Precision Fire Protection News

A Look Back: Health Care Occupancies

On the eve of a new requirement that all nursing homes in the U.S. be sprinklered, a look back at a half-century of progress—how we got here, the fires that shaped us, and the new challenges that continue to emerge

By Kathleen Robinson

By August 13 of this year, all new and existing nursing homes in the United States will be required to install automatic fire sprinklers, without waivers or exceptions, if they wish to continue to qualify for participation in the Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement program. The requirement was enacted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency that contracts with states to make sure nursing homes comply with federal standards.

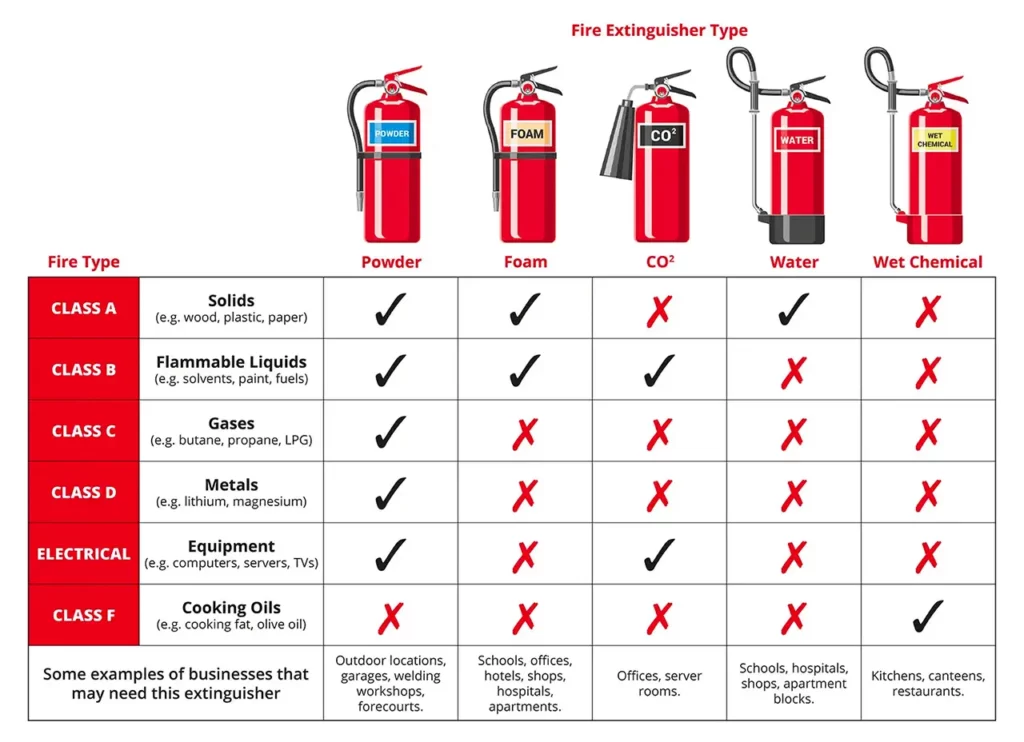

The requirement is a direct result of two deadly nursing home fires that occurred in 2003, as well as the culmination of a half-century of improvements in fire safety regulations aimed at reducing nursing home fires. From portable fire extinguishers to complete-coverage automatic sprinklers, fire and life safety code requirements have become stricter and more specific, and enforcement efforts more rigorous, making loss-of-life fires in these occupancies increasingly rare.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the fire at the Golden Age Nursing Home in Fitchville, Ohio, which killed 63 residents. It was the second-deadliest nursing home fire in U.S. history, behind only the Katie Jane Nursing Home fire that killed 72 people in Warrenton, Missouri, six years earlier, in 1957. Together, these fires represent a demarcation of sorts, between the fires that came before and those that came after. They also mark the start of a half-century of dramatic change in nursing home safety, driven by code requirements and the regulatory role of the federal government. Even so, work continues to try to minimize the impact of fires that threaten some of our most vulnerable citizens.

