Precision Fire Protection News

EMERGING: Drones for Fire Departments & Public Safety

Work has begun on the creation of a new standard, NFPA 2400, that promises to provide public safety agencies with much-needed direction on the use of drones for emergency response.

For two days in May, under the yellow-tinted lights of a hotel conference room in Dallas, a bevy of emergency responders, public safety officials, and industry experts gathered around a U-shaped table to discuss the intricacies of small flying robots. The questions were flying, too.

There were discussions about pilot training and standard operating procedures; required maintenance; drone decontamination; pre-flight checklists, risk assessments, and equipment specifications; and whether a small drone falling from the sky might land with enough force to kill a person. (Unlikely, but not impossible).

The group hashing out these details is the newly formed technical committee for NFPA 2400, Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (sUAS) Used for Public Safety Operations. Their aim is to create an industry standard on all things related to the use of public safety drones—a document they hope will not only be a roadmap for safety agencies, but perhaps even the catalyst to finally usher in the long-predicted age of aerial emergency response robotics.

For nearly a decade, unmanned aerial systems, or UAS in industry parlance, have been a fanciful dream for public safety agencies, with the promise of improving capabilities for everything from inspections to search and rescue and fire scene operations. More than a few prognosticators have used the term “game changer” to describe the devices, which for relatively little money can travel high in the sky or into tight or dangerous spaces to reveal valuable, and potentially lifesaving, information that no human safely could. The reality, however, has been decidedly less fantastic.

Until recently, the majority of departments that have explored developing UAS programs quickly thought better of it. Many were stymied by a mountain of unanswered questions or overwhelmed by the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) regulations, according to committee members I spoke to. Many of those departments that chose to remain blissfully unaware of the FAA rules moved forward only to find that their new hobby drones with limited battery life were about as much use on a fire scene as a Fisher-Price® fire truck.

Training Grounds More safety agencies across the country are getting serious about launching UAS programs. Top and bottom left, the Virginia Department of Emergency Management co-hosted a three-day conference in March to demonstrate UAS capabilities to numerous public safety agencies. Bottom right, members of the Austin (Texas) Fire Robotics Emergency Deployment team conduct flight training. Photographs: Top and bottom Left, Virginia Department of Emergency Management. Bottom right, Chris Wilkinson, Austin Fire Department

Within the last year, however, the dam holding back widespread UAS adoption has sprung significant leaks and appears poised to give out. FAA regulations have been streamlined and simplified, allowing almost any eager department to obtain a legal certificate to fly with minimal investment. Meanwhile, the cost of a reliable UAS suitable for public-safety operations has plummeted to $1,000 or less, even as technology and functionality have improved. As a result, public safety leaders across the country now see a realistic path to an aerial robotics program, and hundreds of agencies, from fire departments to police to emergency medical services, are pushing forward to launch one.

Charles Werner, the chair of the NFPA 2400 technical committee and a senior advisor at the Virginia Department of Emergency Management, told me that, in the past year, there has been “an exponential increase in the number of safety agencies moving to use UAS, and the applications are so numerous I can’t even count them on two hands.” As recently as 2015 there were maybe two agencies in Virginia even considering UAS programs, he said. Now, the Virginia Department of Emergency Management is working with about 45 separate state agencies on developing their own UAS programs, and the department has already trained nearly 140 UAS public safety pilots.

The increased activity isn’t unique to Virginia. “From my discussions with other chiefs around the country, it’s clear that UAS use is growing rapidly—I know a lot of departments that already have the technology and use it to great benefit,” said Keith Bryant, the longtime chief of the Oklahoma City Fire Department and a member of NFPA’s UAS committee. (He will relinquish his job in Oklahoma City soon to become the next U.S. Fire Administrator, the Trump Administration announced in May.)

But even as others have seen benefits from drones, Oklahoma City, like the vast majority of departments across the nation, doesn’t use them yet; with so little guidance available, Bryant has been hesitant to start a program, he told me. “I would feel a lot better about it for our department knowing that we are adhering to all the latest and applicable standards, laws, regulations, and so forth, which is why we’re taking a conservative approach,” said Bryant. “That’s why we have so much interest in the NFPA standard, to see what it says and what the requirements would be. I think that would give us some really good guidance on what do in terms of what equipment we need and how we are going to use it.”

