loss. The oil and gas field fire was a $16 million loss.

Four fires occurred in wildland properties, with a combined loss of $432.2 million, and four involved vehicles, with a combined loss of $79.3 million.

For 11 of the 26 large-loss fires last year, the cause of the fire was undetermined, unknown, or was not reported. In several cases, the destruction was so extensive that investigators could not determine a definitive cause or could not rule out several possibilities. Other fires are still under investigation or their causes have not yet been reported.

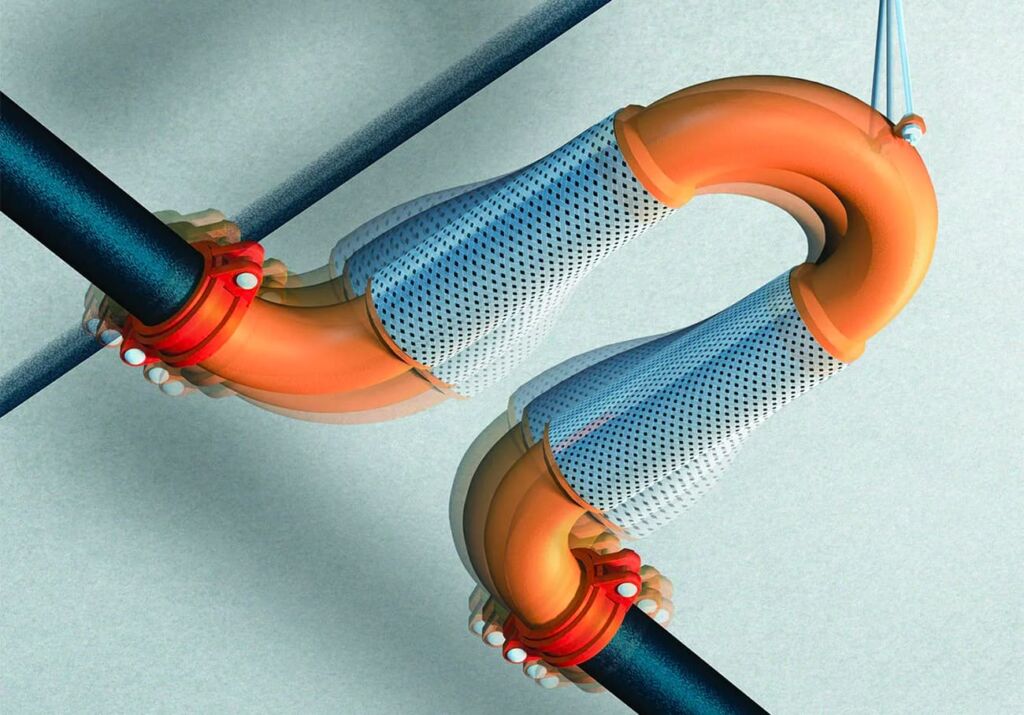

A cause was reported for 10 of the 18 structure fires. Five of the reported causes involved part failures or leaks, while other causes included an unspecified short circuit, an unreported type of electrical failure, supplies stored too close to a furnace that was in use, a lightning strike to flammable/combustible liquids at an oil field, and a gas meter turned on in a vacant restaurant (though it was not reported if it had been turned on deliberately or accidentally). Of the causes involving part failures or leaks, two were leaks from natural gas mains with undetermined ignition sources, including one that resulted when workers damaged a pipe, and one that was the result of a pipeline fracture. The exact cause of the other three failures/leaks was not determined.

The cause was reported for two of the four vehicle fires. One was due to an unknown type of electrical failure in a control box and one was attributed to an unknown mechanical failure when a wheel rubbed against a vehicle body part.