Tom Jaeger, president of Jaeger & Associates and a consultant to the nursing home industry, has nursing home fire information dating back to 1966, before the federal government started to enforce NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, in all nursing homes. Figures from 1966 to 1975 indicate there was an average of 15.8 deaths per year in multiple-death nursing home fires, Jaeger says, but in the most recent 10 years, from 2002 to 2011, there were 3.1 deaths per year. “That’s a reduction of more than 80 percent,” he says. “With the mandatory sprinkler requirement for all new and existing facilities, that number is likely to approach zero in a few years.”

Not that fires in nursing homes will necessarily disappear — as the facilities evolve, new fire safety challenges are emerging for both health and safety professionals. As the design of nursing homes becomes more residential and homelike than institutional, their fire protection needs will change. The provisions of NFPA 101 were substantially revised for the 2012 edition to address this, and will continue to be revised over time to protect residents as design concepts are further modified to address “resident first” environments. But as the CMS requirement illustrates, this is a new era for nursing home safety, one that looks very different than it did a half-century ago — or, in some cases, even a decade ago.

A step for Missouri

While the Golden Age fire may be closer to us by a handful of years, it was the Katie Jane fire that served as the impetus for the first serious effort to reform fire safety regulations in U.S. nursing homes.

The Katie Jane Nursing Home was a 65-year-old wood-frame, brick-clad building that had been turned into a 67-room nursing home with four wards in 1955. The two-and-a-half-story facility was home to 149 residents, many of whom were bedridden and some of whom were locked in their rooms. Fire safety precautions consisted solely of portable fire extinguishers, according to an NFPA fire investigation report from March 1957. There were no sprinklers, fire alarms, enclosed exit stairwells, outside fire escapes, or emergency lighting, and there were no fire drills or fire safety plan informing staff and residents how to respond in an emergency. There were no meaningful state regulations that required these features, and there was no federal oversight program that would have mandated such features.

On February 17, 1957, a fire began in an annex attached to the back of the home’s main building and smoldered for some time before a visitor discovered it around 2:30 p.m. During the five minutes it took the visitor to find a staff member and for the staffer to notify the fire department, 11 patients managed to escape. By the time firefighters arrived, five minutes later, the fire had grown out of control, and rescue efforts were futile. Seventy-seven residents made it out alive. Many of the victims died in their beds, or locked in their rooms. Appalled at the loss of life, Missouri Governor James T. Blair told the press that “the animals in the field take better care of their own.”

A month later, Blair signed legislation approving the Nursing Home Licensing Law, which tightened nursing home safety regulations, mandated inspections, and put tough penalties in place for facilities that did not comply. The law gave the Missouri Division of Health broad powers to establish and enforce minimum safety standards on convalescent homes and nursing homes throughout the state.

Nationally, similar standards had been on NFPA’s books for years. The Building Exits Code, the precursor to the Life Safety Code, recognized the special challenges associated with buildings where occupants could not easily exit or escape under their own power, such as facilities for the sick and infirm. In 1926, the draft version of the Building Exits Code had identified and developed the criteria now known as the “total concept” to emphasize the importance of fire-resistive construction, sprinkler systems, and the need for staff involvement in the safety of occupants.

Even so, fire safety remained a problem in U.S. hospitals and nursing homes. In 1929, a fire at the Cleveland Clinic killed 125. In 1949, St. Anthony Hospital in Effingham, Illinois, burned, killing 74. In 1950, a fire at Mercy Hospital in Davenport, Iowa, killed 41. In 1951, a fire at a convalescent home in Washington state killed 21. In 1952, 20 people died in a fire at the Cedar Grove nursing home in Missouri. In 1953, a nursing home fire in Florida killed 32.

Sprinklers delayed, with deadly consequences

While refinements were made to the Life Safety Code, including a separate section addressing the safety needs of hospitals, nursing homes, and residential custodial care homes, adoption and enforcement of the code by states and jurisdictions was inconsistent, and fires in nursing homes continued. Among them was the fire at the Golden Age Nursing Home.

Originally built in 1948 as a toy factory, the single-story building that housed Golden Age was eventually renovated into a nursing facility for 86 residents. Like Katie Jane, Golden Age had no sprinklers, fire detection system, manual fire alarms, emergency lighting, or written emergency procedures. It also did not have a water supply for firefighting. The extent of its fire safety features consisted of three portable fire extinguishers.