According to a number of NFPA 2400 committee members, this lack of guidance may be the last major obstacle holding back the emergence of the aerial robotics age for emergency response. While some larger departments, such as the Austin (Texas) Fire Department and the Fire Department of New York, already have dedicated robotics teams with clearly defined operational procedures, dispatch protocols, maintenance programs, and data and privacy policies, the vast majority of departments simply don’t have the time, money, or expertise to write their own UAS regulations. Consequently, many departments like Oklahoma City are waiting on the sidelines, while others already have the robots but lack programs or policies on how to use them. “So many departments are just floundering in the wilderness on this,” said Gary Honold, NFPA’s northwest regional director.

The typical way many departments come to own a UAS, Honold told me, is by way of passionate firefighters who go to their chiefs with good intentions and persuade them to buy the department a drone. “Then they stare at it with no idea what to do,” Honold said with a laugh. “But they are ready to move on this. I have never seen more buzz about an NFPA standard than this one. Of all the meetings I go to it seems like 30 percent of the conversations are on UAS. I hear the questions all the time: ‘Is NFPA developing this? What’s going to be in it? Will it be out by the end of the year?’ All nine state fire marshals I work with can’t wait to see the standard.”

CREATING THE ROADMAP

NFPA 2400 stands out in a few ways, from the buzz to the holistic approach of its scope to the committee’s quicker-than-usual pace in writing it. Where some standards can take several years to develop, the need for guidance now, as well as NFPA’s efforts to streamline some administrative processes, could result in an accepted first draft of NFPA 2400 by year’s end, less than two years after the initial request to create the document. It is expected to go to the NFPA Standards Council for approval in December.

Instead of separate standards for UAS topics such as incident operations, professional qualifications, and the selection, care, and maintenance of the devices—as is the case for some standards, such as the fire apparatus documents—NFPA 2400 is all-incusive. The intent is to give public safety agencies all of the information they need in a single document for the sake of expediency and ease of use.

From fires to shooters Officials in York County, Virginia, use UAS during an active shooter exercise at a theme park. The drone can beam live aerial video of the incident area to the unified command post. Photograph: York County Fire and Life Safety

There is urgency to get the document out for a number of reasons, according to several NFPA 2400 committee members. Most obvious is the worry that a large number of public safety departments are currently using drones with no real policies or procedures in place, and perhaps even illegally without FAA approval, said Christopher Sadler, assistant chief of the technical services and special operations division at the York County (Virginia) Department of Fire and Life Safety. “I don’t think they are knowingly doing it illegally, it’s just that the information isn’t out there,” he said. “But it is a huge risk management and public perception issue.”

Aside from the obvious danger of a serious accident involving a drone that injures a responder or civilian, observers say, even the perception of recklessness could hinder the emerging drone movement before it fully takes off. The public is finally beginning to feel comfortable with public safety drones after years of resistance stemming mainly from privacy concerns. “All it takes is one screw-up for that to come back again and bite us,” Sadler said. “Having this NFPA standard helps assure our constituents and our elected officials that we are doing things the right way, and that there is now a roadmap to follow that gives departments something to work to meet.”

Many departments have moved forward with obtaining FAA approval to fly drones. Since the FAA’s new Part 107 rule on piloting commercial drones was issued in June 2016, about 43,000 Remote Pilot Certificates have been issued, according to FAA Administrator Michael Huerta. The certificates allow commercial drone operators (including public safety operators) to fly UAS with certain restrictions, such as flying under 400 feet and keeping the drone within the operator’s line of sight (see “The FAA Rules,” page 45). The process for obtaining the pilot license involves passing an FAA-administered test, a dramatic simplification from the expensive, months-long process previously required to obtain an FAA Certificate of Authorization, or COA, which was the only way public safety agencies could legally fly. It’s not clear what percentage of the new Part 107 pilot certificates have been given to public safety operators, but there’s little doubt it’s a growing stream.