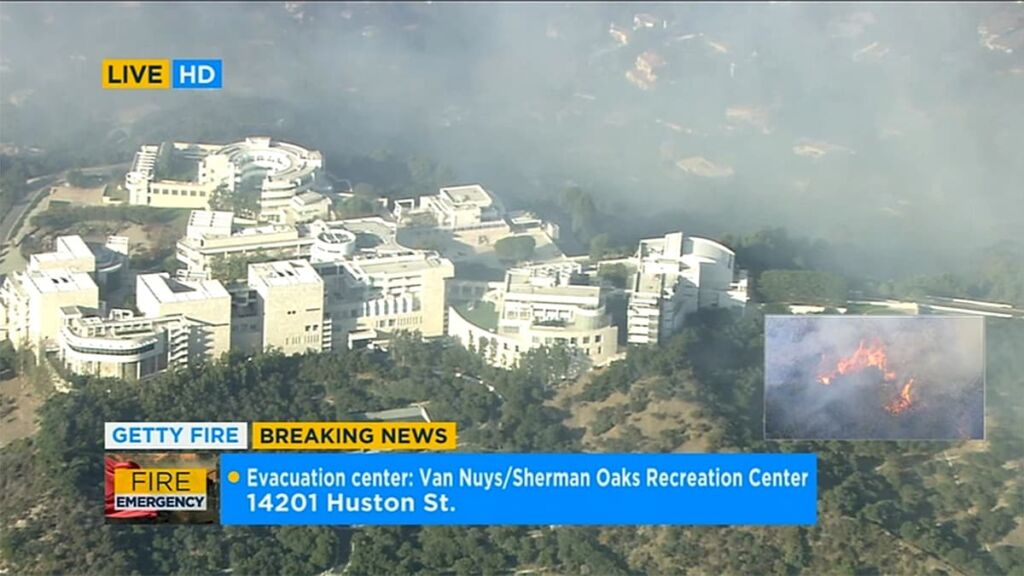

The cause was reported for three of the four wildland fires. One occurred when a truck dumped a load of smoldering debris next to dry vegetation, one when an electrical wire malfunctioned and sent sparks into dry brush, and one when a tree limb landed on high-tension wires that sent sparks into dry grass and brush.

The operating status was reported for 15 of the 18 structure fires; in 12 incidents, the facility was open, operating, or had workers on site. Three were closed and the properties were unoccupied.

Six of the 18 structure fires broke out between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m. and had a total direct property loss of $1.2 billion. One of the non-structure fires broke out between 11 p.m. and 7 a.m. and had a total direct property loss of $12 million.

Smoke detection and automatic suppression equipment

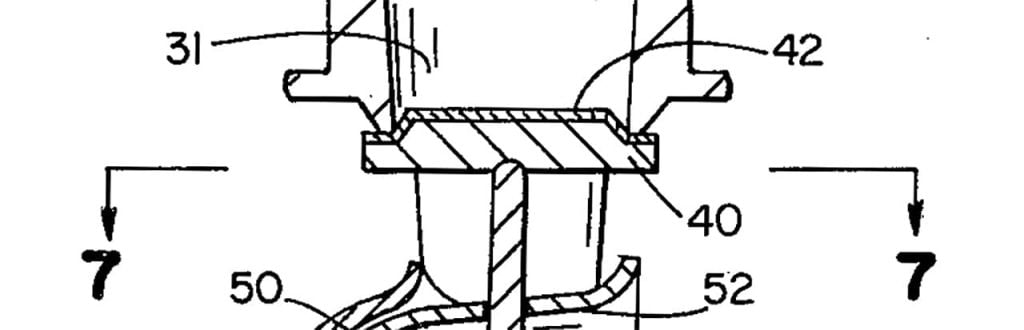

Information about automatic fire or smoke detection equipment was reported for 10 of the 23 large-loss structure and vehicle fires. Of those 10 fires, four properties had detection equipment present; one of the four systems operated as designed, and in three cases the operation was unreported. The six remaining properties had no automatic detection equipment installed.

Information on automatic suppression equipment was reported for 11 of the 22 structure and vehicle fires. Of those 11, seven properties had suppression systems and four did not. It was not reported if any of them operated. In three cases, the systems did not operate: one because the sprinkler systems were installed but not yet activated due to construction, one because the system was manual and was turned on, and one because it was damaged by an explosion.

Complete information on the presence of both detection and suppression equipment was reported for 10 of the 22 structure and vehicle fires. Four had neither system present, four had both detection and suppression equipment, and two had just suppression equipment.

What we can learn, where we get our data, and acknowledgments

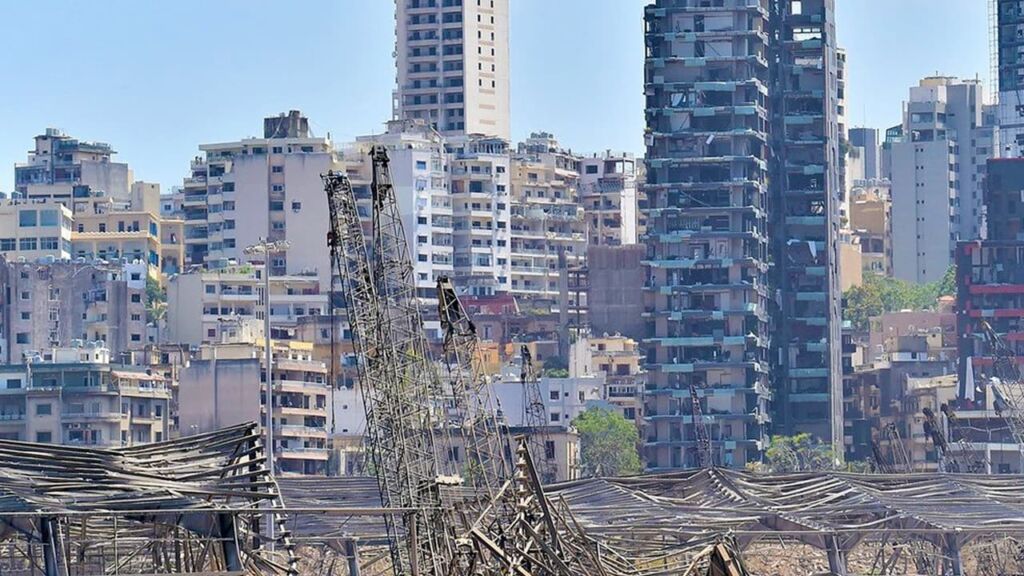

Adhering to the fire protection principles reflected in NFPA codes and standards is essential if we want to reduce the occurrence of large-loss fires and explosions in the U.S. Proper construction, proper use of equipment, and proper procedures for chemical processes, storage, and housekeeping can help make fires and explosions less likely to occur and help limit fire spread if one occurs.