The fire started shortly after 4:45 a.m., when a series of small fires in the attic and walls merged into one larger blaze. A staff member discovered the fire and tried to call the fire department, but the fire had already burned through the phone line. A passing motorist made the call at 5 a.m. By the time firefighters arrived, 10 minutes later, the roof and one wing of the building were in flames and “it was impossible to enter the building,” wrote Ernest Juillerat, manager of NFPA’s Fire Record Department, in his report. Only 21 of the nursing home’s 84 residents made it out alive. Investigators later blamed the fire on faulty electrical wiring, noting that the building violated many provisions of the National Electrical Code® (NEC®).

In his report, Juillerat noted that Ohio had adopted regulations requiring nursing homes to install automatic sprinklers or a fire detection system and to comply with NEC requirements. The regulations were originally scheduled to take effect on February 1, 1961, but court actions brought by the Ohio State Federation of Licensed Nursing Homes were holding up their implementation when the Golden Age fire occurred.

In May 1964, U.S. Senate hearings on nursing home safety brought together the America Nursing Home Association, the National Council on Aging, the National Rehabilitation Commission, and NFPA, among others, who told the Special Committee on Aging that, although regulations for nursing homes, including fire safety regulations, were available, they were not uniformly adopted or, as in the case of Ohio, enacted. As a result, between 1964 and 1967 the U.S. Congress and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare worked towards a plan to incorporate by reference the Life Safety Code requirements that applied to nursing homes. In the late 1960s, federal rulemaking implementing the use of the Life Safety Code was approved and finalized, including provisions for the regulation and oversight of nursing homes. The act stated explicitly that as of January 1, 1970, skilled nursing facilities had to meet the provisions of the 1967 edition of the Life Safety Code that were applicable to nursing homes in order to continue to satisfy one of the Conditions of Participation (COP) to qualify for Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement.

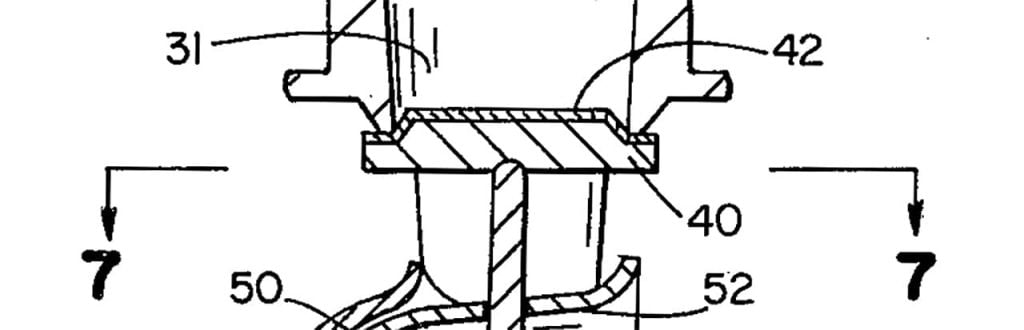

The substance of the 1967 edition of the Life Safety Code included many of the same concepts included in the 2012 code. These include two-hour separation requirements between the areas of a nursing home used for health care purposes and other areas; increased travel distances when automatic sprinklers are present; and limited conditions with respect to door locking. The code also required automatic sprinkler systems in new construction, except when fire-resistive construction was used and building-wide fire alarm systems were present.

Partly as a result of these provisions, which the federal government amended several times over the next three decades to comply with newer editions of the Life Safety Code, the number of large loss-of-life fires saw a steady decline. Between 1966 and 1975, there were 19 multiple-death fires in U.S. nursing homes, resulting in 158 deaths, according to data collected by Jaeger. From 1976 to 1985, three multiple-death fires killed 35 people. And from 1986 to 1995, four multiple-death fires killed 22 people.

“Prior to 1970, there was no national enforcement of fire and life safety in nursing homes,” says Jaeger. “It was all done by individual states. Once the Life Safety Code was adopted nationally for nursing homes in 1970, the losses started to drop rapidly, even though the Life Safety Code, the recognized standard of care, did not require sprinklers in all health care facilities. The national enforcement of the code was working, even though it did not mandate sprinklers.”