Leaders in the public safety UAS movement, however, are quick to point out that obtaining an FAA pilot credential doesn’t mean a public agency is ready to take flight. There’s a lot more to it than passing a test and buying a drone, said Coitt Kessler, who leads the emergency robotics deployment team for the Austin Fire Department, one of the first departments in the nation to receive FAA permission to fly drones.

“The FAA did not design Part 107 specifically with public safety agencies in mind—we fit into 107, and we will make it work for us the same way we made COAs work for us,” Kessler told me. “But there are gaps for each of those. For instance, according to the FAA, you can self-certify your people—what does that mean? Do you really have a program in place to certify somebody? Do you have policies and procedures in place? Do you have training in place? My answer is I hope so. That’s why until now it’s been the Wild West—figuring out all of this without any real guidance is really hard.”

The FAA itself has said that the new licensing rule is nothing more than a blanket document that speaks broadly to all commercial pilots, that it is not tailored to the unique needs of any one group such as first responders. For those granular-level details, the administration is relying on organizations like NFPA to step up, said Wes Ryan, manager of the FAA’s advanced technology branch.

“We put in place a regulatory structure that needs to be filled in with industry expertise—we realize that the FAA can’t solve this on our own,” Ryan said during a recent panel discussion at the annual Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) conference in Dallas. “We need to collaborate closely with industry partners to bring about standards development that allows everyone to roll out this new technology in a controlled way.”

TAKING FLIGHT

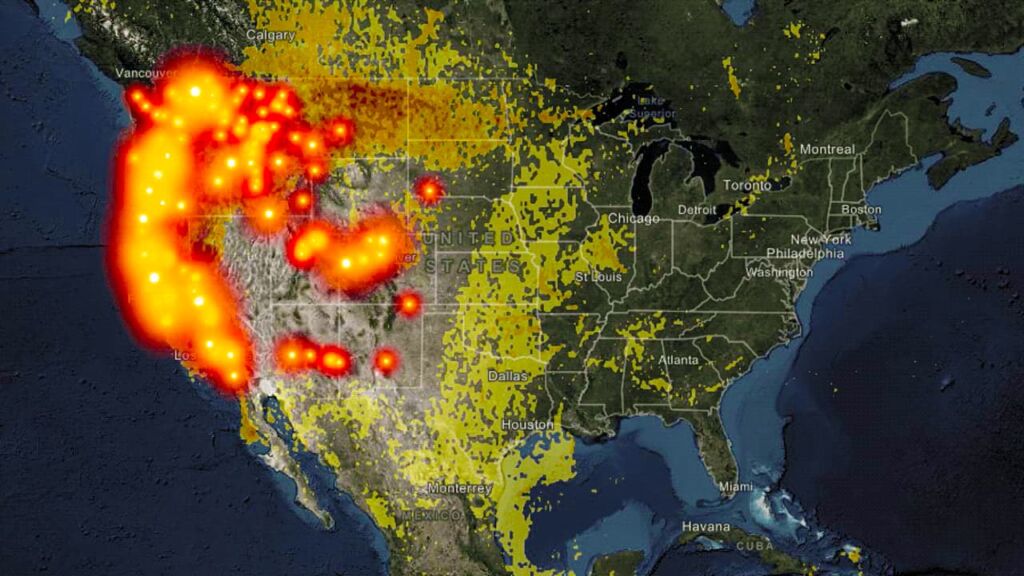

Even as guidance for public safety drones takes shape, there are already hundreds of examples of the robots successfully working in the field. Their numerous applications include searching for missing persons and locating disaster victims; inspecting hard-to-reach locations, such as the underside of bridges; scanning hundreds of square miles of forest for early signs of wildfire; securing buildings and rooftops ahead of parade or large public events; and allowing incident commanders to see important details of fire scenes.