When fires do occur, proper design, maintenance, and operation of fire protection systems and features can keep those fires from becoming large-loss fires. In the case of large-loss wildfires, we should encourage new building and rebuilding to follow the NFPA wildfire safety standards, and for at-risk neighborhoods to work together using the guidance provided in the NFPA Firewise USA® recognition program. These standards and guides can help reduce the risk of wildfire to structures and their surroundings, and can help limit fire spread and the resulting destruction.

NFPA identifies potential large-loss incidents by reviewing national and local news media, as well as fire service publications. A clipping service reads all U.S. daily newspapers and notifies NFPA’s Applied Research Division of major large-loss fires. The NFPA annual survey of the U.S. fire experience is an additional data source, although not the primary one. Web searches have proven useful in several cases where fire department and government reports have been released and published.

Once a fire has been identified, NFPA requests information about it from the applicable fire department or jurisdictional agency. We also contact federal agencies that have participated in investigations, as well as state fire marshals’ offices and military sources. The diversity and redundancy of these data sources enables NFPA to collect the most complete data available on large-loss fires. This report includes only fire incidents for which NFPA has official dollar-loss estimates; other fires with large losses might have occurred but are not included here because no official information has been reported to NFPA.

Due to a lack of confirmed dollar loss, several 2019 fires that might have resulted in property loss greater than $10 million were not included. These include fires at a Pennsylvania resort, a Pennsylvania refinery, a New York office building under renovation, a Kentucky liquor warehouse, a Nebraska chemical manufacturing facility, a New Jersey paper goods manufacturing plant, and an Oregon conflagration that destroyed 16 structures.

NFPA thanks the U.S. fire service for its contribution of data, without which this report would not be possible. In some cases, the fire department, forestry officials, or government officials were unable to contribute complete details because legal action is pending or ongoing, the incident was of a sensitive nature, or the size of the situation was overwhelming and reports had not yet been released. The authors also wish to thank Nancy Schwartz and the NFPA Applied Research group for their support for this study.

Stephen G. Badger, a fire data assistant with NFPA’s Research Division, is retired from the Quincy, Massachusetts, Fire department.

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

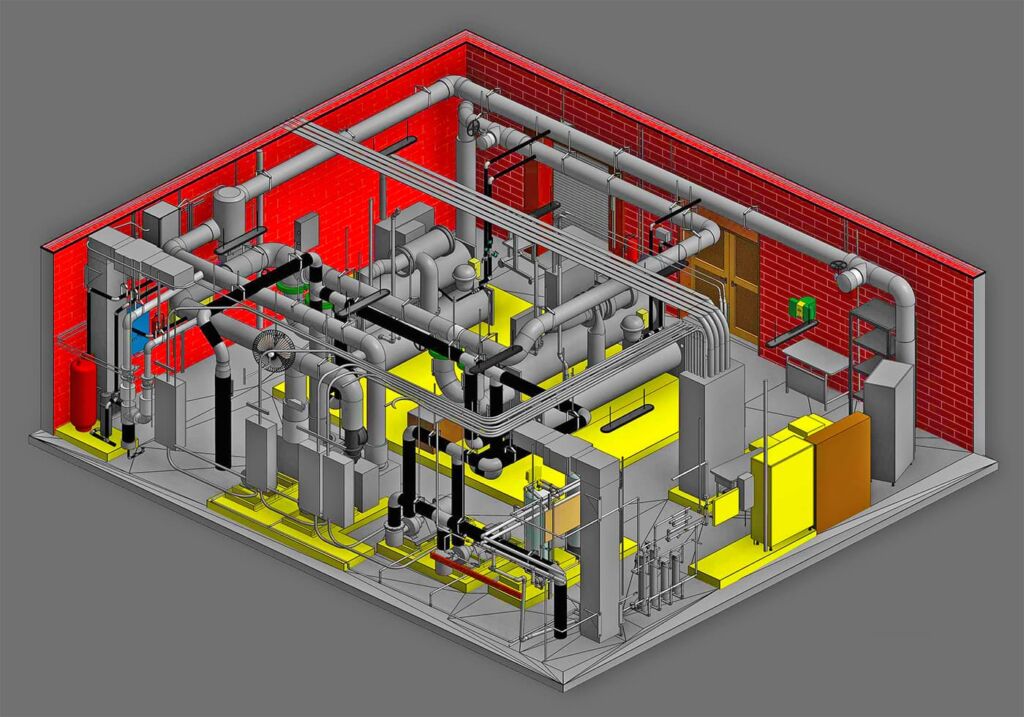

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.