The last straw

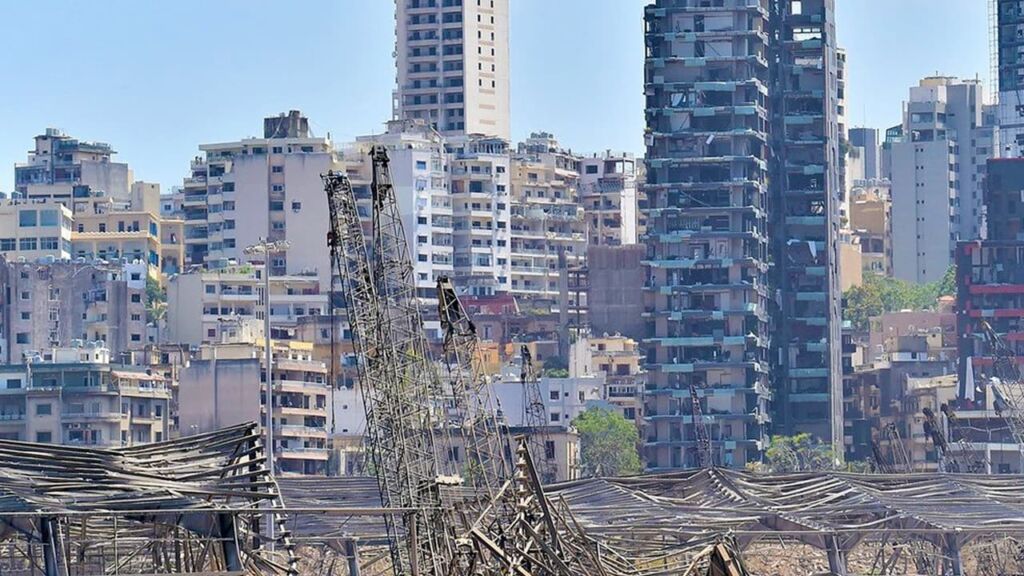

In 2003, however, in what can only be described as a setback, two deadly fires again focused attention on fire safety in nursing homes.

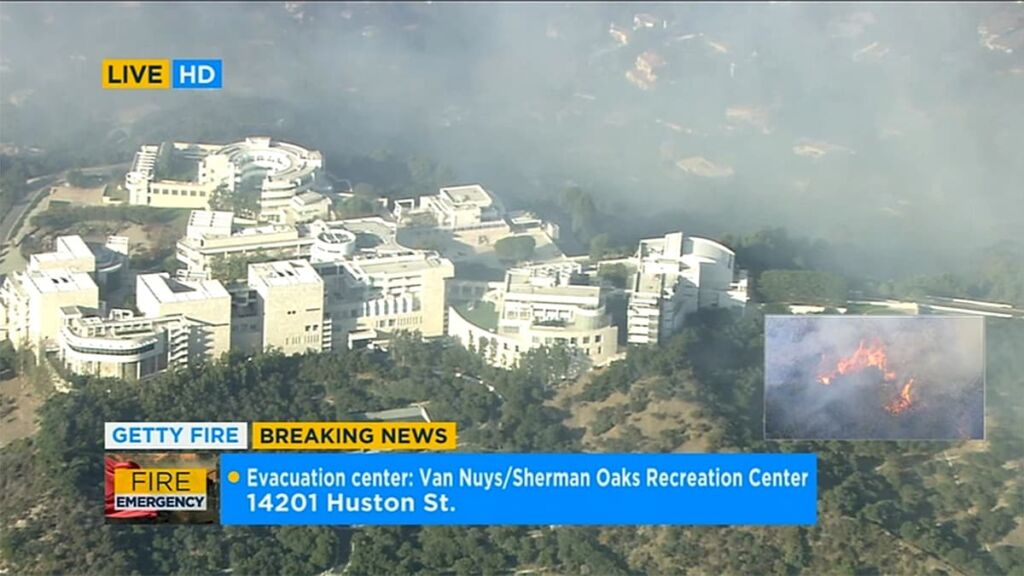

The first occurred in February at the Greenwood Health Center in Hartford, Connecticut, when a mentally disturbed patient set her bedding on fire with a cigarette lighter. According to NFPA’s investigation report, the fire spread to adjacent rooms and entered the building’s eaves before firefighters extinguished it. Ten residents died at the scene, and six more died later.