Training + Deployment Bottom, members of the Fire Department of the City of New York train with a tethered drone that receives continuous power from the attached cord and can remain aloft indefinitely. Top, an image taken by a tethered drone of an apartment fire in New York City. Photograph: FDNY

The technology seems to be working in Austin, where over the last two years membership on the robotics team has grown from eight fire department employees to 21. And it has also been effective in New York City where, in March, the FDNY launched its first-ever drone at a fire incident in the Bronx. The tethered drones—which remain connected to a ground base via a small cord supplying power and therefore unlimited flight time—reportedly cost $85,000 apiece and are equipped with both regular and infrared cameras.

“That tool for a chief is just night and day from what it was not just 30 years ago when I started, but 15 years ago,” Daniel A. Nigro, the New York fire commissioner, told The New York Times. “Moving forward, technology like this is a terrific advantage for us and for fire departments around the country.”

York County, Virginia, has had a joint police and fire UAS team offering support to various county agencies and jurisdictions since November. The team has used drones to search for murder suspects and escaped convicts, conduct tornado damage assessments, provide intelligence during fire incident management, and even as part of its active shooter trainings, Sadler told me. Like any new venture, it’s been a learning experience, but the results have been overwhelmingly positive. The hardest part has actually been moving past old habits and convincing agencies to take advantage of the team’s new capabilities. “It’s been pretty interesting—half of the agencies are very excited about it and want our resources to come out and help them, and half say they don’t feel we can provide anything,” Sadler said.

In those cases, the UAS team usually convinces the jurisdiction to let it show up anyway so it can use the incident for training and to determine how well the concept is working. “One hundred percent of the time, after we show them our capabilities, they’ve completely changed their minds,” Sadler said.

A recent example involved a large marina fire in a neighboring jurisdiction. A state police helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft had already been deployed, but the state called in the UAS team, too. But when Sadler made contact with the local jurisdiction, the initial response was thanks but no thanks.

“I guess they were thinking that they already have millions of dollars in assets in the sky, so why do they need [a UAS team],” Sadler explained. “But it was one of those incidents where they allowed us to come out, prove our concept, and practice. Within five minutes of showing up, we were able to provide live video feeds to their emergency operations center, the state emergency operations center, the fire chief’s administration offices—they were absolutely blown away that we had those capabilities.”

When the fire marshal’s office caught wind of what was going on, they called Sadler over. “There were areas of the marina they couldn’t see by boat and definitely not by aircraft—the aircraft was flying at 500 feet—but we could come down 10 feet off the water and shoot video up inside the marina, and underneath the covered boat slips in the marina buildings—they couldn’t get that any other way,” he said. “Then we gave them an iPad that had our video feed on it so they could tell us exactly what they wanted us to zoom in on and take pictures and video for investigative and evidentiary purposes.”

Werner, the chair of the NFPA 2400 committee, told me that these examples are just a small fraction of the vast possibilities for drones. “UAS can impact every business model we have in public safety—they’re going to be ubiquitous,” he said, predicting that in five years 90 percent of public safety agencies will either have UAS capability or a way to gain UAS capabilities, and all of them will use NFPA 2400.

“Just like we went from the horse to the car, I think these things are going to be buzzing around in the sky everywhere,” he said. “It’s something we’re all going to be used to. It’s exciting to be here for the creation of this standard.” Sadler, who has seen what drones can do up close, has no doubts about any of that. He believes change in the fire service comes in cycles and that today’s fire service is poised for a great change.

“In the 1980s, HAZMAT was the big thing going on. In the 1990s it was technical rescue. In the 2000s it was integration of more EMS into the fire service. In the 2010s leading up to the 2020s, it’s been technology,” he said. “This will be the decade known for UAS.”