Unlike Golden Age or Katie Jane, the Greenwood Health Center largely complied with the state fire safety code. Interior walls of gypsum board provided a half-hour fire-resistance rating. Concrete block walls extending from the floor slab to the roof deck separated patient rooms, and the rooms’ solid-core wood doors, which opened directly onto the corridor, had positive latching hardware. Smoke barriers divided the facility into 11 smoke compartments, with corridor doors that closed automatically when the fire alarm system activated. The facility also had an emergency generator, a fire alarm system connected to the Hartford Fire Department, and smoke detectors in the corridors and common areas that were tested monthly by staff and twice a year by an outside contractor. A chemical extinguishing system in the kitchen protected the exhaust hood. It, too, was inspected and maintained by an outside contractor. In addition, a single automatic sprinkler protected the laundry chute between the first floor and the basement, and portable fire extinguishers had been installed throughout.

But an important fire safety feature was missing: complete-coverage automatic sprinklers, which were not required by the state. (A discrepancy in how the staff responded to the fire — a key component in the “total concept” safety idea — was also noted as a contributing factor in the outcome of the fire.)

Complete-coverage automatic sprinklers were also missing from the NHC Healthcare Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Because the facility was housed in a brick and steel structure built in the mid-1960s, it was required by the State Health Department to add sprinklers only if it was extensively renovated. The only sprinkler in the building was in the kitchen, over the grill. In September, a fire of unknown origin swept through the facility, killing 15. When asked by a reporter if sprinklers would have changed the outcome, Nashville Assistant Fire Chief Lee Bergeron said they “definitely would have made a difference.”

In 2004, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a study that looked at the entire oversight program dealing with nursing home fire safety and recommended, among other things, that the CMS explore the feasibility of requiring sprinklers in all nursing homes. A discussion was already underway with the NFPA Technical Committee about changing the Life Safety Code to require sprinklers in all existing nursing homes in the aftermath of the two fires in 2003, and NFPA’s review of the draft GAO report in May 2004 simply confirmed and reinforced the concept, says Robert Solomon, NFPA division manager for Building Fire Protection and Life Safety.