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

Experience

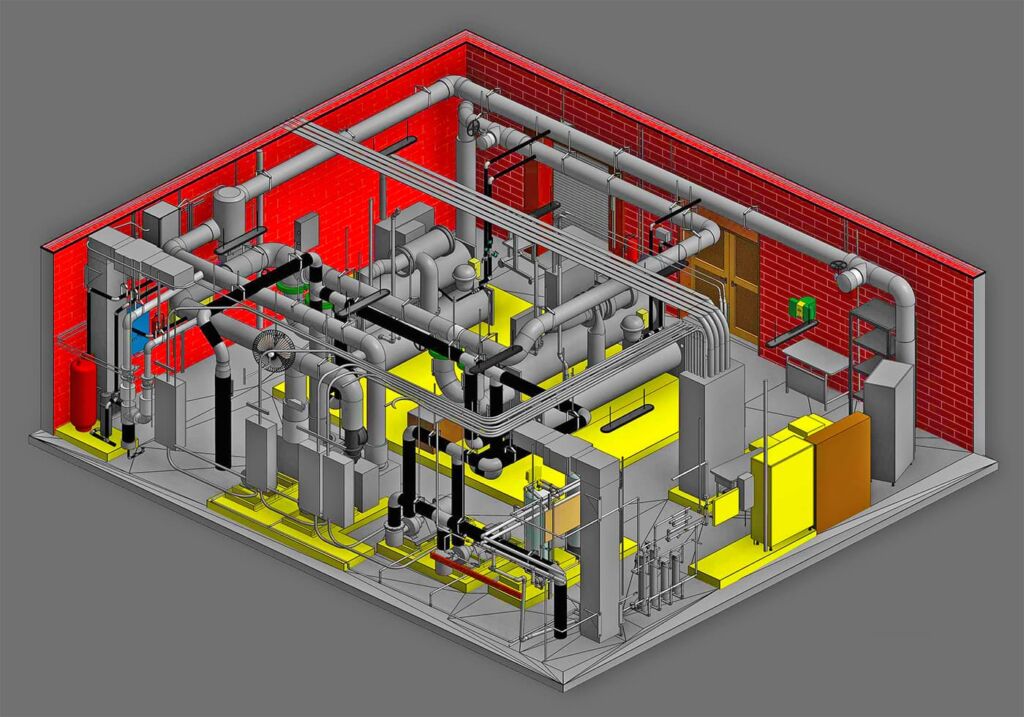

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

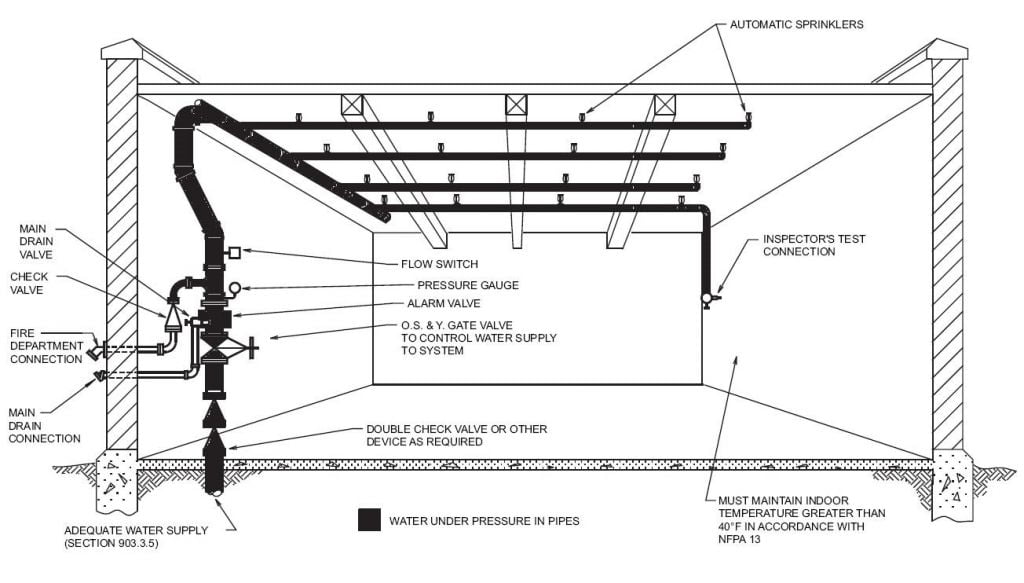

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.