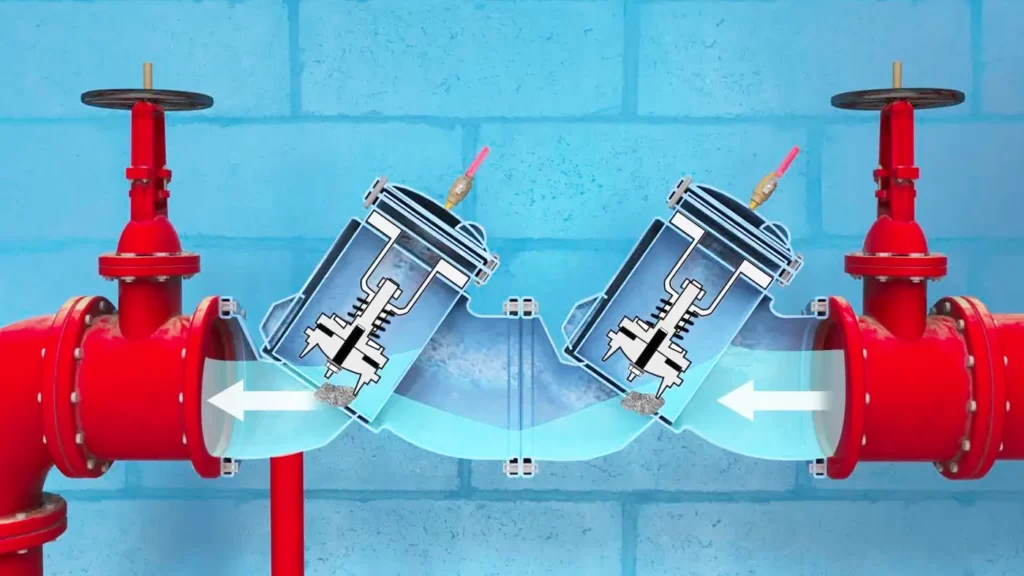

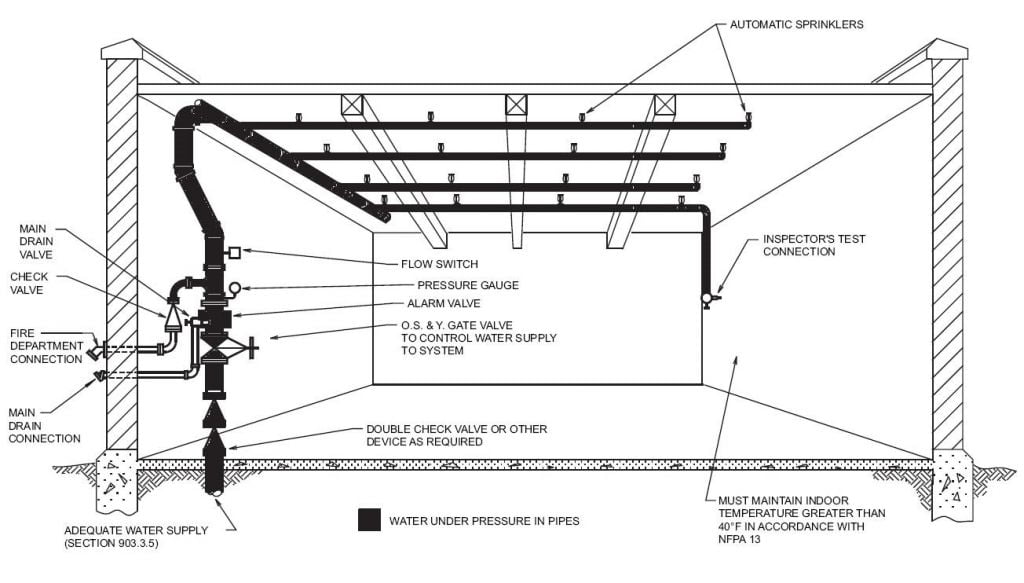

Knowing there would be pressure to improve fire safety in its facilities, the nursing home industry decided to become proactive, asking itself which fire protection systems would provide the best protection for the money. The answer was sprinklers. As a result, the industry submitted a proposal to the Life Safety Code committee and to CMS to mandate sprinklers in all existing nursing homes. (The 1991 edition of NFPA 101 had been revised to require all new health care occupancies, including nursing homes, to be protected with automatic sprinklers.) NFPA accepted the proposed revisions to the 2006 edition of the Life Safety Code, requiring the installation of automatic sprinklers in all existing nursing homes. CMS issued its final rule on August 13, 2008, requiring nursing homes across the United States to install automatic fire sprinklers, without waivers or exceptions, by August 13, 2013, if they wish to continue to qualify for participation in the Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement program. If they do not, they will face financial penalties or even loss of their ability to participate in their reimbursement program altogether.

Brave new sprinklered world

NFPA statistics for 2006–2010 showed that sprinklers were present in 70 percent of the reported fires in licensed nursing homes. Faced with nursing home fires large enough to activate an operational sprinkler system, sprinklers operated 89 percent of the time and operated effectively 87 percent of the time. Of the 13 percent of cases where there was not effective operation, roughly half were because the sprinklers were turned off before the fire began.

As many as 95 percent or more of U.S. nursing homes are already sprinklered, Jaeger says, meaning that other fire safety compliance options are now available, in part because fire safety must be balanced with other types of health and safety issues. For example, many nursing homes lock their doors to keep residents suffering from dementia from “eloping,” or wandering away from the facility unattended. This was not always necessary in the past, because the population of nursing homes was often more mentally acute than they are today. In fact, had they lived today, many would probably be in assisted living centers rather than nursing homes.

Some nursing homes also allow dispensers for hand sanitizers — a Class A flammable liquid — in hallways to prevent the spread of infections, a calculated risk/benefit in safety made possible by the presence of complete-coverage automatic sprinklers.

Another trend that may have an influence on fire risk is the move toward making facilities more residential and less institutional than they were in the past. Nursing homes may become smaller, Jaeger says, with 12 to 16 beds on a floor or ward, rather than the current 35. They might have fully functioning kitchens that the residents can use under staff supervision, and common gathering rooms may open to hallways. In short, nursing homes will become more like homes—and so will the attendant fire risks.

“As baby boomers age, they’ll demand this type of facility,” says Jaeger. “Since nursing homes might be the boomers’ final homes, they want them to be as comfortable as possible.”

With the design of U.S. nursing homes changing, we will begin to accept a little more fire risk, says Jaeger, much as we do in our own homes. Sprinklers can counterbalance both the changes in fire safety requirements and residential trappings by keeping any fire that may occur as small and circumscribed.

Despite his predictions, Jaeger is quick to add that the health care industry is changing rapidly, and that speculation on what it may look like decades down the road is just that. But he enjoys pointing out a cold fact: there has never been a multiple-death fire in a sprinklered health care occupancy in the United States. And that includes nursing homes.

PEOPLE We Protect

Our Distributors and Suppliers

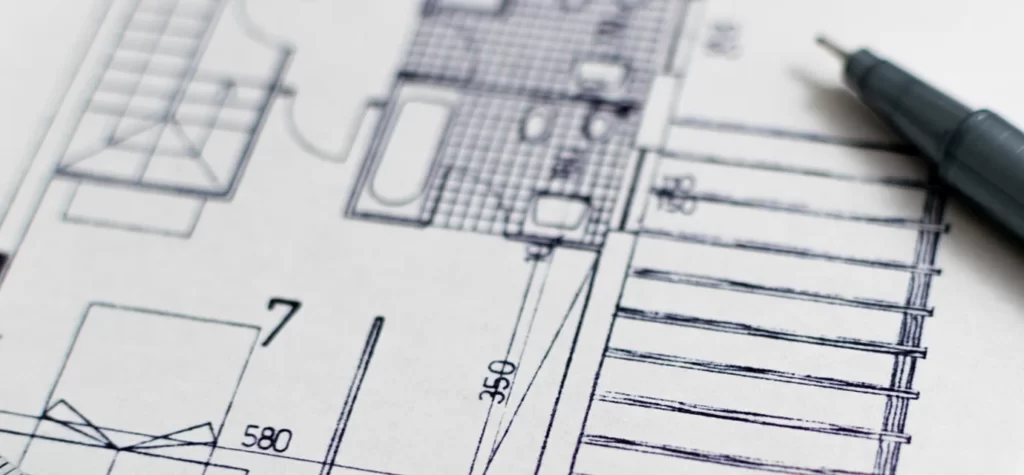

Experience

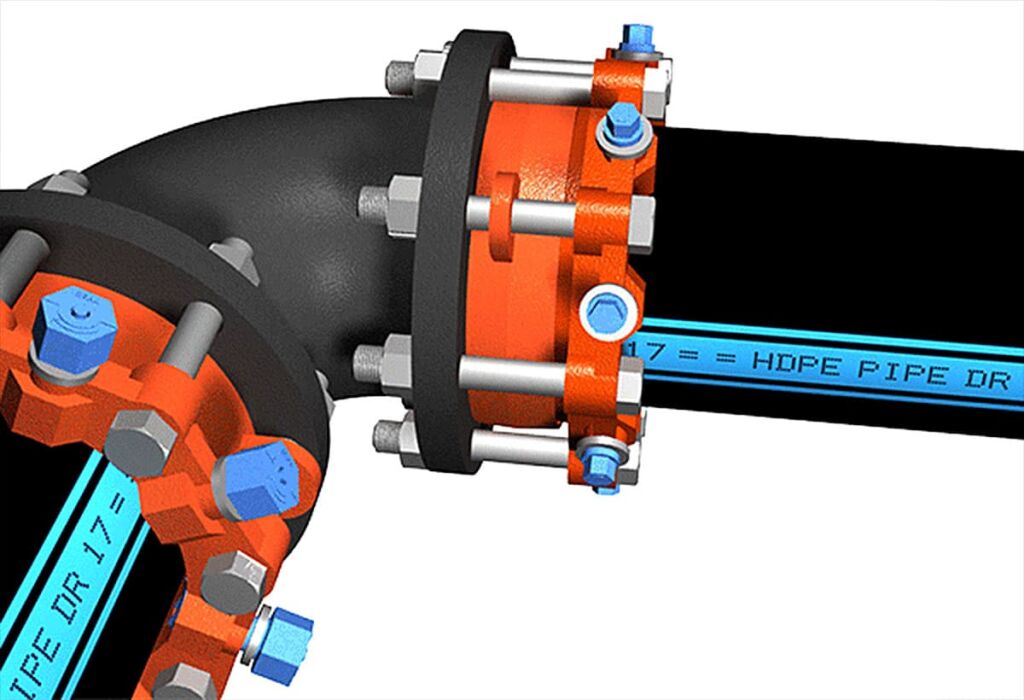

Our team started in the fire protection industry over 20 years ago. Since then we have grown into a statewide fire protection construction leader. Our team of project managers, engineers, designers, inspectors, installers, and technicians all share a passion for quality work and high standards. Precision Fire Protection understands the need to complete projects with integrity, safety, and precision!

Dedication

Our mission is to provide our customers with timely, high quality, affordable fire protection services that are guaranteed. We strive to achieve our client’s complete satisfaction. We are relentless in applying the highest ethical standards to ourselves and to our services and in communications with our customers. We aim to fulfill that mission in everything we do.

Precision

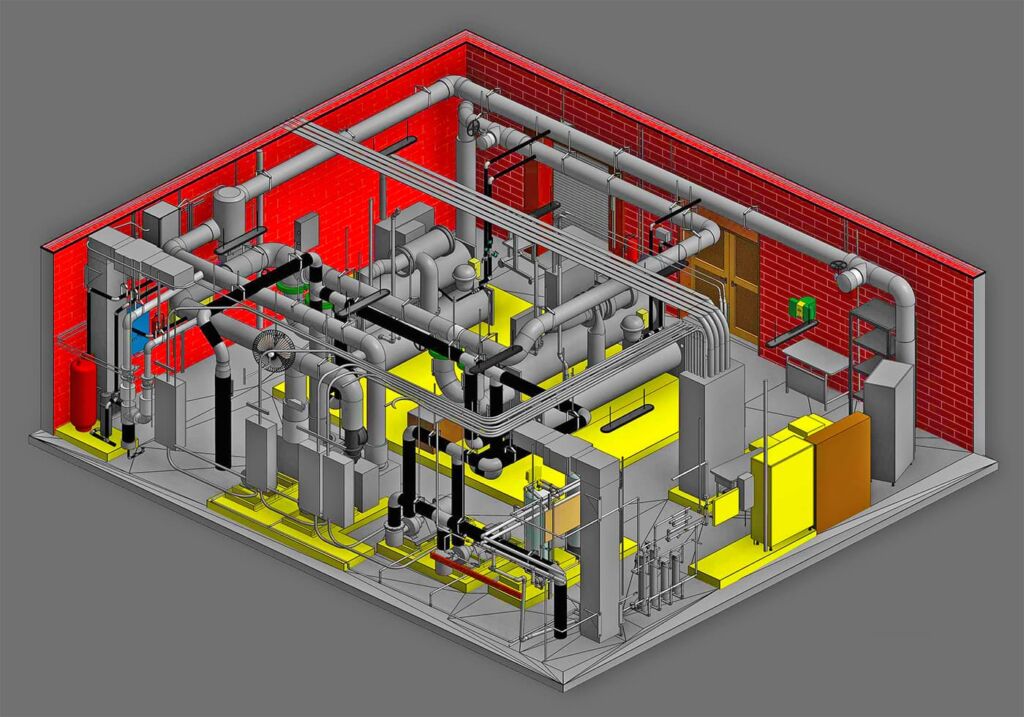

Precision Fire Protection keeps its team together, even when it's not. Just as vital as field personnel’s tools are, our project managers are equipped with the latest software to manage projects. Our project managers send dailies, RFIs, and plan revisions to the cloud so that everyone has access no matter where they are. Being connected is our way of ensuring every project goes smoothly.

Safety

Our team of multi-certified managers and supervisors are highly experienced in job safety. Our managers are OSHA certified to handle each project with care and sensitivity to every unique job site. By ensuring on-site safety on every project we work on throughout Southern California, Precision Fire Protection has developed positive relationships with our General Contractors.